The recent entry of online search specialist, Google into the spatial arena with Google Earth has caused a frenzy of activity, but what implications might this new generation technology have for mapping in the construction sector?

Over the past months we have explored the opportunities and challenges presented by changes in the nature of how detailed mapping products are made available to the professional map user. In so doing we have touched now and again on the tools and technologies, both embedded and emerging, that this user community has available. These are exciting and fast changing times in terms of the public perception of “mapping” technology and, by extension of, clients’ expectations. It would be naÈve to understate this impact so in this article we look at the new opportunities afforded to our users and some of the constraints and issues to be aware of when embracing them (as you surely will!).

Some of the more recent stories:

- Bentley Connects MicroStation to Google Earth Service

- Google purchases @Last software (SketchUp)

- Microsoft purchases GeoTango

- Skyline integrates 3D visualisation with GeoMedia

- ESRI licenses GeoMatrix toolkit to create ArcGlobe

- Swiss based Viewtec to launch TerrainView-Globe for 3D city models

- Autodesk MapGuide Open Source launched

- Mapping playing a major role in TV advertising for mobile telcos

- Mapping becoming integral to MSN, Yahoo, AOL, Ask, Amazon as well as Google

- Google requests shutdown of commercial Google hacks

- Oracle announces enterprise search tools

- Microsoft purchases Vexcel, makers of the UltraCam and FotoG software

Although MapQuest remains the leader in terms of users it is safe to say that the entry into the spatial arena of Google (not the first, but arguably the one with the most clout) has sparked both a wave of commercial and public relations activity from within the hereto fairly detached CAD/GIS domain and a recognition by the mainstream that there are undervalued and substantially untapped silos of spatial expertise, capability and content within the very same domain.

Thus such undersung CAD and 3D visualisation suites as SketchUp find themselves part of Google and GeoTango becomes submerged within the Microsoft behemoth. Does this sound the deathknell for much-loved tools, their re-emergence in different form and/or a real or perceived loss of the customer service values of the smaller companies? It depends who you believe of course but there seems little doubt that the major players are investing heavily in all manner of location and search tools and technologies.

Initially these applications were of most interest to the techie consumer and to online businesses seeking “simple” mapping components for their brochureware (think MultiMap’s “inline” services, StreetsAhead and so on) as the mapping available was no better than street level. A number of factors are changing this bringing these openly accessible services and the needs of the professional user into closer proximity; amongst which are the emergence of APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) and SDKs (Software Development Toolkits), the adoption of open standards and the improvement in content detail/resolution.

APIs in particular have enabled third parties to integrate with, connect to or extend their own applications (to varying degrees and with varying levels of success and sophistication) with the likes of Google. “Mashups” and “Hacks” are now widely embedded in blogs, educational and research sites, wikis, campaigning and NGO offerings reflecting ease of use, the importance of location and the “open”ness of the tools. Even Ordnance Survey is talking about offering an API in the future.

Support, amongst other things, for OGC’s Web Map Service and Web Feature specifications, XML type data structures, SOAP, AJAX and .net in particular has proved an inviting stimulus to new ways of extending awareness of 2D and 3D data sets to a wider audience. Much of this stimulus comes from the US where geographic data is perceived to be, or is actually, free and where the open source community thus has a ready made, if aged and inconsistent, medium scale content on which to build. Inevitably the resulting services are part of the global commons and the desire to exploit these for private, not-for-profit and commercial reasons have contributed in part to the re-ignition of the debate in the UK around the use and re-use of public sector information, including Ordnance Survey mapping.

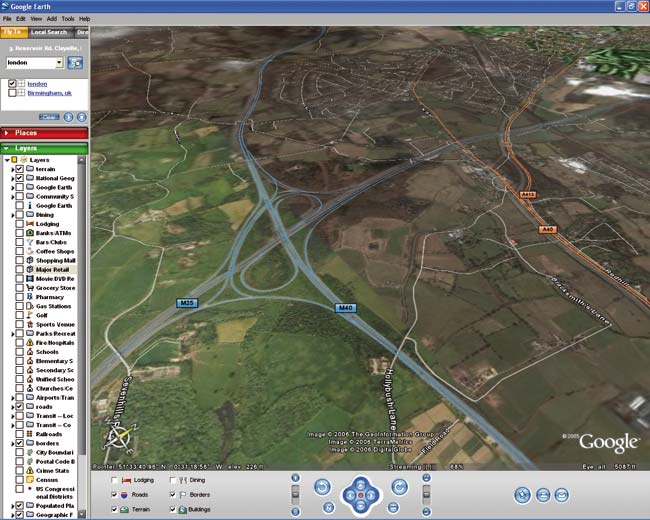

The decision of some content providers to license or sell detailed mapping and map-related products – usually aerial photography and satellite imagery – to the big mapping or geoportals is a stimulus of a different and disparate kind. By some this is seen as extreme short-termism by the vendors happy to have the revenue and optimistic that the license restrictions in the APIs will stick (see below) while others, equally optimistically, see this as the beginning of the end of what is regarded as expensive public sector information (about which a debate is raging in the broadsheets and online). Certainly it is both exciting and rewarding to enter a location and watch Google Earth zoom into recent detailed aerial photography for that location and to be able to either retrieve other data services over the top or even upload your own drawing files and generate a local 2.5D (which many insist on calling 3D) view of your site. Apocryphal stories also suggest that local authorities are even prepared to accept planning applications that use this approach and backdrop mapping.

Who’s doing it?

As the above indicates there has been a diverse range of mashups, hacks and third party development work undertaken, much of which has appeared in one form or another online (there are currently 366 mashups listed on www.googleearthhacks.com). The most visible user/developer group tend to be technical and often open source centric while as recent acquisitions suggest, larger interests are taking a more considered commercial approach.

Google Earth is not supposed to be used for commercial purposes or even in a business environment and it is arguable whether businesses that have Google Earth installed are creating for themselves a considerable liability.

It is this approach that does perhaps require the most attention as there a number of issues for users to be wary of, key amongst which is licensing. Google Earth is not supposed to be used for commercial purposes or even in a business environment and it is arguable whether businesses that have Google Earth installed are creating for themselves a considerable liability. Added to which the idea that taking licensed data from, for example, Ordnance Survey and publishing KML/KMZ files based on that on Google Earth (even if licensed the $360/seat to do so) breaches the data licence! And then it is important for businesses to be aware that while they can create and host content for online applications such as Google Earth and Yahoo! Maps, for the unwary uploading data into a Google Earth environment may in some cases mean that that data may be held in perpetuity on Google’s own servers with Google further retaining the right to search that data for their own purposes.

Many consumer technology plays entering the enterprise arena have become essential business tools – Skype and instant messaging being two obvious ones – while others have been banned/prohibited/discouraged owing to the impacts on productivity and performance of individuals and infrastructure and for the risks to which the enterprise was thus exposed. It appears that for the moment Google Earth is in both camps while those who assess the opportunity/risk balance, those who exploit the potential of the tools as they continue to emerge and those who would benefit commercially (the enterprise, the mashup artists and the content providers) agree secure operational frameworks.

It’s not all risk and gloom though, the times they are a changing; Google and Microsoft (and others) have moved from a position to date of organisations that collate, index and publish into the area of geographic data creation.

The likely emergence of a series of micro-payments based visualisation capabilities within consumer technology applications will enable those who develop a variety of geographic information including photo-realistic 3D models, dynamic analysis or development models (for flooding, terra-forming, urban planning), virtual worlds and much more to achieve wider audiences within and beyond the enterprise.

For traditional CAD and GIS silos these developments will be seen as potentially disruptive but from a broader perspective there are parallels with the renaissance of the “software as utility” application service provider model much-touted in the late 1990s. In this new world both the content and the functionality required to display and manipulate it are retrieved automatically from remote computers and paid for using a variety of models. Many commentators are of the view that the per seat licensing model is weaving its way into the history books to be replaced by a pay on demand/pay as you use model, a vision well served by these emerging geospatial tools and technologies and the reusable, extensible nature of the services they underpin.

This article was written by James Cutler, CEO at eMapSite, a platinum partner of Ordnance Survey and online mapping service to professional users