Early-phase engineering design is the least visible and least rewarded part of a civil engineering project, yet it can make or break a bid — and decide whether a concept ever advances to detailed design. AEC Magazine spoke to Adam Tank, co-founder of Transcend, and Chris Haney, STV’s Operating Group President for Water, about how automation changes that equation

Civil infrastructure design is entering a period of structural stress. Utilities, municipalities and public authorities are being asked to make long-horizon capital decisions under conditions of growing volatility: climate instability, regulatory churn, drought and flooding cycles, political scrutiny, energy price uncertainty, population growth and intensifying public accountability for ratepayer spending.

Yet the phase of a project that disproportionately determines its long-term cost, sustainability and political viability still begins in preliminary design, and it remains stubbornly manual, slow and under-resourced. For all the digital progress made downstream in BIM workflows, clash detection and construction coordination, early-stage infrastructure decision-making is still dominated by spreadsheets, siloed modelling tools, expert workshops and linear iteration.

In an environment where clients increasingly demand rapid answers to “what if” questions – what if demand doubles, what if discharge limits tighten, what if energy prices spike, what if potable reuse becomes mandatory – design teams are under pressure to explore multiple plausible futures quickly. For a growing number of firms, this is no longer a technical nice-to-have. It is becoming a strategic necessity.

Discover what’s new in technology for architecture, engineering and construction — read the latest edition of AEC Magazine

👉 Subscribe FREE here

This is also where design automation creates its greatest leverage. Not by drafting faster drawings or generating cleaner BIM models, but by compressing uncertainty at the front end of projects, scaling scenario exploration and turning preliminary design from a sunk-cost overhead into something closer to a decision-intelligence engine.

Traditional workflow

The conventional workflow for civil infrastructure optioneering typically begins with an early feasibility study and a series of meetings with senior engineers, process specialists and project managers gathering to interpret requirements, regulatory constraints and client objectives. Initial concepts are developed, filtered and iterated through a combination of spreadsheets, process-modelling software such as BioWin or GPS-X, and manual parametric tweaks.

For vertical and site context, this is supplemented with early-stage modelling in Revit and Civil 3D. But the real work happens outside those tools, in Excel, in meetings, and in the heads of experienced engineers. It is an intensely human, expertise-driven process and, for decades, the only economically viable way to explore complex infrastructure options under time and budget pressure.

What this workflow does not do well is scale. Each additional alternative carries a high marginal cost in time and labour. The economics of pursuit work mean that most firms converge on two or three formal alternatives simply because that is all they can afford to produce within a viable window. This constraint has nothing to do with a lack of technical imagination. It is a structural consequence of a labour-bound, manually iterated process.

It is in this context that New York-based STV’s experience becomes interesting, not because it was unusual, but precisely because it was typical.

Before adopting automation in its water and wastewater practice, STV’s preliminary design workflow looked much like this industry norm. As Chris Haney, STV’s Operating Group President for Water, described it, “We have a team huddle up understanding the requirements of the project, bring our experts together and have a series of focused conversations and work through some alternatives.”

The process was thorough, collaborative and heavily dependent on senior expertise. But it was also expensive in human terms, and much of the work never survived beyond the optioneering phase. As Haney put it bluntly, “a lot of that manpower gets wasted once the final preferred alternative is selected.”

The result is a structurally constrained exploration space. Clients are not choosing from an optimised or even systematically explored solution set. They are choosing from the small number of options that could be afforded under a manual, labour-intensive workflow.

This is not a moral failing. It is a tooling limitation. But it has profound implications for cost, risk and long-term performance.

Rapid is better

Until recently, this limitation was tolerable. Regulatory frameworks were relatively stable. Demand growth was predictable. Climate volatility was incremental rather than acute. Utilities could afford linear planning and single-track investment logic.

That world no longer exists

Public infrastructure owners are now routinely asked to commit billions of dollars under deep uncertainty. In the water sector alone, utilities face drought-driven demand spikes and potable reuse mandates, tightening discharge regulations, emerging contaminants such as PFAS, energy-intensive treatment technologies, political resistance to rate increases and public acceptance challenges, the so-called “yuck factor” in wastewater reuse.

These are not single-objective optimisation problems. They are multi-variable, policy-coupled and politically sensitive decision spaces.

In this environment, the ability to generate one good solution is no longer enough. Clients increasingly need engineering partners who can explore twenty plausible futures, explain the trade-space between them and defend why a particular pathway represents the least-regret option under uncertainty.

This is where automation begins to shift from productivity tool to strategic infrastructure.

STV as a reference case

STV is not a startup chasing novelty. It is a century-old infrastructure firm with more than 3,300 employees across over 65 offices, operating across transportation, buildings, water and aviation. It is, by temperament and history, a conservative engineering organisation that is now unlocking innovation through generative design.

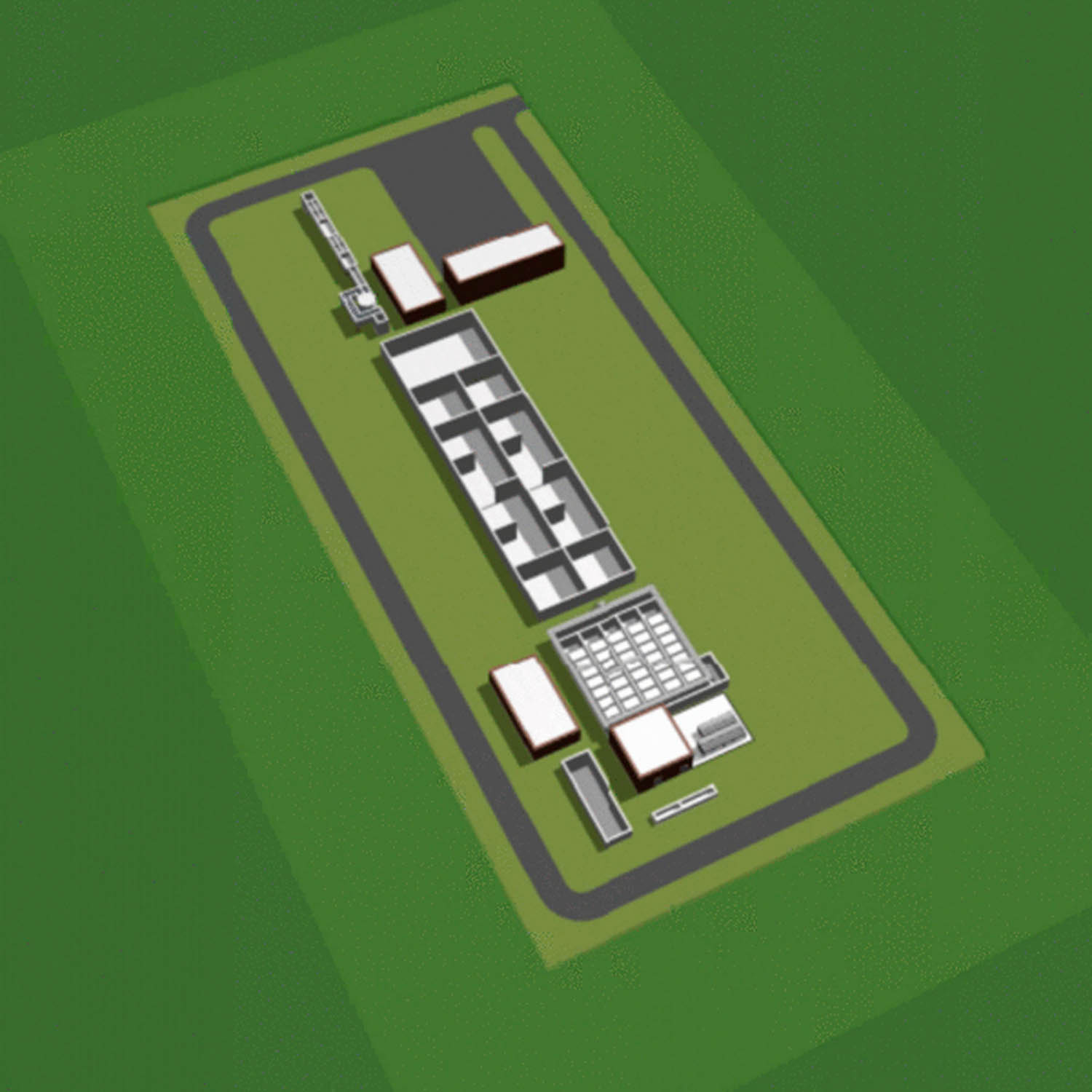

STV’s interest in Transcend’s Design Generator did not begin with blind faith. The firm subjected the platform to a reverse-engineering stress test, modelling a small wastewater plant that had already been designed, built and was in operation. The objective was simple, could the automated outputs approximate real-world engineering reality closely enough to be useful?

According to Haney, the results were “close enough” to build internal confidence. Only then did STV begin deploying the platform on real projects. “The real value proposition for us,” he said, “has been the opportunity to compress that time, be more efficient, and optimise our resources.”

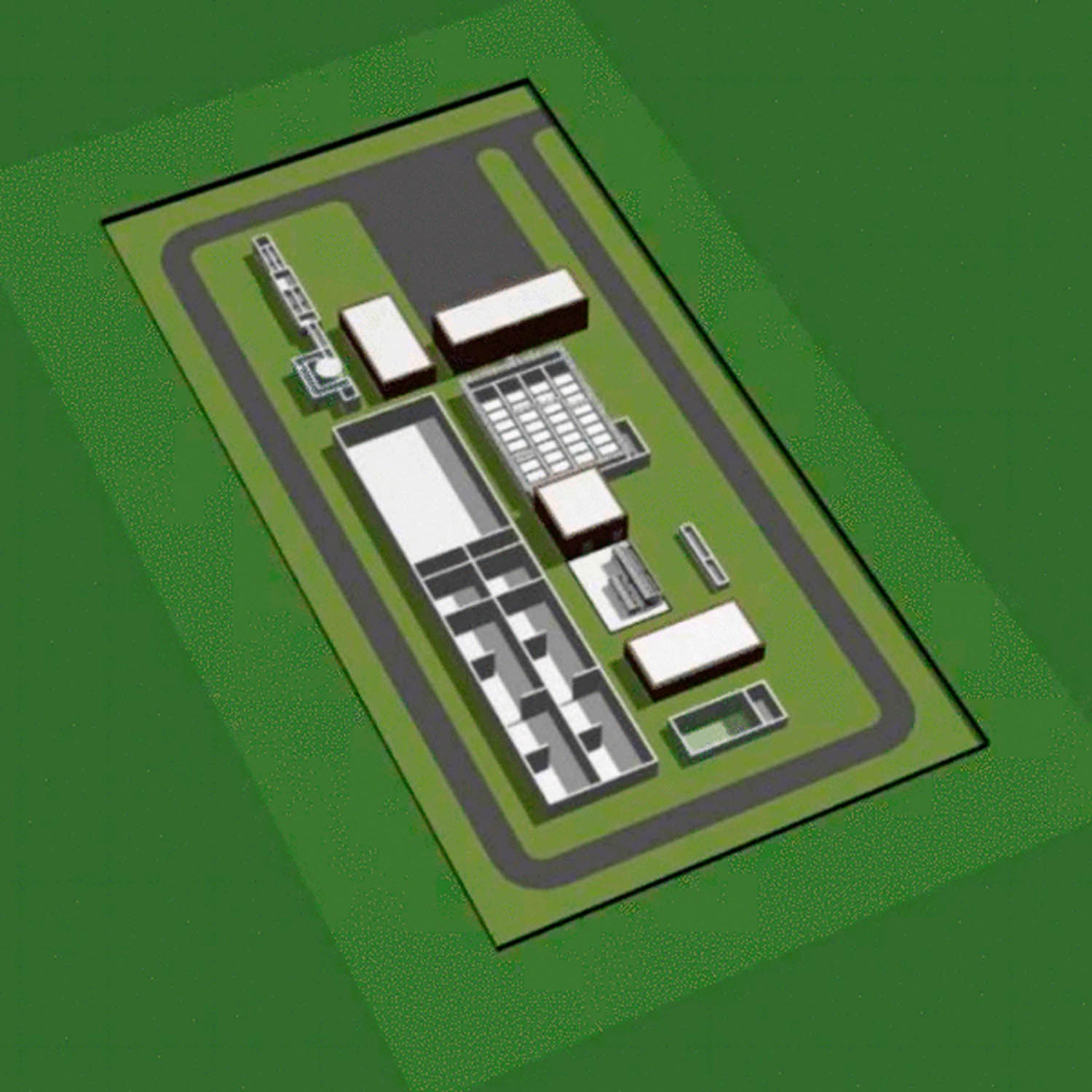

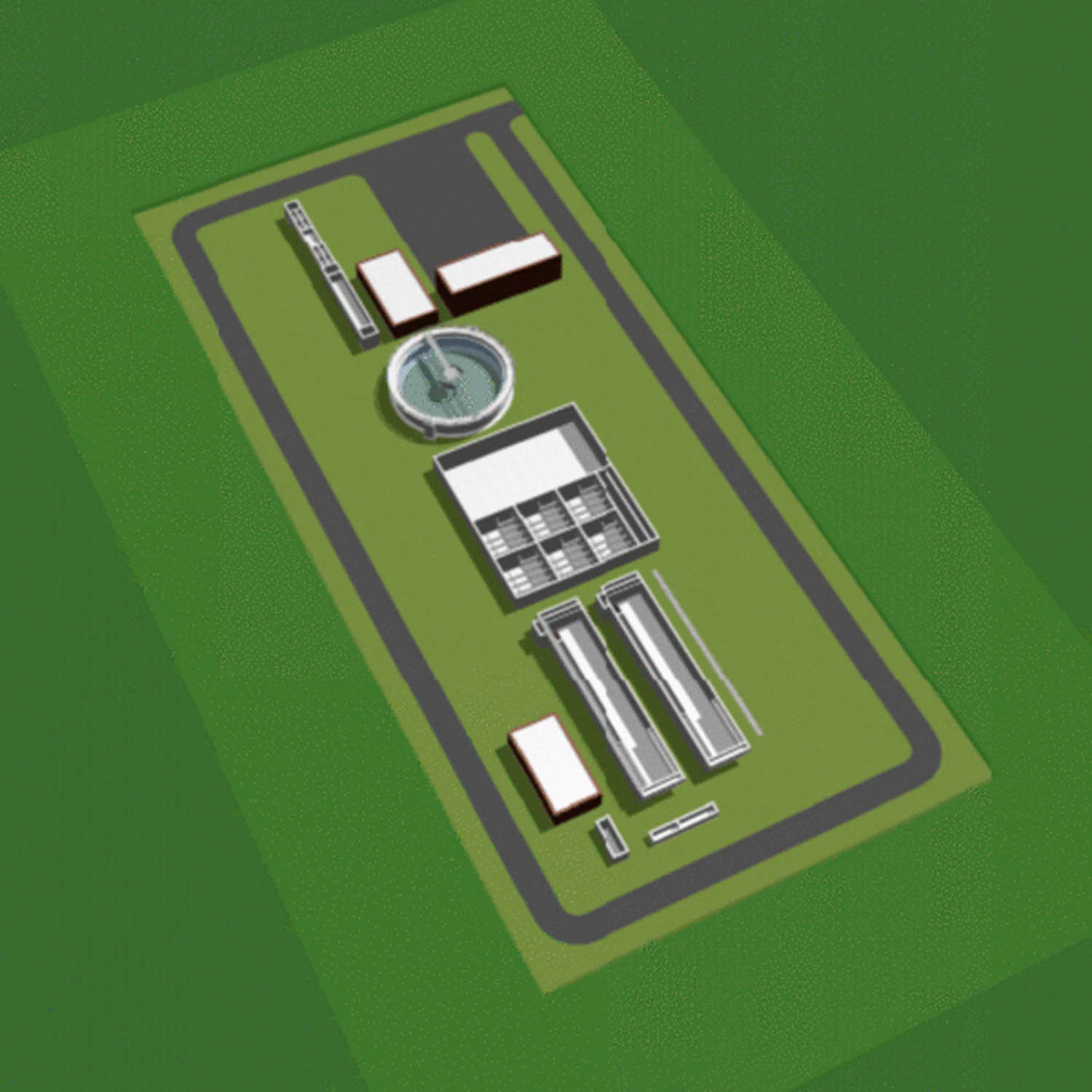

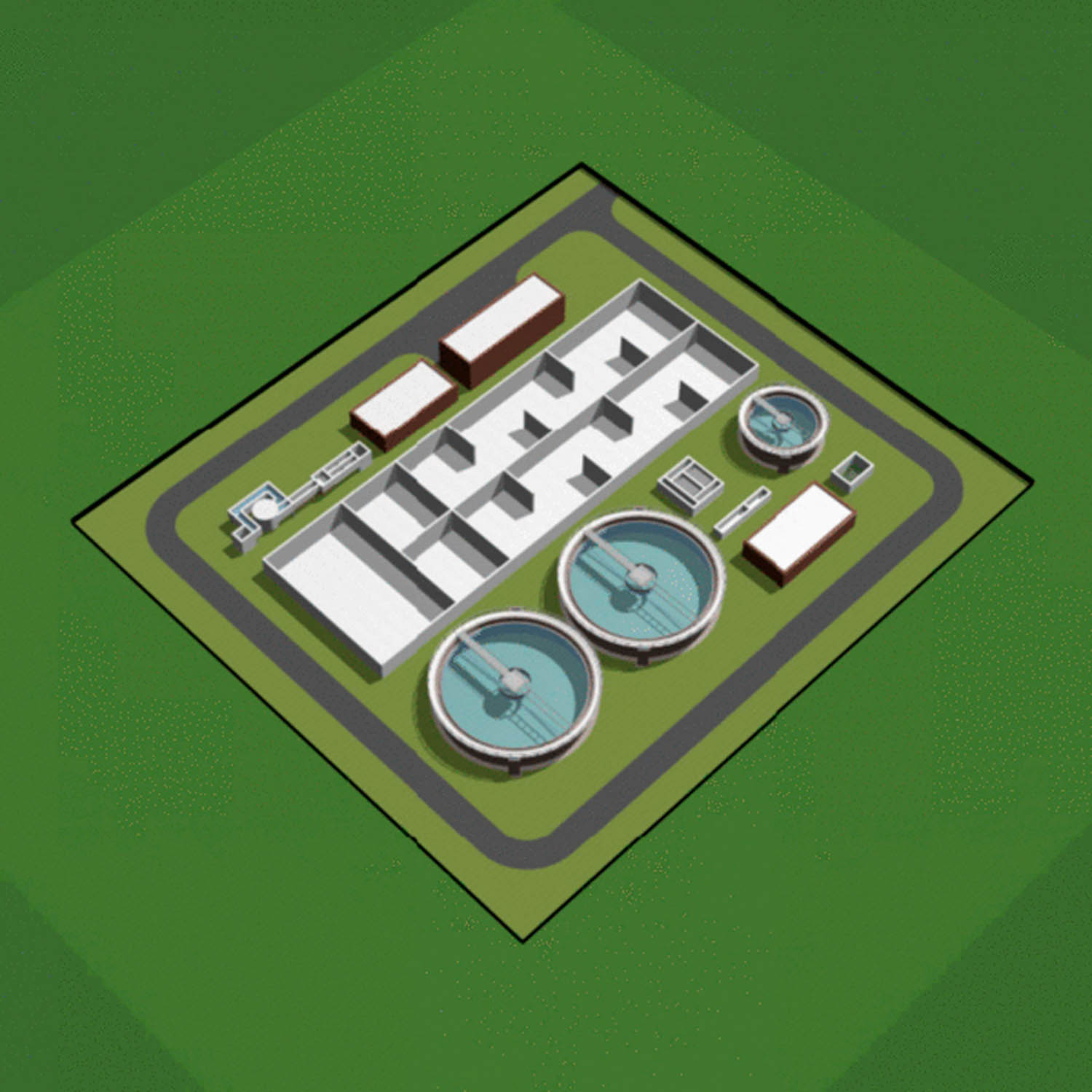

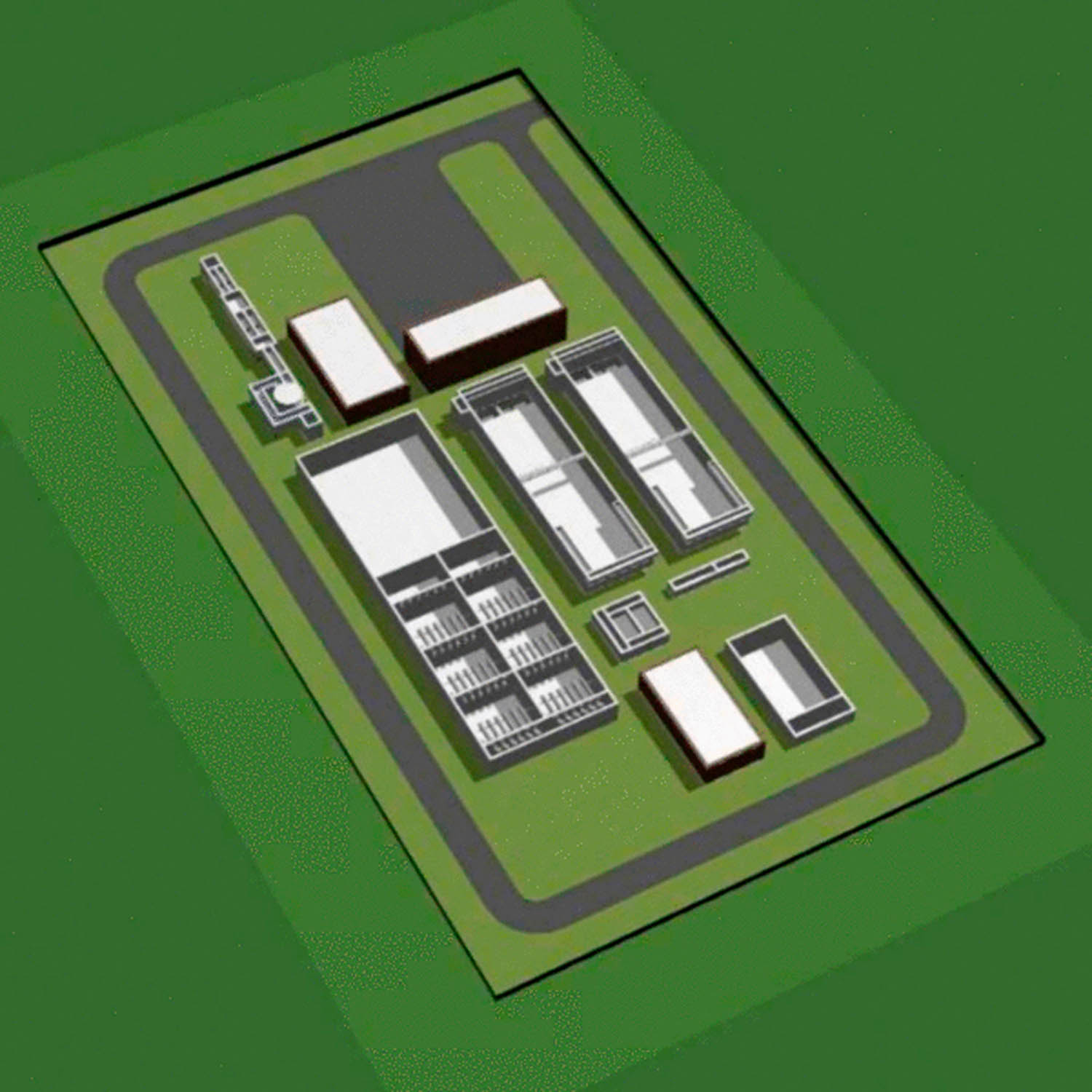

The inflection point came during a wastewater treatment project pursuit. Using the platform, STV evaluated multiple distinct alternatives, eventually narrowing the field to the top three options for discussion with the client. “We looked at exactly 25 alternatives over a period of maybe a month,” Haney recalled. That scale of exploration would have been economically impossible under its previous manual workflow.

The Transcend platform was never mentioned explicitly during the discussion with the client. What changed was the depth of diligence, the confidence of narrowing and the defensibility of the final options.

As Haney later reflected, the ability to bring a range of well-crafted solutions to address the client’s key issues proved that STV had “its ducks in a row.” The point is not that STV ultimately secured the job because of software. It is that automation materially altered how much uncertainty STV could burn down before committing to a preferred option.

Looking ahead

For Haney, this breadth of exploration is not another abstract technical benefit. It is a way of demonstrating diligence and public accountability, showing a utility client that the firm has “done their homework” and is acting as a better steward of ratepayer dollars, rather than advancing a narrow set of options shaped primarily by what was affordable to model.

That shift has also altered how STV thinks about competition and business development. Haney is explicit that in the current market, waiting for an RFP before proposing ideas is strategically weak. “If you wait for the RFP to bring ideas to the table, you’re not in a good position to win it,” he said. Automation allows the firm to be proactive, bringing well-formed alternatives into early planning conversations and using optioneering to advising clients on pathways they may not yet have considered. In that sense, generative optioneering is not just a design accelerator. It has become a front-end business instrument.

Crucially, STV does not treat automation as a substitute for engineering judgement. Haney consistently describes it as an “enhancement” to the ideation process rather than a replacement for it. The expert “huddle” still happens, but it now happens with more information, faster. Automated outputs, such as tank sizing, 3D layouts and water-quality reports, are treated as inputs to professional scepticism, not as authoritative answers. The leverage comes not from trusting the machine, but from giving experienced engineers a far larger and better-instrumented decision space to interrogate.

Conclusion

Automation in civil engineering is not about making engineers faster. It is about making infrastructure decision-making less blind, through rapid response, large-scale scenario exploration and the ability to compress uncertainty at the earliest and most consequential stage of a project. STV’s experience with generative optioneering is not interesting because it is exceptional, but because it is structurally inevitable. It shows what happens when a labour-bound industry collides with a tooling layer that finally allows early-stage decisions to be instrumented rather than improvised. It also shows how that tooling quietly reshapes organisational behaviour, pushing firms from reactive bidding toward proactive capital planning and front-end strategic engagement.

In practical terms, that shift turns sunk cost into strategic leverage, expands two viable options into twenty systematically explored ones, and repositions engineering firms from labour providers into decision partners. In a world of climate volatility, regulatory flux and capital scarcity, that capability is no longer optional. It is not even a competitive advantage. It is becoming the minimum viable standard for serious infrastructure planning.