Starting out in 1969, Hobs Reprographics has grown into one of the biggest independent digital printing companies in Britain. Three years ago it started offering 3D printing services and now produces models for some of the biggest architectural practices in the capital.

The rise of 3D printing in architectural model-making has been meteoric. Early adopter bureaux have grown swiftly across the UK as architects look to use fast and accurate models at every stage of design.

Compared to the space needed for a traditional model-making workshop, print bureaux housing 3D printers and post-processing facilities can squeeze into relatively small premises.

Using this small footprint to its benefit, Hobs Studio has moved closer to its main architectural client base. Its latest bureau straddles the north London suburbs of Clerkenwell and Islington, close to many of the Capital’s biggest architecture practices and construction companies.

All shapes and sizes

Unlike a model-maker’s workshop, the bureau has all the familiarity of a standard office, yet past the administration area lies a bank of 3D printers, all busy.

A lot of the models are straight prints of the 3D digital model for practical assessment, with few additional flourishes.

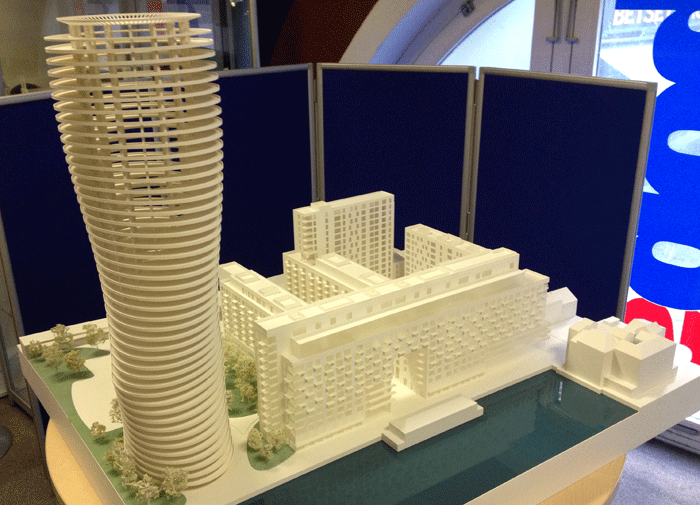

More complex presentation models include large cityscapes printed in miniature across connecting tiles, and whole schools produced in colour, with removable roofs exposing furnished rooms within.

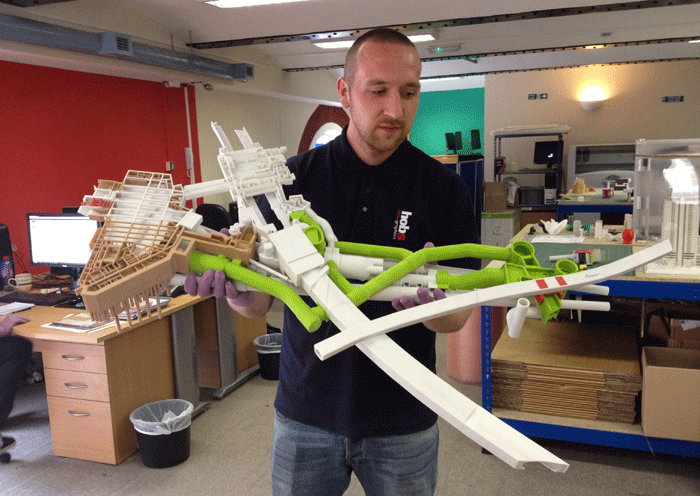

The construction industry comes to Hobs for models of rail stations, showing the various branches of the underground rail network that run underneath.

These can be produced in a matter of hours and in full colour on the bureau’s four 3D Systems Projet 660 printers and an older Projet 550, sometimes know as ‘ZCorp’ machines.

“Two years ago we had one 3D printer in a corner,” says Hobs Studio director Michelle Greeff. “I would fix the files then print them, take them out, deliver them, then run out and get more work.

“Now we’ve moved into here with six printers, and we’re the only one with the 3D Systems iPro 8000.”

The printer in question is the jewel in the company’s crown.

Sitting in its own temperature-controlled, glass-walled room, it can produce large stereolithography (SLA) models.

SLA gives the customer more model options, with a higher resolution finish. The parts are highly detailed and come with a refined surface finish, producing parts straight from a simple clean up, with a white or clear finish that is prized in architectural presentation models.

While initially appearing to be the more expensive process, the SLA is not that much more costly when materials can be reduced by, for example, deploying thinner walls, Ms Greeff says.

Quality and quantity

On the day of our visit, the iPro 8000 build tray has a mixture of parts for a globally-renowned architect mixed in with those for a luxury handbag designer, filling the build area to its maximum.

In an attempt to eke out every inch of productivity from the machine, Ms Greeff has invested heavily in the software.

The models are processed through Materialise’s e-Stage software that automatically generates the support material to position the model as it is being constructed layer-by-layer in the machine.

Normally, for some of the complex models, it could take half a day to place all the support correctly using earlier software, and a lot of manual skill.

“We got this machine because we wanted to start supplying our main accounts with SLA parts,” Ms Greeff explains.

“It’s not cheap, but it makes it perfect for us and the customer.”

Yet as Ms Greeff explains, customers still turn to the ‘ZCorp’ machines for faster build speeds and the option of colour.

Colour is used widely by construction and civil engineering clients to assess pipe systems, electrical lines, even entire underground train lines.

Looking at some of the models around the studio, it would be hard to imagine a pipe array having the same clarity if they were simply powder grey.

As Hobs’ clients expand their use of BIM they will now send models to be printed straight from a Revit file. This retains the colours, using an Autodesk FBX file, but it requires the right knowhow to transfer, clean-up and manipulate this data into a model ready for 3D printing.

3D environment

“Architectural models are by far the most difficult,” Ms Greeff says. Shrinking down a vast stadium model to 1:1000 of its size, for example, means that a lot of work must be done to maintain all the details.

A team of three Hobs staff work quietly, prepping the 3D models for print. They are all experts in print editing software Materialise Magics that allows them to resize, and sometimes restructure parts ready for printing.

Even experienced clients’ models require some tweaking, whether it is wall thicknesses, or fleshing out details.

“The software has got much better, and we’ve never turned a file away since we’ve been open. Although there was a file that took an entire week to fix — the remodelling of Victoria Underground Station,” explains Ms Greeff.

The Victoria Station model is now a prized achievement, with its many connecting tube lines and structures proving a tall order to remodel for printing.

Once the 3D model is fixed it can be used for some of the related 3D applications.

Hobs Studio now offers 3D visualisations, including virtual and augmented reality, which can work in conjunction with the 3D printed models, using them as overlays.

These can also be useful for the construction industry, detailing the process of erecting a tower, the movement paths of cranes and heavy vehicles on the site.

Since 2013 Hobs Studio has moved into 3D machine re-sales for architectural practices wanting to take the process in house, providing them with service contracts and consumables.

“We teach people how to make good files, says Ms Greeff. “We’ve learnt so much through the years, we know what the problems are, so we can throw in a bit extra TLC and help with the file side.”

And Hobs finds that some practices that have taken the technology in-house still require it to produce 3D models.

Already Ms Greeff is looking at more new additions to her 3D printer flock. Three years in, and only months into its new North London facilities, another change of office could be needed sooner rather than later.

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to AEC Magazine for FREE