There is a widespread industry move to adopt Building Information Modelling and intelligent 3D design. But, if the advantages are so clear, why stop with just the one building? Why not model the whole city? Martyn Day looks at the bigger picture.

News headlines in the early nineties occasionally covered the creation of ‘virtual cities’, where university academics or CAD developers would put together a 3D model of an existing city, or downtown area, because they had some funding or because, well, they just could. Typically ‘blocky’, these dumb models were primarily visual aids and were used to generate fly-by animations, or purely for the context of a major project. It was a time when the ‘virtual’ prefix could make a technology sound promising, but over time rarely delivered.

Scan forward ten years of computer innovation and there has been many advances in both the way we use technology and how technology impacts on our lives. With the popularity and amazing complexity of today’s 3D games, the growth of the internet and innovations such as Google Earth, we now frequently interact with and explore 3D worlds. Even photographs can be accurately geo-referenced via Global Positioning System (GPS) and shared online, or a house, road or city modelled in 3D in SketchUp, and uploaded. On the consumer level at least, the initial vision of virtual cities has been greatly expanded, with companies such as Google and Microsoft competing to produce nothing less than ‘Virtual Earths’.

But let us come back down to ground level. While consumers are finding many interesting uses for spatially referenced information, the professions of architecture, construction, infrastructure, civil engineering, urban and town planning, to name but a few, have a geo-spatial component to nearly every project. With every firm modelling the surrounding areas of their next project – reinventing the wheel — wouldn’t there be benefits to having access to an accurate master city model? With the trend of adding valuable information to 3D models and their components, couldn’t a master model of these intelligent projects, offer considerably more than just the dumb geometry vision of the past or the spatial-wiki of Google Earth?

The business opportunity offered by such a digital city may not be totally obvious. Consider the management of key infrastructure projects such as waste, water, energy and transport. The drive towards achieving sustainable, yet desirable and economically successful cities has only just begun. In China, for example, whole cities are being planned and constructed. Dongtan eco-city required a city model to test urban strategies for its infrastructure and there are plans in place to connect the city model to a smart metering system to capture valuable energy usage information streams – a digital dashboard for the city. For cities with aging infrastructure and a scarcity of greenfield sites, there is a need to capture what is already built to explore new projects, better maintain existing investments and renew worn-out utilities. A digital city could be a valuable resource for every stage of development, from cradle to grave — or with a sustainable mindset, cradle to cradle.

However, while the engineering and planning may concern us, many times the initial budget and justification comes from cities’ economic development agencies. This is because these agencies usually have the budget to attract new businesses into their cities. Making a digital city is a cost efficient way of marketing, as opposed to creating a couple of cool fly-overs and getting a little airtime on television. People are able to visit the virtual model and it can be brought to life by many different departments to capture and improve planning and construction.

Convergence of data

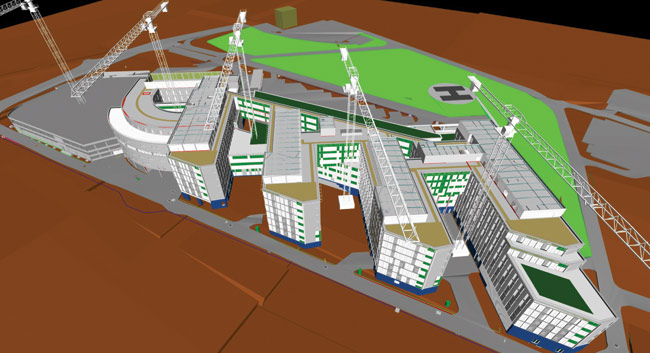

Digital cities can be created using Autodesk LandXplorer Studio Professional. The software is designed to handle terabytes of 2D and 3D geodata sets for the visualisation and exploration of digital terrain models and terrain textures. High quality renders can be generated in real time and the models can be interrogated with vector and analysis tools, such as distance queries and land analysis.

In addition to GIS and 3D formats, LandXplorer Studio Professional supports CityGML, which is the industry standard for exchanging city model data. A popular output has been the creation of 3D city models for Google Earth, as well as for marketing, and serious uses such as urban and town planning.

Price: €8,950 (single seat)

€21,995 (server edition for 1-8 cores)

To enable the construction of a digital city all one needs is data, and here, all areas of building and infrastructure design are moving to create 3D models with rich layers of metadata, allowing advanced analysis, simulation, quantities take off and estimates energy usage across the lifecycle. In the GIS world, what started off as just a 2D process, now encompasses the inclusion of real-world information, together with 3D topography, built on extendable databases that can manage terabytes of data. Visualisation technology has also driven the use of 3D in games, films and TV. With new techniques we can render huge models better and faster.

Undoubtedly we have seen Moore’s law play out in workstation technology with much faster 64-bit processors now accessing vast amounts of RAM, together with stunning advances in computer graphics power, capable of rendering millions of textured polygons. We are also on the cusp of seeing ‘cloud’ server farms with thousands of processors being able to process terabytes and petabytes of data, to be served-up in real time down the internet. In short, all the technology is now in place to build complex, intelligent 3D digital cities.

BIM on a city scale

Doug Eberhard is the senior director and industry evangelist for Autodesk’s ‘Digital Cities’ vision. He explains: “Last year Autodesk acquired 3D Geo, a Germany-based infrastructure and urban planning developer, with its LandXplorer Studio Professional software that enables data aggregation and modelling on a macro or ‘city’ scale. Looking at the design landscape, the use of information modelling is bringing all the essential processes together — we are moving from file-based to model-based collaboration, which enables Building Information Management (BIM) on a city scale. LandXplorer Studio Professional can import spatially referenced 2D and 3D data from a huge array of systems and common formats and display this in a visually rich environment, in real time.

“This is not like Google Earth as customers want accurate information and care about what is below, on, and above the ground. You have to be able to factor in utilities, networks, roads, rail, and buildings and then be able to analyse, simulate, and collaborate on that data. In the past, this may have been carried out for each individual project, covering a very limited area of a city. With a digital city you can look at ten or more different projects simultaneously, in a broader context. While it may be prohibitively expensive to create a city model for one project, pool three, four, or ten or more projects together and it becomes great value. The more you use it, the higher the return. Cities live and breathe, they are always changing and being renewed. Here, a city model can be an invaluable tool to capture and store what was, accurately document what is, and test what will be.”

However, to date, all the essential data needed to create the model sits in multiple departments and companies, in silos, where one department may not talk to another or share any information. With the introduction of many joint public/private partnerships, sometimes this information is also held outside local governments’ control. So there is never one model, just lots of data sources in different domains, frequently reinventing the wheel. Mr Eberhard suggests things are changing: “There is a demand for more transparency and accountability. Everyone agrees that if you can bring all this data and geometric information into a spatially referenced database and share it, there are massive benefits. The model can then be used for traffic simulation, energy analysis, hydrology, slope analysis, or flood and pollution simulation. Sensors can be placed in the actual buildings or bridges and accessed from within the model. Or if designing a convention centre, the capacity of surrounding hotels and access to transport can be quickly identified. Digital cities are all about improving decision making on a macro level.”

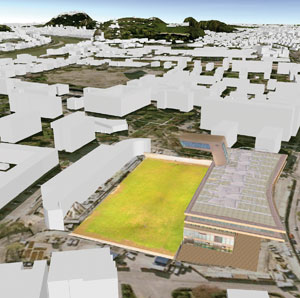

But before anyone can even think of building a digital city, the benefit has to be sold to all the various stakeholders, the local government departments and private firms in order to get their buy-in. “In my experience, a ‘Digital Cities’ pilot provides a great forum for all the departments to come together and have a positive discussion as to how they can benefit from sharing their data,” says Mr Eberhard. “Usually, the various departments are digitally well managed and it is a simple case of pulling the data sets together in a co-ordinated way. You don’t need to start with a perfect map of the city – not all the buildings have to be perfect and textured, that can be left until version two or three. A large percentage of the below-ground data may only be 2D but it is still very usable for a first attempt. With LandXplorer Studio Professional it is possible to take existing co-ordinated data and build a digital city in an afternoon. From the parcel data you can give all buildings an arbitrary height and have an instant 3D model, but many local governments hold building height data in a database and this can be automatically added too. Later, using LiDAR (Light Detection And Ranging) and photogrammetry, exact roof pitches, overhangs and textures can be added. For signature buildings, most customers use 3ds Max to model stadiums, churches and places of historical importance.”

Autodesk’s digital cities

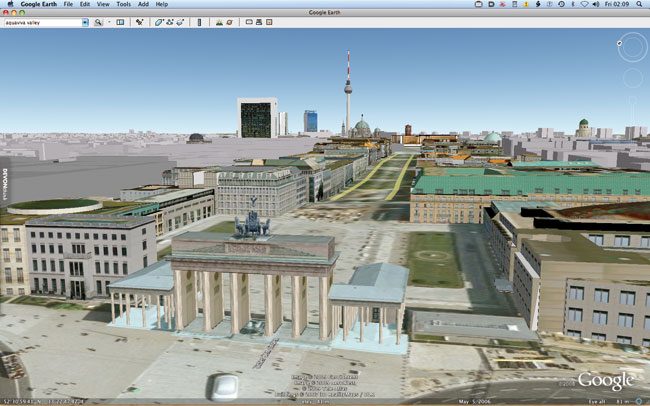

Autodesk has a number of customer cities around the world: Salzburg in Austria, Incheon in South Korea, Berlin (pictured in the main image, pages 16-17) and Dresden in Germany as well as Vancouver in Canada. Autodesk is also in negotiations to develop other digital cities around the globe.

Salzburg is the fourth largest city in Austria and a UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation) world heritage site. The 2,000-year-old city is under pressure to expand while constrained by valuable green belt land. A research pilot project was agreed in conjunction with the Centre for Geomatics at Salzburg University, to explore considerate urban design technology for citizens, businesses and key government agencies.

Autodesk’s Mr Eberhard recalls: “The first step was sitting down with all the various departments, public works, economic development, city management, financial, and operations people, to see how they were currently working, what was missing, and how it could be enabled though the re-use of models. It was literally taking years to get planning approvals through the system. The digital city project established a workflow to enable the development of standards for the urban planning process. There is talk of getting architects to post proposed buildings to an online model, managed by the city.”

In the case of Berlin, the project was initiated by the Senate Department of Economics and the Senate Department of Urban Development. The digital city model forms part of the ‘Investor Information System’, hosted at the Berlin Business Location Center, and acts as the platform for ongoing projects in city planning at the architecture working group of the Senate Department of Urban Development.

There are already 500,000 individually texture-mapped buildings with all the transportation networks. Some of the below-ground data is in less detail such as 2D lines from GIS systems, however, an immediate benefit of the project can be seen in Google Earth, with all the buildings being available for view online. (Simply visit Berlin with the 3D building tag switched on).

Vancouver is a city with slightly different limitations — it is surrounded by water. The city is addressing sustainability issues and has a strong EcoDensity Charter in place, which makes environmental sustainability a primary goal in all city planning decisions. The city is also undergoing considerable regeneration as it prepares for the Winter Olympics in 2010.

To support several planning activities, Vancouver began a digital city project ten years ago to model the downtown districts. This evolved into the adoption of geospatial mapping and the creation of Vanmap — a web-based map server that provides multi-layer CAD and GIS data for citizens and provides richer content for internal departments.

Vancouver has been in the practice of sharing and converging its data for many years, and this is becoming increasingly more 3D. The city is producing a fully accurate, texture-mapped digital city of the entire greater region, which will include all utilities, transportation and operational information. Again, the city will look to share the model with all stakeholders.

Appetite for construction

According to Mr Eberhard, typical budgets for digital cities range from US$50,000 to US$300,000. However, there was one exceptional project that had a budget of no less than US$16 million in the Middle East. Mr Eberhard explains: “There has been a big shift in the past couple of years with aerial image providers such as Digitalglobe (www.digitalglobe.com), Navteq (www.navteq.com), Terrametrix3D (www.terrametrix3d.com), where geospatially accurate, texture-mapped 3D city maps are available for purchase off the shelf. LIDAR laser scanning technology is revolutionising surveying; city models are almost a commodity.”

Looking at London as an example, there are at least 12 3D city maps in development. One of the most impressive 3D plans comes from architectural modeller and illustrator, GMJ. Its laser-scanned GMJ ‘CityModel’ is highly accurate, down to the satellite dishes on houses.

As the images here testify, 3D maps on this scale really do capture the imagination. Many firms license areas of GMJ’s CityModel to use in development of new projects or to apply for planning.

GMJ has been using the model to examine and simulate the impact of global warming on the city, producing some startling images depicting the impact of a six metre water rise in the capital. The online exhibition was launched to coincide with the G8 Summit held in Japan last year, and aimed to increase public awareness of the predicted rise in sea levels.

Conclusion

We have the technology and information, so all that is now required is the buy-in of the right people. Digital cities are viable, easy to generate and offer huge benefits. They are slowly becoming a reality, though the majority of funding appears to be coming from institutions that are looking to drive economic development.

The problem appears to be the federated nature in which we break down and hand out infrastructure ‘fiefdoms’. Add to that the duplication of work done in the private sector with creation of the archipelago of ‘data’ islands.

We need a more co-ordinated approach to the use of all this data. If we are to get the benefits of sharing, we need buy-in at government or EU level for digital city projects to be mandated.

GMJ’s digital landscapes

The images shown here were created by London-based architectural imaging studio, GMJ. The company has pioneered the production of high-resolution photomontage imagery for verified planning visualisation, immersive virtual reality presentations and interactive real time 3D. Established in 1994, the company has an impressive client list that includes Foster and Partners, KPF, BDP, Make, and HOK Sport.

The GMJ CityModel of London is an impressive example of the studio’s work. The highly accurate model covers 40 square kilometres, including Southwark, the City and the West End. The sheer scale and accuracy of the GMJ CityModel would make an excellent ‘off the shelf’ starting point for a co-ordinated digital city of London, with all infrastructure and utilities information added – although no plans are yet underway. However, the GMJ CityModel has been used for many projects and can be licensed out for use by architects, local authorities or developers.

GMJ has also put the model to great use as part of its own online ‘London Futures’ exhibition, which offered visions of future city transport, clean energy generation and space saving solutions. Unfortunately, any future vision also needs to address the potential impact of global warming and the aerial view displayed here shows the effects on London of a six metre rise in sea level at spring high tide. The CityModel was used to predict the water levels across the capital for a number of alarming, yet thought provoking, images.

GMJ also plans to develop other 3D city models from around the world and offers a service to generate models to order at approximately 1.5 sq kms per week.