At London-based digital transformation and software development consultancy Remap, co-founders Jack Stewart and Ben Porter believe that the key to better buildings may lie in the ability of firms to create better tools for themselves

For those of us who operate in the built environment industry, our ability to catalyse change and to drive innovation is vital to our roles as future makers. As problem solvers, tool developers, technology wizards and tinkerers, it can feel natural to jump straight into solutions.

But what if we don’t quite know for what reason we should be developing a solution? It can be difficult to pluck from thin air innovations and new ways of doing things. Divine inspiration is often not the optimum route to a great idea or product. Instead, new ideas are often best identified through more general exploration of the broader domain that they occupy. At Remap, we’ve run numerous hackathons and foresight workshops with our clients, with the aim of teasing out such ideas. Understanding challenges in our industry, working through what might be creating them and then investigating emerging technologies for a response can result in great solutions

Critique culture

In early 2024, Ben Porter and I (Jack Stewart) co-founded Remap off the back of 10-plus years leading digital design at Hawkins\ Brown. As architects at Hawkins\Brown, we would design through a process of inquisition, participating in design charettes and the deeply ingrained critique culture of the profession.

Here, we tested techniques for rapid design exploration and evaluation. Collaborative design charettes are where a team of designers, community members and other stakeholders work together to develop a vision or design for a project. Critiques, meanwhile, provide feedback on how well design meets both user needs and client objectives. Generally, this approach focuses on the ‘why’ and the ‘what’ of design.

Find this article plus many more in the September / October 2025 Edition of AEC Magazine

👉 Subscribe FREE here 👈

But Ben and I were often curious about the processes that we undertake to design, as well as the technologies that we use to do it. Sometimes, it would feel as though there was a disconnect between designers and the tools that we use to do our work. In other words, it felt as if we, and our colleagues, were sometimes shackled by the design tools that we were using and at the mercy of those companies that build and sell them.

As we started to become more proficient in software development, we became aware of how good the tech industry is at testing, procuring and building new tools. At the most extreme end of the scale, open source culture in tech sees enthusiasts contributing to the improvement of software and platforms almost as a hobby. And for focused efforts, they typically run the equivalent of design charrettes and critiques, for ideas, process and functionality, in the form of hackathons.

As British architect Cedric Price said, ‘If technology is the answer, then what is the question?’ In a hackathon environment, we can discover what problems we need to solve and then rapidly prototype solutions.

Hackathons and heroes

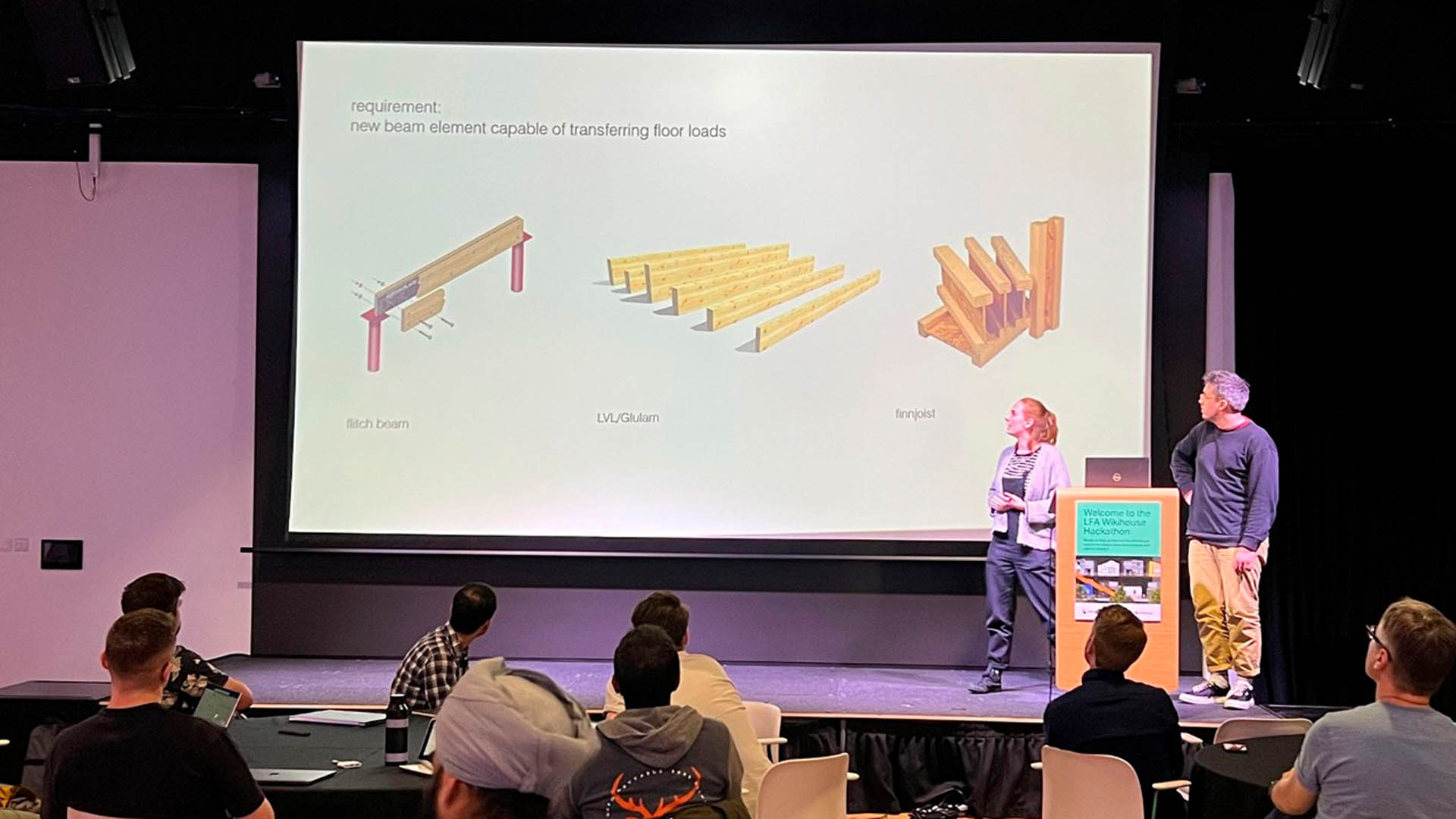

This piqued our interest and, during the 2022 London Festival of Architecture, we hosted a hackathon alongside Here East, Hawkins\Brown, and Wikihouse, bringing together a range of creative minds to explore new ideas for the Wikihouse system. The challenge was simple: ‘Build X, using Wikihouse, for the purpose of Y.’

In this scenario, X is the tool. It might be a digital tool, a physical tool, a building component, strategy or system. Wikihouse, meanwhile, is the framework – the modular system that this tool will work alongside and facilitate. And Y is the purpose or goal.

One team, with the purpose of ‘reducing waste’, developed a tool to turn plywood offcuts into furniture. Another, targeting ‘structural improvement’, proposed a new beam solution for spans wider than were previously possible. Finally, a team addressing ‘cost certainty’ built a handy API for instant costing of an itemised Wikihouse.

It was a super-successful event, with several ideas finding their way into the future Wikihouse development pipeline.

In 2023, while the seeds of Remap were being sown, we listened to a podcast by the Y Combinator, called ‘How to start a start-up’.

In the podcast, Wufoo founder Kevin Hale introduced his ‘King for a Day’ initiative, born out of frustration that so many great hackathon ideas never make it to production.

Often during hackathons, users are working hard on ideas about which, in reality, they are only semi-passionate. In King for a Day, one staff member is randomly chosen, and, for one day only, an idea about which they are truly enthusiastic takes centre stage.

We brought this to Hawkins\Brown in 2023, launching our first ‘Hero for a Day’. This was a callout for practice-wide suggestions to improve practice, design or delivery. Over 50 ideas poured in. From these ideas, ‘heroes’ were chosen and a practice-wide Digital Design Network was assembled to tackle the winning challenges.

In this process, we start by understanding the hero’s idea and then break the problem down into simple, testable steps using pseudocode. We focus on practical solutions, prioritising functionality over appearance, and on what we can realistically accomplish in a single, energised day.

Later in 2023, as part of an automation-focused callout, we requested pain points that could benefit from technology to either improve quality of output or make processes more efficient.

One hero suspected that modelling ceiling setting-out tiles could be automated.

During the session, the team developed a Grasshopper script to automatically generate layouts responding to the ceiling perimeter and structural penetrations. This could then be developed as a Revit add-in leveraged by Rhino.Inside.Revit.

The second hero, frustrated with the conversion of design documents from A3 to 16:9, led a team to develop an automated conversion process. During the session, the team documented how this process worked auto-manually, using InDesign buttons, then daisy-chained the functions together using Javascript.

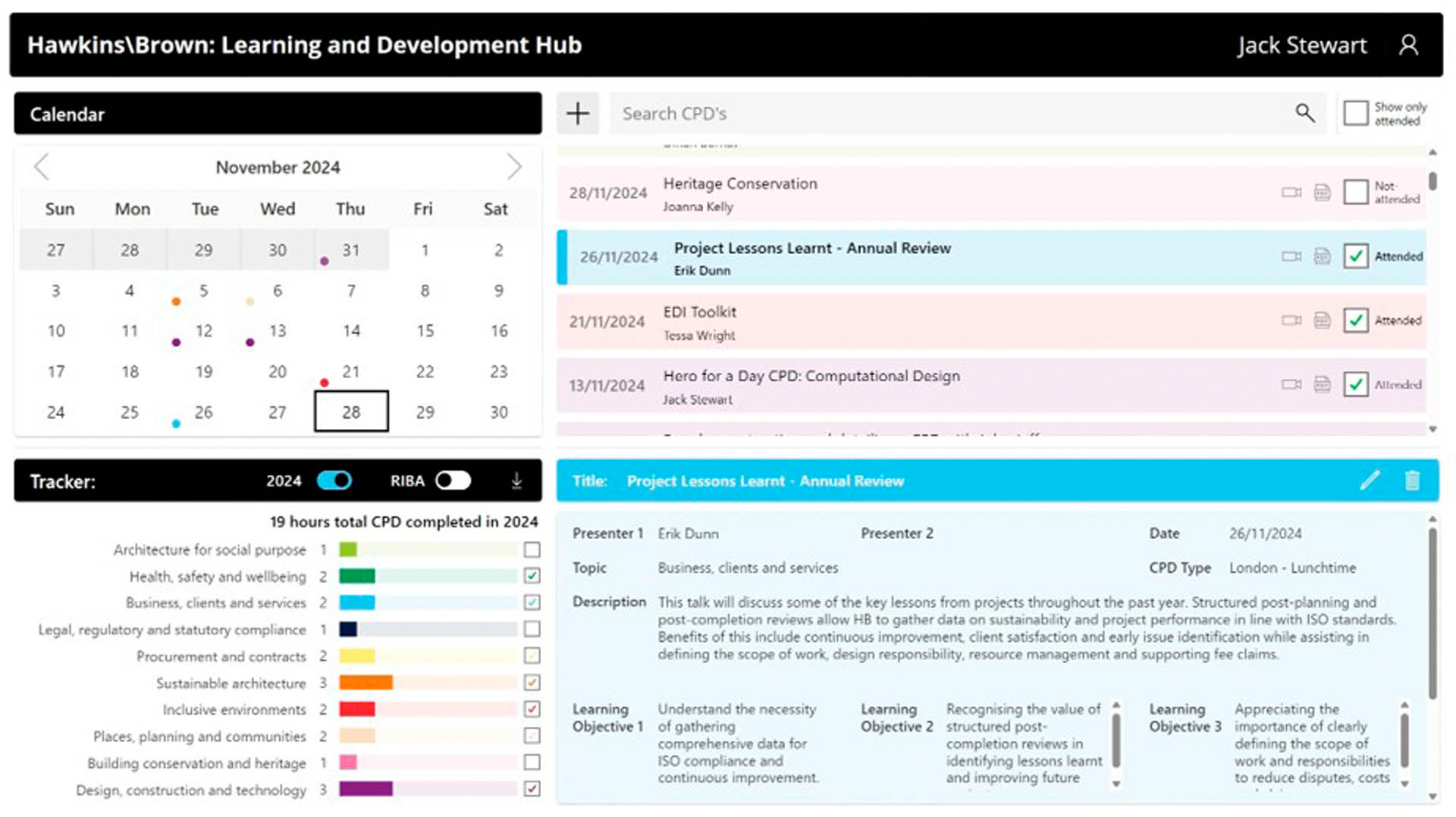

The third hero, in response to ARB and RIBA requirements to document CPD activities, developed an app to list, calendarise and track activities and attendance. This team’s app allowed users to easily download attendance records and access linked recordings and presentations.

We noticed that most pain points submitted were typically associated with automation, often broad in nature and had a practice-wide impact. To spark more project-specific innovation, we launched a design-focused Hero for a Day in 2024.

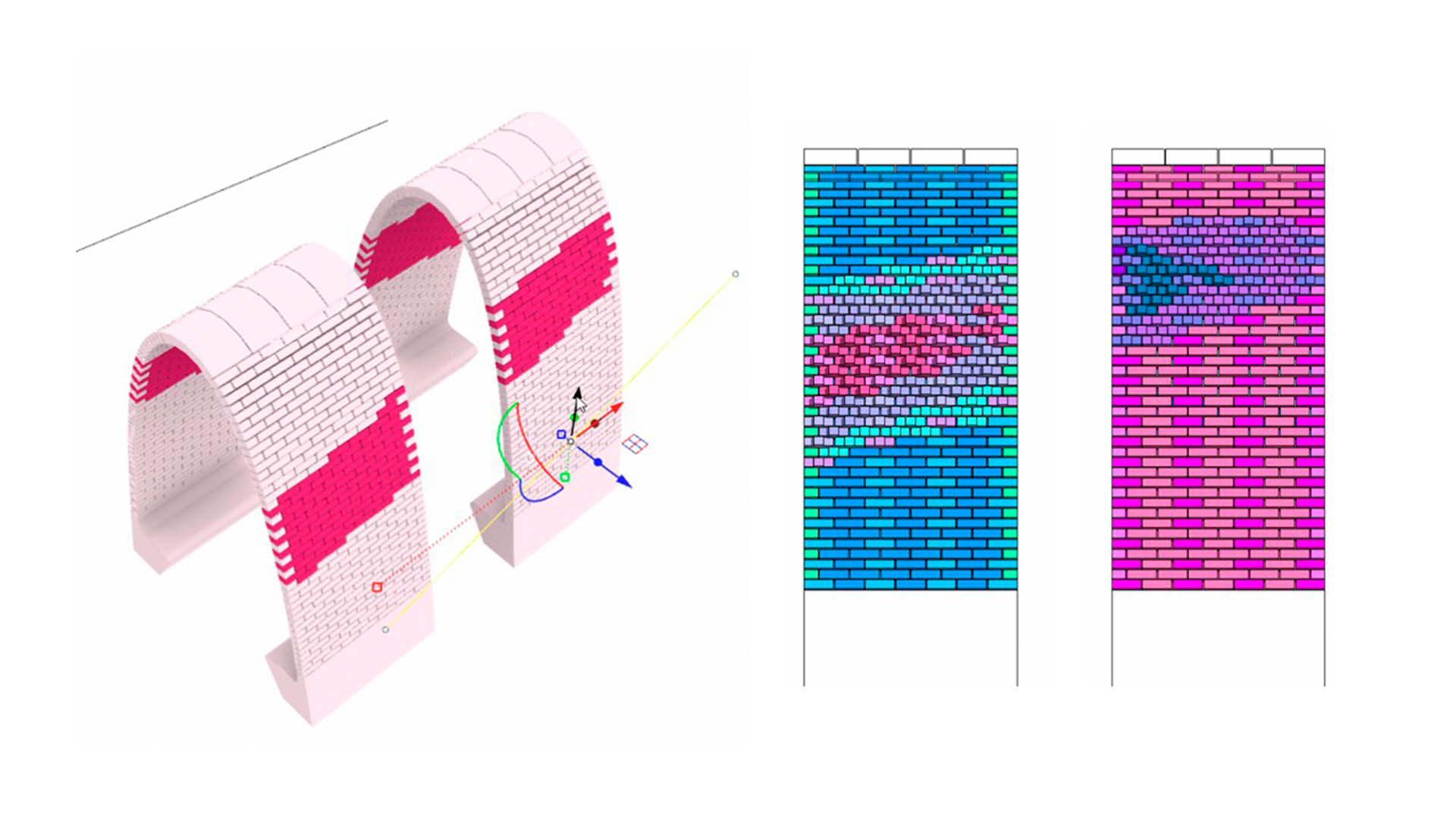

One highlight was the Arch-revival project, a computationally designed stone pavilion for Clerkenwell Design Week. Project leads teamed up with the Digital Design Network to create a design engine that automated brick arch layouts and enabled rapid exploration of variations in form and pattern.

Using Grasshopper, the team adjusted parameters such as brick size, mortar joints and arch shape, while attractor controls generated unique clustering effects. Integrating Rhino.Inside.Revit streamlined the workflow, enabling design changes to instantly update elevations and schedules, eliminating tedious redraws.

The result? A more complex, visually stunning pavilion that remained practical to build thanks to digital design tools. The final structure was a stand-out pavilion at CDW, and a testament to the power of computational design in real-world fabrication.

Hacking the future

These successes have given us great momentum. We have since run a forecasting workshop at BILT and hackathons at architecture firms Donald Insall Associates and Scott Brownrigg, with further events organised for later in 2025. These organisations are enthused about how techniques such as hackathons can help firms tap into the creativity and intelligence of their employees and use technology to build their own solutions to problems.

We are firm believers that to have ultimate design agency we need to be able to create & edit our own tools. That is really important to create great buildings.

Let’s embrace this challenge with the creativity, courage, and conviction it demands. After all, the future is not something that happens to us; it’s something we create. Let’s build it.