BIM has brought benefits, but it did not bring about the revival of the traditional ‘Master Architect‘ role for the profession. With attention to detail, understanding of fabrication and a high-power mechanical CAD (MCAD) system at his disposal, Kreod’s Chun Qing Li feels like he’s getting there

We are often told that history repeats itself. As a species, we seem doomed to keep reinventing thewheel. For the uninitiated, a recent discovery may look like the Next New Thing. For us older folks, those of us who have been around the sun a few too many times, the distinction between what’s ‘new’ and what’s ‘old’ tends to blur. And that, I guess, is why somebody invented marketing!

Architectural design was once a predominantly 2D exercise, accompanied by some physical models. When 2D CAD came along, we merely replicated the process on a personal computer. Then we had BIM, which puts 3D modelling first, to produce drawings and then PDFs. Ultimately, the deliverable has not changed — just our way of getting there.

But today’s BIM systems rarely collect enough detail to pass along to the next stage in the workflow: manufacturing and fabrication.

In other words, a chasm persists between BIM data and manufacturing data. In other forms of manufacturing — think of cars, aeroplanes, consumer goods and so on — a designer’s 3D model is accurate and modelled at 1:1 scale. And it is connected to a digital process, in which a number of other systems are involved, in order to generate assemblies (right down to the nuts and bolts, a bill of materials (BoM) and a wide variety of product manufacturing information. Business systems such as enterprise resource planning (ERP) software are integrated too, to produce costings and assess availability of parts.

There may still be 2D drawings on the factory floor, but the production of these is often wholly automated by core CAD systems. And these days, it’s not uncommon to see models get accessed at the point of manufacturing, too.

This begs the question: How might the AEC industry establish a ‘digital thread’ that extends further into the end-to-end process, delivers productivity benefits along the way, and helps firms manage the risks inherent to design and construction?

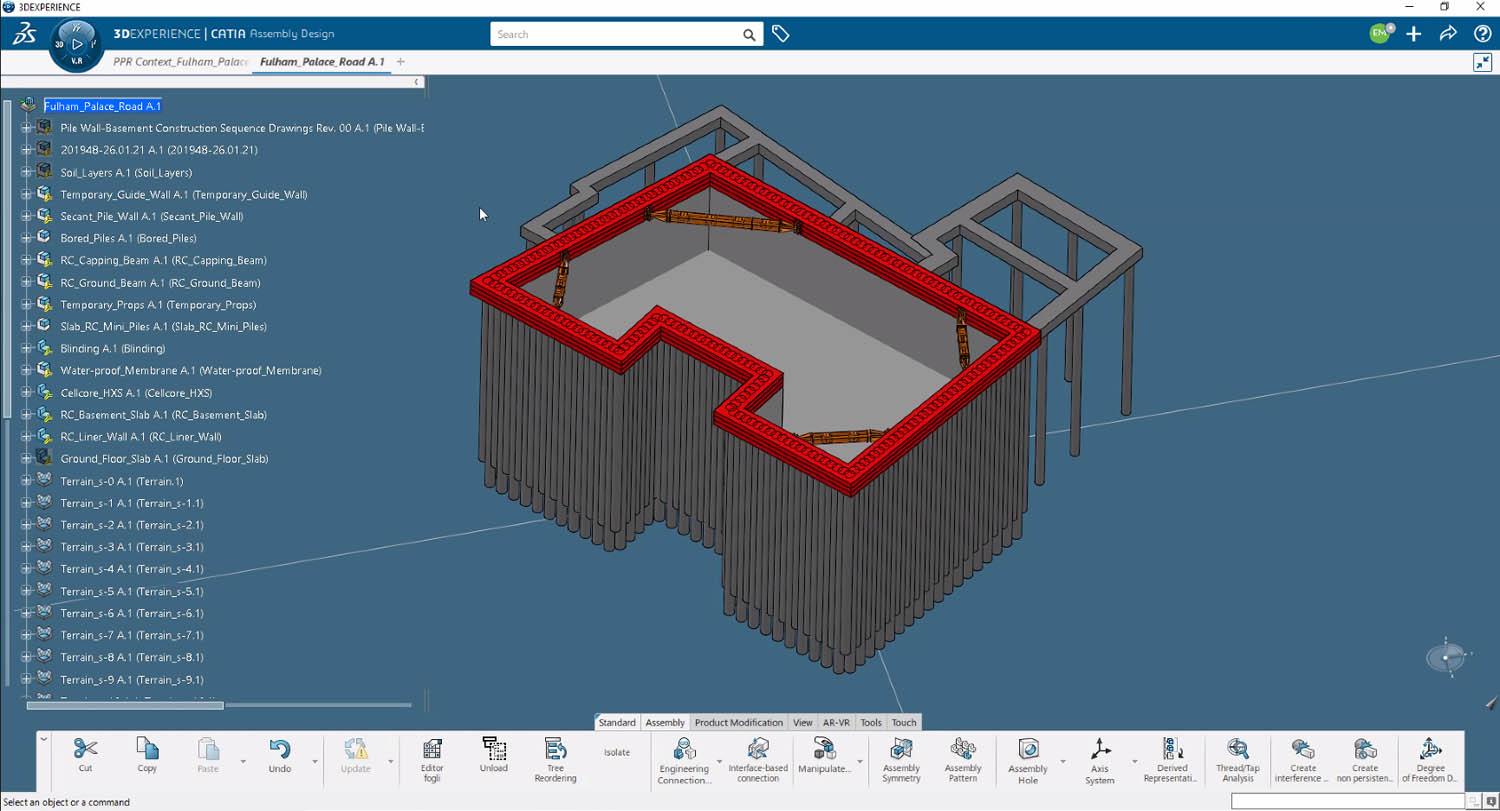

To date, a small number of architectural and construction firms have either augmented or ditched their BIM tools and adopted modelling software that is more commonly used in manufacturing in order to model at 1:1 scale, with high component detail. In this way, such firms are able to use design information beyond the design phase, to link it to fabrication, and to make it more accessible to downstream processes. In the process, they are in some ways becoming ‘master architects’.

Enabling design-to-construction

One such firm is Kreod, a London-based architectural and transdisciplinary practice, established 2012 by Chun Qing Li. The firm has built a reputation for the quality of its residential and commercial designs, and within the CAD community, it is particularly acknowledged for its approach to harnessing digital engineering and manufacturing.

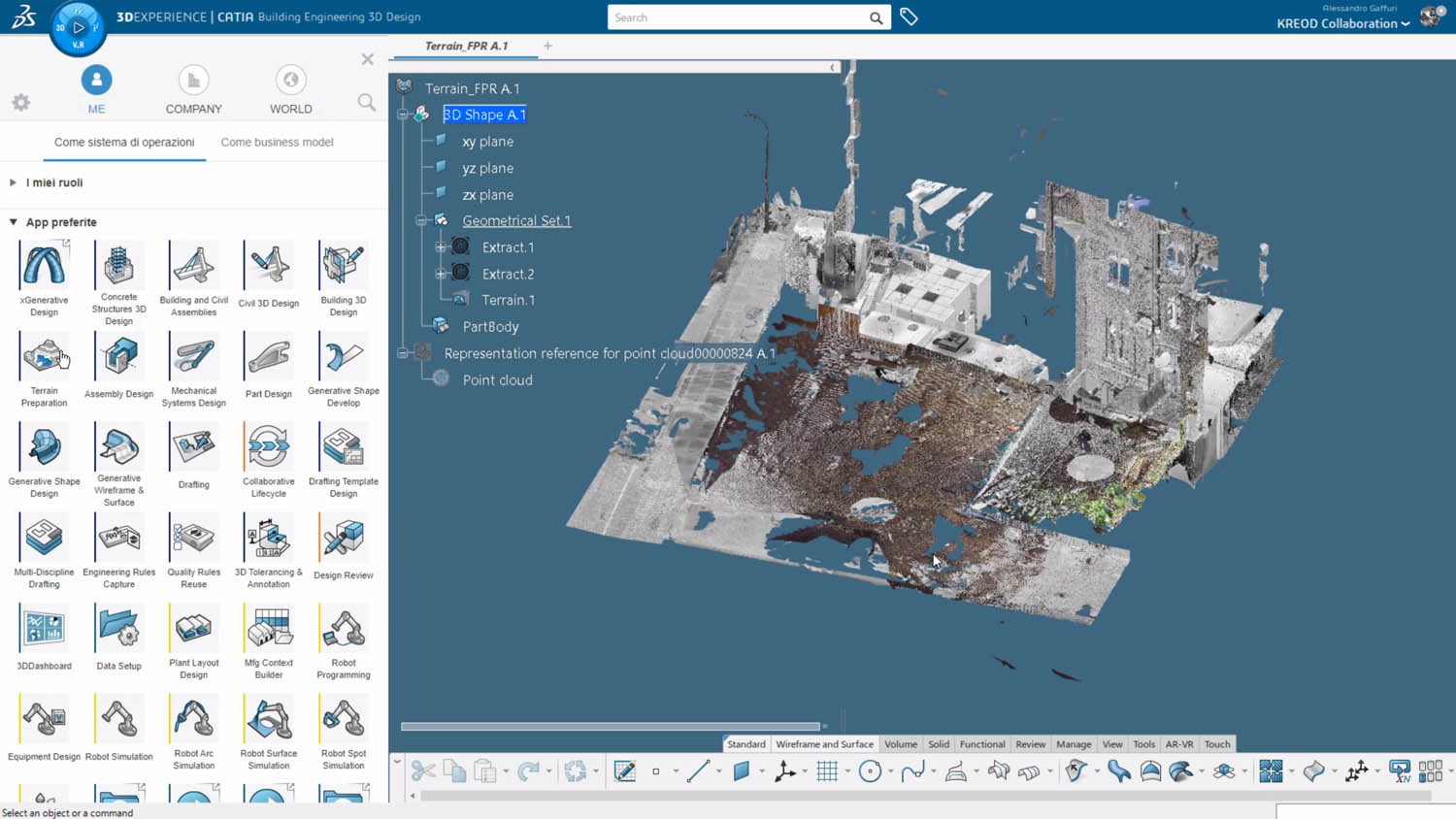

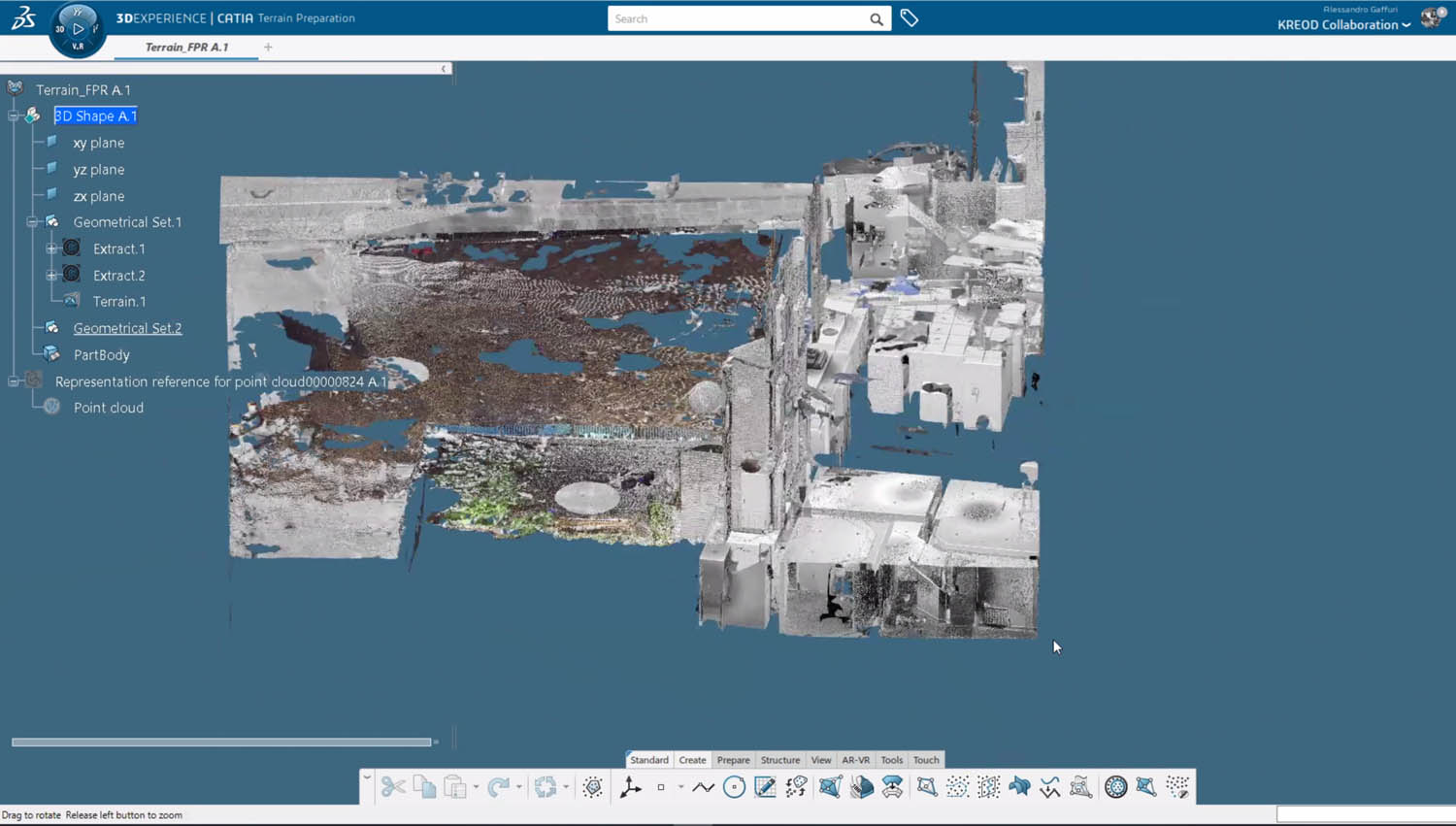

Li has, almost single-handedly, promoted the benefits of using high-end manufacturing software in AEC, replacing BIM with 3DExperience Catia from Dassault Systèmes (DS).

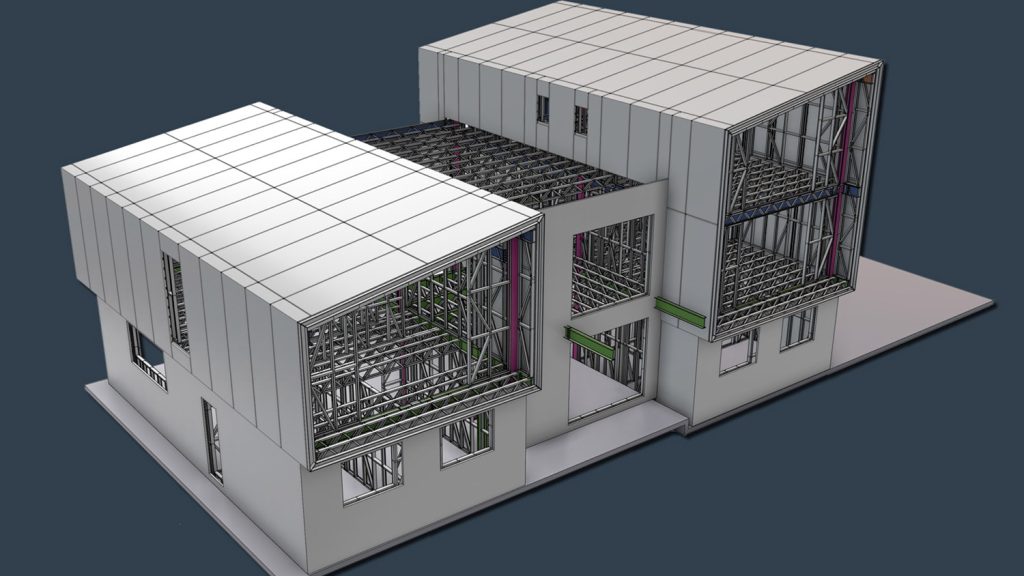

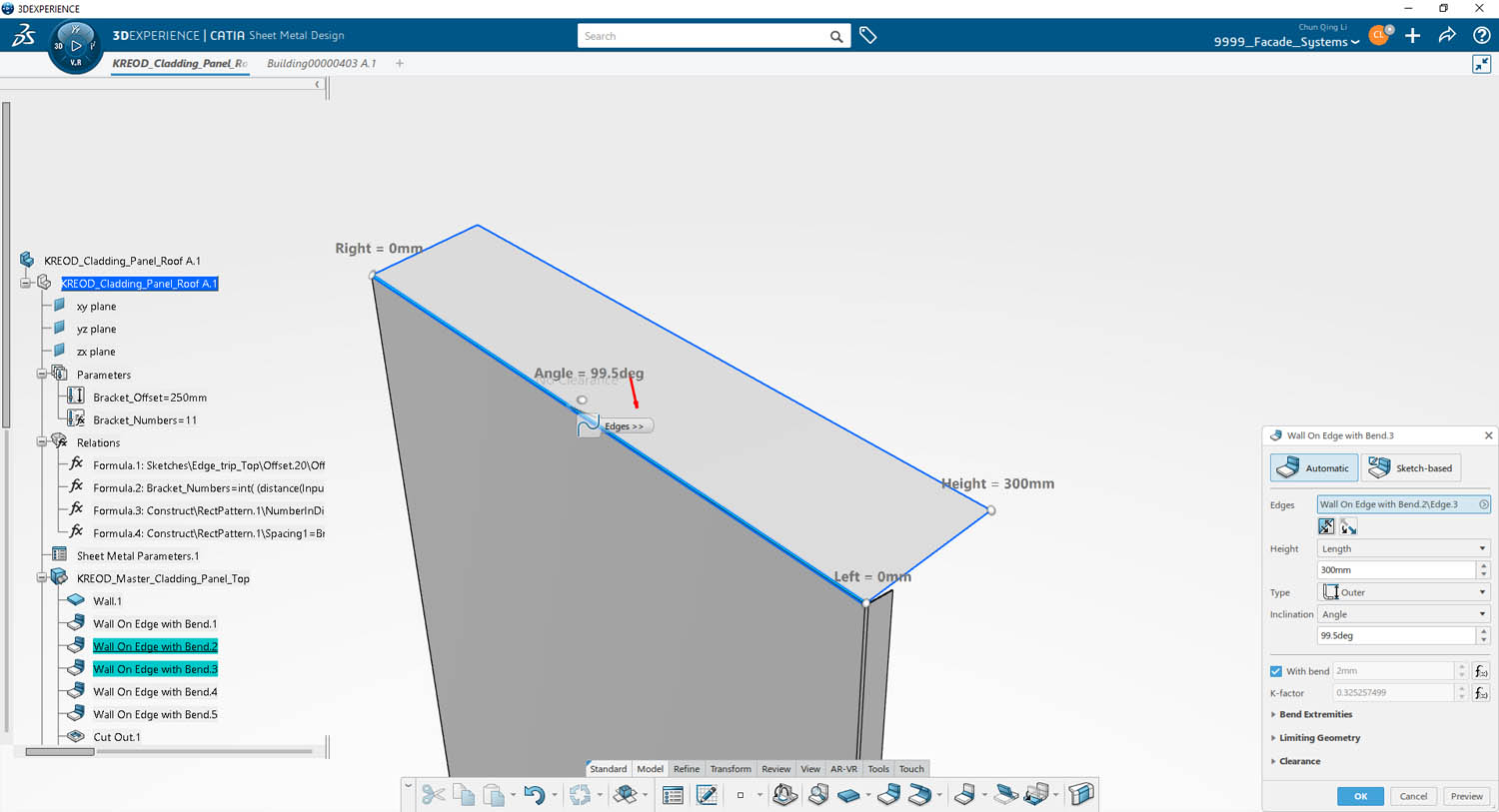

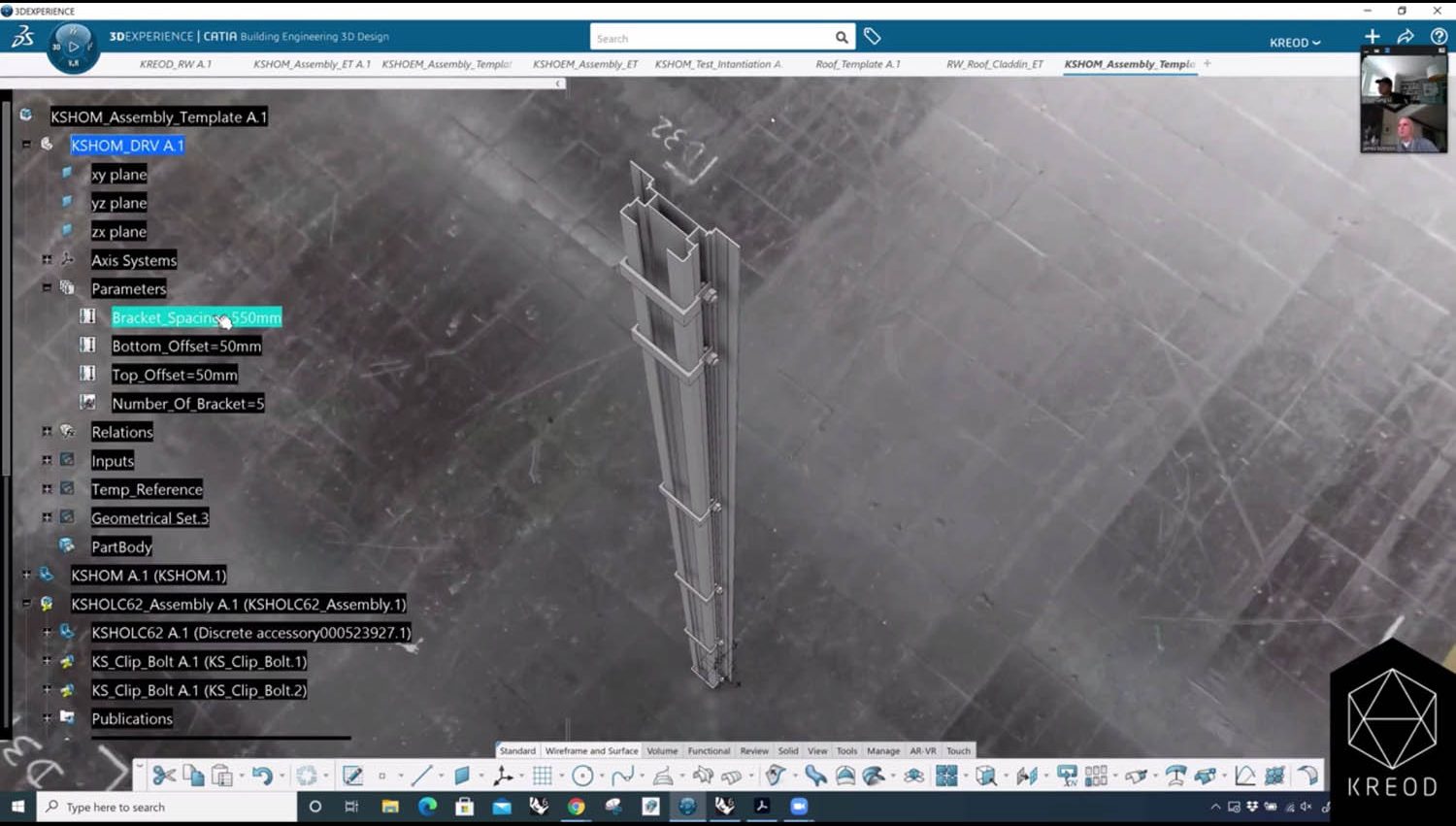

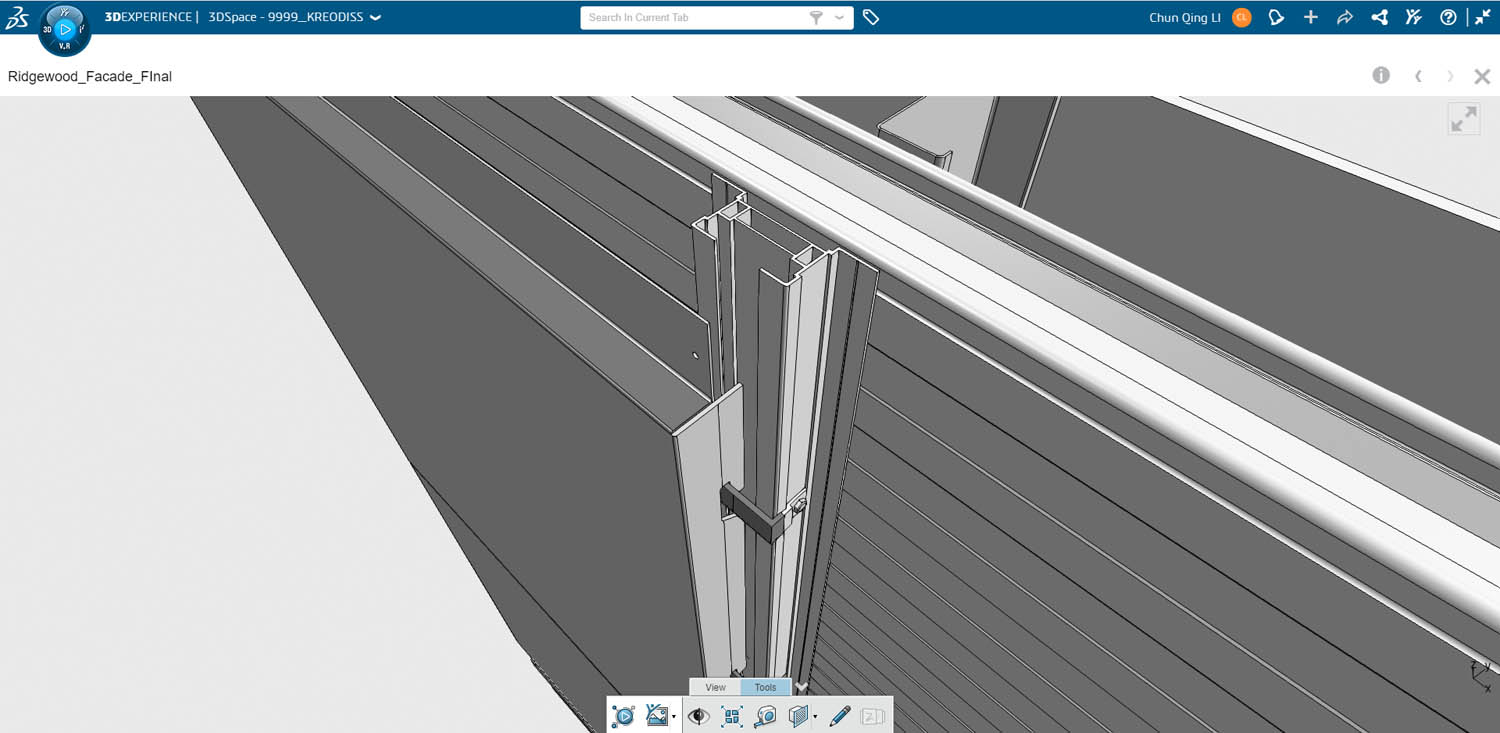

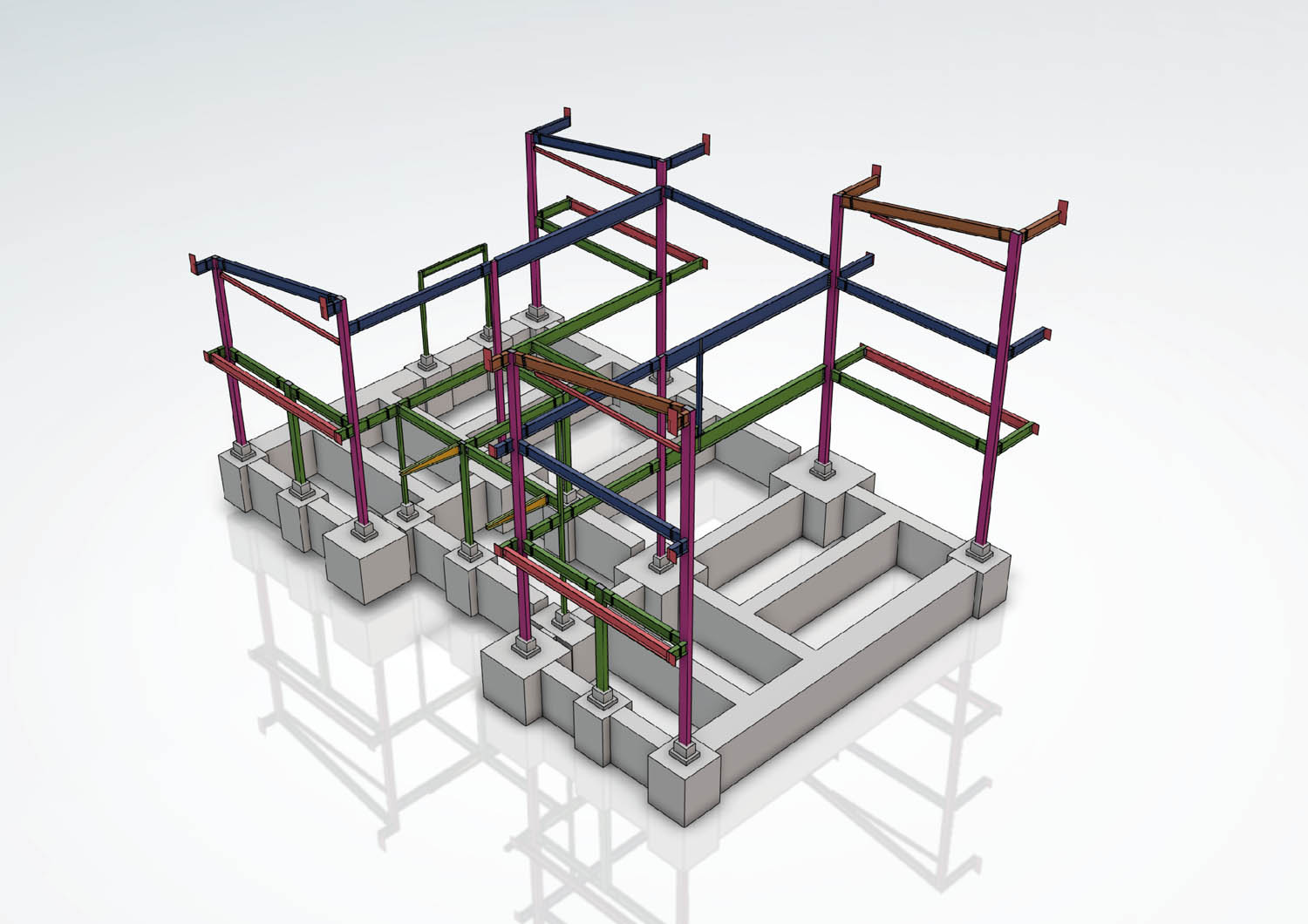

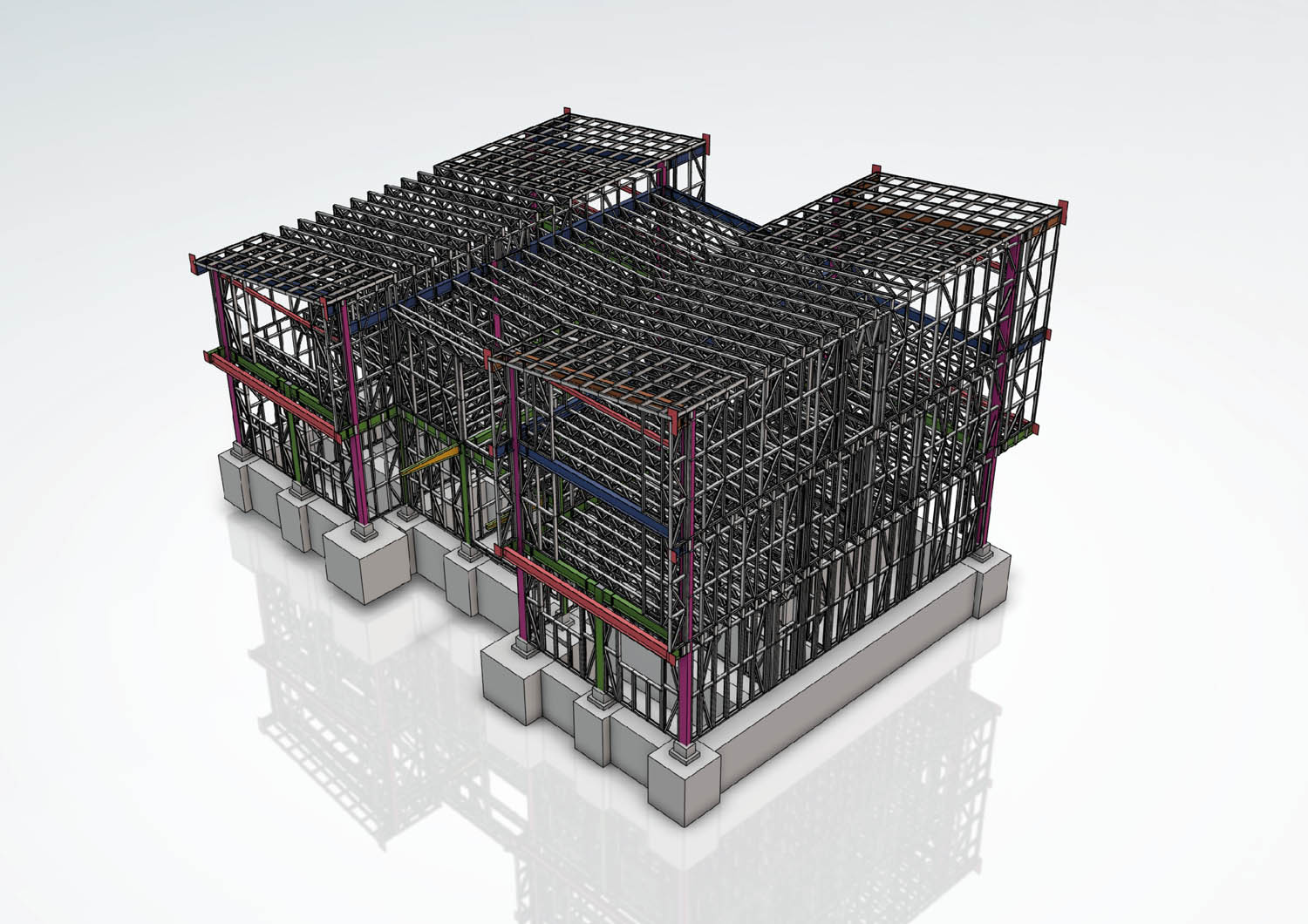

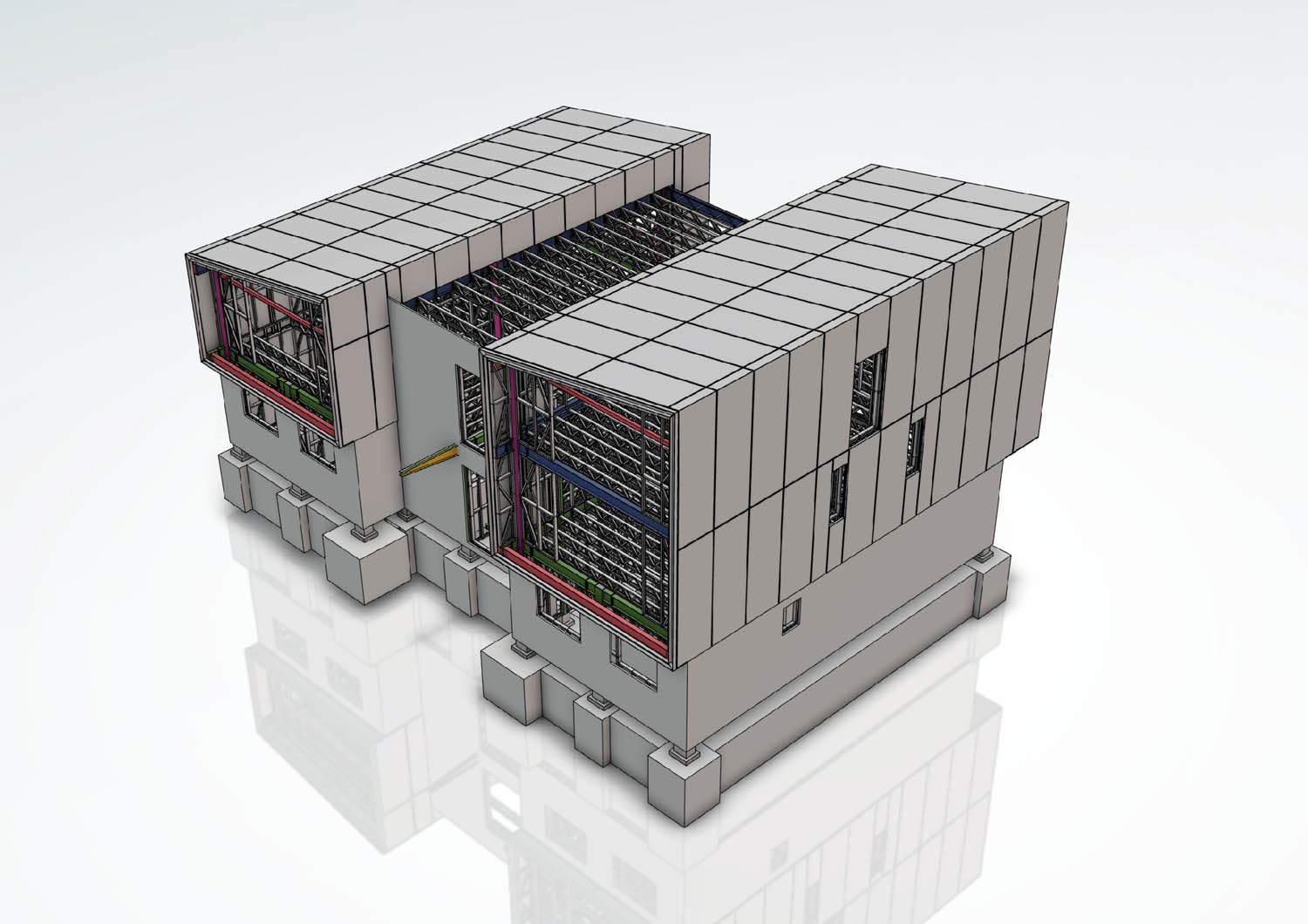

Through using the base software and developing in-house applications such as Kreod Integrated DfMA Intelligent Automation workflow (typically shortened to KIDIA), the company prides itself on the accuracy of its models, its bills of materials and, ultimately, the financial success of its sustainable projects. By modelling everything at a fabrication level of detail, Kreod has made great strides in minimising risk.

Kreod models every component in detail, right down to fabrication level, in order to truly understand not just design intent but also constructability, cost and all the connection details

It is also tackling the issue of procurement, at a time when rapid raw material price inflation is contributing to escalating build costs and, in some cases, forcing projects to be put on hold. One of the innovations that the Kreod team has developed is a web service for onboarding clients. This details the materials required for their project, along with live associated costs. In this way, clients stay informed about budget issues and can even make decisions around when to buy certain materials for a job. For the first time, clients can actually tap into the supply chain themselves, as opposed to having to rely on traditional contracts and hoping it all works out.

At the same time, by shunning established BIM tools, Li has seemingly opted to perform the equivalent of climbing the north face of the Eiger. It’s only after talking with him that you get a real sense of what has driven him to bypass the predefined walls, doors and windows of ‘Lego CAD’, and make geometry and manufacturing his key drivers in selecting a design system.

Kreod models every component in detail, right down to fabrication level, in order to truly understand not just design intent but also constructability, cost and all the connection details.

With each project, if the company is using a new supplier, or a new process, project leaders will visit the fabricator and invest time in understanding the fabrication process and limitations that they must consider during the design stages. The level of communication the firm builds up with its trusted suppliers means that design communication is dependable and can be model-based.

A fair amount of experimentation

On our visits to other leading architects, we certainly see a fair amount of experimentation with manufacturing CAD systems. While director of innovation at Aecom, Dale Sinclair was increasingly using MCAD tool Inventor over BIM tool Revit, to model modular projects destined to be manufactured off-site. Sinclair looks to have carried that vision with him to WSP, where he also heads up innovation. Revit was Aecom’s weapon of choice, but the level of detail at which the firm needed to model for fabrication would have led to huge models, impacting Revit performance and potentially making the system unusable for this purpose. By contrast, MCAD tools are optimised to run with models comprising tens of thousands of parts. Very high-end systems can handle even more.

Kreod may have eschewed the comforts of ‘Lego BIM’, opting instead for the certainty of extreme detail – but in the process, it has brought upon itself a great deal of additional modelling work

This approach may not be for the faint hearted — but it is for the engineering-minded. It also suits those AEC professionals who want to use digital tools to be involved in the whole end-to-end, design-to-build process. The upside for clients, meanwhile, is that firms that model in detail and know a great deal about fabrication costs upfront are better placed to offer a full-service, singlepoint-of-contact approach, managing everything from design to delivery.

The industry is very slowly waking up to the connection between choice of design tool and project outcomes. At present, that awareness tends to be limited as being where the industry needs to focus. And, as discussed, fabrication considerations need to take place early in design processes.

This forward-thinking mindset is not dependent on the size of a firm. It can be seen both at Aecom (50,000 employees) and Kreod (fewer than 10 employees). AEC Magazine contributor and Foldstruct CEO Tal Friedman refers to it as ‘Fabrication Information Modelling’ or ‘FIM’, where designs are created with built-in knowledge of eventual production methodology. Li prefers the tried-andtested DfMA (design for manufacturing) label, but ultimately, we are talking about the same thing.

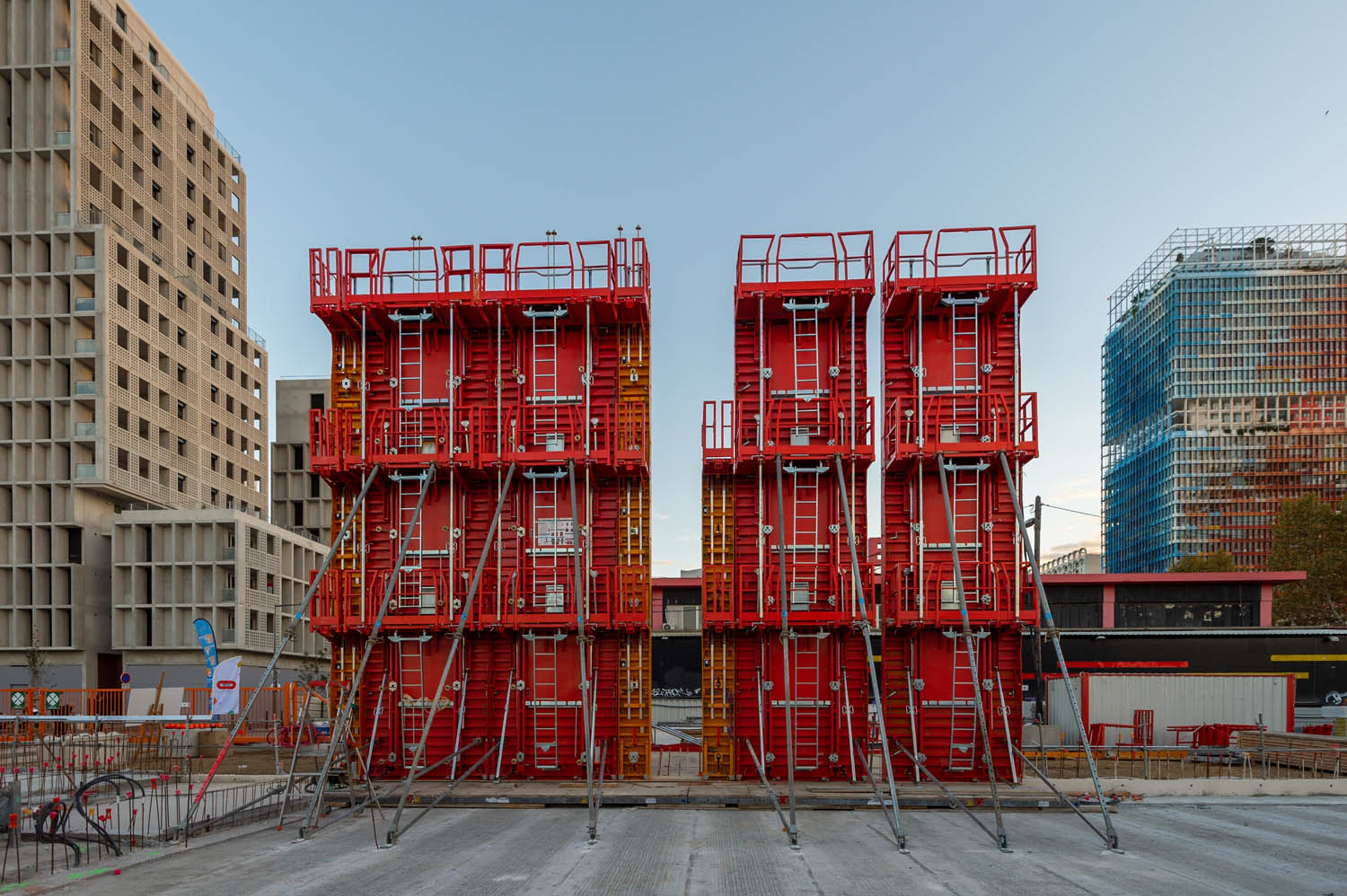

The big problem is that there is no commercial turnkey system to provide this. Every manufacturer has varying capabilities. In 2017, Bouygues paid Dassault Systèmes to custom-build a system to automate the stripping of models from Revit into their component parts in order to build an optimised, manufacturable model, with drawings, full costings and lean project management using Dassault Systèmes’ 3DExperience environment. Bouygues is looking to expand this system to include sustainability analysis and optimisations, too.

Maybe this is the way the industry will go, with traditional, federated workflows for some sectors, using off-the-shelf BIM tools, while others adopt bespoke systems to fully automate assembly models and drive fabrication.

Looking at what we have today, along with where we need to go tomorrow, if AEC is to embrace a completely digital end-to-end process, it seems unlikely that today’s 2D-focused BIM tools can evolve to keep pace.

Kreod may have eschewed the comforts of ‘Lego BIM’, opting instead for the certainty of extreme detail – but in the process, it has brought upon itself a great deal of additional modelling work. That said, the more work Kreod does here, the bigger its own library of parts, so there will be payoffs.

It will be fascinating to see what software and services Kreod decides to bring to market in order to assist the industry. From our conversation with Li (see boxout below), it’s clear he likes to have a lot on his plate. In return, he’s giving the industry plenty of food for thought.

What is 3DExperience Catia?

3DExperience Catia is a long name for a big CAD system. Catia is the flagship modelling ecosystem from French developer, Dassault Systèmes. As CAD systems go, the current version, V6, is the Ferrari of the manufacturing CAD world. Indeed, it’s used by Ferrari and its F1 team, as well as Porsche, BMW, and Toyota. In aerospace, both Boeing and Airbus are customers. Catia covers individual part models, assemblies (of parts), very high-end surface modelling, Finite Element Analysis, Structural Analysis, generative design, sheet metal folding, rendering and so on. The design tool is connected to other DS brands, Enovia (collaboration), Delmia (supply chain planning) and Simulia (simulation), amongst others.

The 3DExperience part of the name relates specifically to its ability to operate beyond the desktop and to work in the cloud, connecting to other parts of organisations with web-based model and business process management tools. This is commonly known as PLM (Product Lifecycle Management) in manufacturing circles.

Catia is not commonly seen in AEC firms. It’s viewed as an exotic choice. However, some exceptional practices are famously associated with its use. These include Frank Gehry, ZHA (Zaha Hadid Architecture) and more recently, Lendlease. We’ve also heard rumours that Laing O’Rourke might be experimenting with it as part of the company’s ongoing research into modern methods of construction.

Before Catia, Gehry had trouble getting his buildings built, because contractors would add a big percentage to the estimates, arguing that 2D drawings left too much to the imagination. When he switched to sending Catia models, all bids came in within 1% of each other.

Kreod is thus following in famous footsteps. In doing so, it has opted to build its own layers of functionality to enable the rapid detailed modelling of architectural and construction elements, down to every nut and bolt.

Chun Qing Li is looking to bring all the knowledge his team has amassed in design to fabrication modelling to offer on demand, online service to the market. Watch this space.

Kreod Olympic pavilion

The Kreod Olympic pavilion (London 2012) was designed to showcase modern design and innovative construction techniques. The unique form of the structure was made possible through the use of cuttingedge CAD technology, enabling it to be manufactured in modular form with minimal waste material. Prefabricated sections were quickly and accurately assembled, ensuring that construction could be completed within a tight timescale before the games began.

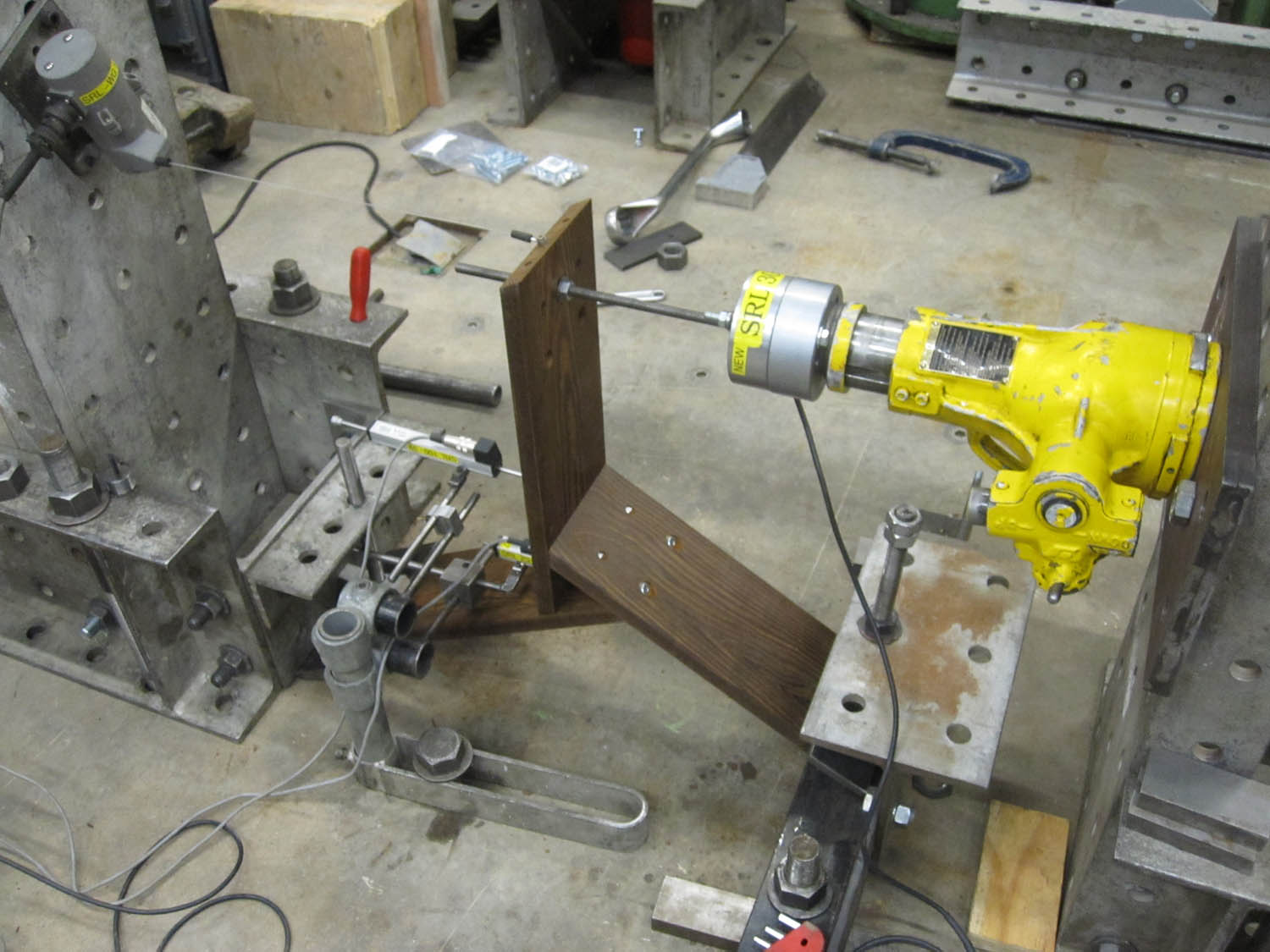

Innovative manufacturing processes such as laser cutting, vacuum casting and CNC machining enabled the creation of the intricate details that are a feature of the finished structure. During the build process, precision CNC tools cut individual components from a range of materials, including aluminium, stainless steel and composites. These were then hand welded together to create frames for a lightweight shell covered with wood panelling. The high accuracy of modelling and CNC-cut parts meant that each part fits perfectly, despite a wide range in variances.

Chun Qing Li describes his approach to creating the Kreod Pavilion as follows: “Our vision was to provide an exciting showcase for some of London’s most dynamic designers working in 3D-printed structures; making full use of contemporary technologies, while still meeting all relevant safety regulations.”

Kreod’s Olympic Pavilion demonstrates the potential of combining modern design and manufacturing technologies with digital building processes, offering a practical example of how custom structures can be created faster.

Q&A with Chun Qing Li of Kreod

AEC Magazine sat down with Chun Qing Li, founder & CVO of Kreod, to learn more about his non-conformist approach to BIM workflows and discuss his views on how and why the industry needs to change.

AEC Magazine: While there are a number of mature BIM applications out there, you have chosen to go with a CAD system more popular in high-end manufacturing. That’s meant developing your own layers of functionality — so what on earth made you do that?

Chun Qing Li (CQL): I feel that, as architects and designers, we have been kind of hijacked by the software companies. Because we are creative people, we have different mindsets to engineers, and the software companies develop tools created by software engineers who don’t necessarily understand how we work. We always have to bend ourselves and learn their logic. In my experience, it’s counterproductive. The tools we have as off-the-shelf solutions for AEC just don’t make any sense to me. For example, with BIM, we spend a whole load of time modelling a beautiful, 3D datadriven design, but ultimately end up delivering 2D PDFs. It just defeats the whole purpose.

AEC Magazine: But how much of that is down to the technology failing to map to dumb contractual constraints and deliverables?

CQL: Everything’s driven by the principal contractors. While architects may be using Graphisoft [Archicad], Revit and other interesting packages, in construction, they are still beholden to 2D drawings. That’s the thing, and the contractors mainly use 2D packages and specifications. I feel a sense of urgency that we need to change this, but obviously my company is very small, and I don’t have a marketing budget to educate the industry! When I started developing the software, I tried to convince developers and contractors that there was a better way of doing things, but they said that they didn’t want to be guinea pigs. So, I started my own construction company. Now, we are building things and we are our own guinea pigs!

We started with our own architecture firm, and from our in-house development work, we launched a multi-tech start-up to share our solutions, the first of which was an intelligent automation tool. This will eventually enable us to bring to market a complete platform that will integrate design with procurement and supply chains. This system will be able to get prices immediately, instead of relying on a QS (Quantity Surveyor) benchmark estimate. When we launch our platform, clients will be able to access our system and pick, choose and buy products from the catalogue.

As to contracts, based on all our in-house process development, we have introduced what we call ‘open book contracts’, so that when we talk to a client, we are incredibly open with materials costs, down to the brick, as well as all the preliminary costs and even our profit margin.

AEC Magazine: You sound very frustrated looking at the AEC workflows that have been adopted and codified?

CQL: The RIBA Sequential Work Methods have a linear format which necessitates sequential focus on phases, one at a time. Each stage must be completed before the next is initiated, leading to a drawn-out development process with intensive design alterations, delaying projects and having financial implications for all involved. Linear workflows, by their very nature, build in risk, not eliminate it. From a commercial perspective, I understand that the method makes it easier to break down payment phases, but I think you can simplify the whole workflow.

In manufacturing, they have refined the process. They produce 3D models that are manufacturing-ready. They do assembly sequencing, as in how you put things together, while we as an industry, we produce hundreds or thousands of drawings, bundle them up and throw them over the fence!

Our specific workflow, which we call KIDIA (Kreod Integrated DfMA Intelligent Automation) is specifically designed to eliminate the need for repetitive work. It enables an early and accurate calculation of cost by automatically creating the necessary manufacturing/fabrication code and bill of materials (BOM). KIDIA not only expedites RIBA Stages 2, 3 and 4, but can also potentially save up to 90% of the time spent doing it, all while eliminating or reducing risk, which can be seen in our contractor quotes.

AEC Magazine: Some may say that it’s extreme, opting for an MCAD system versus a BIM platform that was custom made for architects?

CQL: I think that the whole process has to be integrated on a single platform. Otherwise, you end up using all sorts of applications: Rhino, Grasshopper, SketchUp, AutoCAD, Excel spreadsheets and Revit. And the best the industry could do to join them up was IFC, which is a lowest common denominator format.

I guess like most of us, toolswise, I have been on a journey. I started off using MicroStation and Generative Components (GC), then moved on to Rhino and Grasshopper. Then I started to get into geometry rationalisation and teamed up with a professor of mathematics from ETH Zurich who did it all in C++, no CAD system required!

Experience is essential. On the Olympic Pavilion project, I was the lead designer, the client, the contractor and the project manager! I had to do everything, apart from structural engineering. After rationalising the geometry, I built what I called at the time a ‘building manufacturing model’, though I found out later it’s called DfMA. I found a second-hand robotic arm and started experimenting with cutting and assembling wooden frames for the pavilion. For the metal frame, I collaborated with a steel fabricator and took a highly collaborative approach, which was great. I learned so much.

AEC Magazine: How on earth did you fund the Pavilion as a personal project?

CQL: I pitched everyone! I had a fulltime job. I think I spent £2,000 on stamps, writing to a lot of people and companies. I just sold the idea and made it possible!

AEC Magazine: How did you get involved with Dassault Systèmes and the 3DExperience Catia platform?

CQL: Frank Gehry was the pioneer. He developed Gehry Technologies, with his own Catia tools for architectural designs. For us, this is a financial decision, a commercial decision, to go and find the best platform which can go all the way to fabrication and then develop on top of it. The 3DExperience platform is very powerful and can handle lots of complex information. It’s why it’s so popular in aerospace and automotive.

Initially, when I first contacted DS around 2010, they said they didn’t really work with one-man bands or students. They worked with multi-billion dollar engineering and aerospace firms and that was the end of the conversation! Later, things bounced back, especially as they created an on-boarding programme for start-ups and started to see potential for their applications in AEC.

AEC Magazine: So how do you think this is going to play out? AI is starting to appear at the edges and some systems will take polylines and deliver fully detailed 3D models, with drawings for fabrication. Are we going to see more design/ build firms? Will we need fewer architects?

CQL: I use the term ‘Digital Master Builder’ from the traditional meaning, dating back to the mid-sixteenth century, where architectural designers were closely involved in the whole construction process.

We have self-restricted the role of architects to just delivering design intent. Back in the day, architects used to lead the process, but now we lack broad industry competence and there is a general lack of interest in understanding the construction side of the business. There’s a shift in the way we work, where the principal contractor is now playing a major role in the entire process.

Through our plans for development, I want to give more power to the architects. They will be the designers that will understand the costs. That’s how we sell our schemes. We need to widen our spectrum, not just be the producers of couture drawings with beautiful line weights. Buckminster-Fuller asked Sir Norman Foster how much his building weighed? We need to be more like BuckminsterFuller, who was obsessed with the relationship between weight, energy and performance — of “doing the most with the least”. And, of course, customers want to know the cost. We need better tools to do this.

AEC Magazine: You have started a lot of different firms with different aims. What can you tell us about them?

CQL: There’s a reason we started these companies, for architecture, software development, and especially construction, because in each, I need to build, to demonstrate and deliver. From our experience, we can convince more customers to use our technology or consultancy. That’s the notion. Ultimately, we have to do something to better serve architects and developers and the key is to integrate the whole process. To provide more transparency, with design costs understood, which means there will be less need for damage control at critical points in any build.