The discipline of mainstream architecture is at an all-time low. Generic repetitive design, low sustainability and low cost / time efficiency have become the new norm. Despite the digital transformation in the field, we have failed to leverage BIM tools for creating a better built environment. But not all is lost!

Advanced AI modelling techniques, together with robotic fabrication, promise to create the much-needed revolution in what we design and build. But these steps require us to disrupt the nature of architectural practice. So, what really needs to happen for the industry to succeed and are we really ready for such a change?

Einstein once said the definition of insanity is to do thre same thing over and over again and expect different results. Yet here we are, designing the same buildings, over and over again and expecting to decarbonise, save cost/time and improve architectural design — surprisingly, to no avail.

Responsible for 40% of CO2 emissions and growing socio demographic problems as results of living standard gaps, it is time to admit modern architecture has failed us.

It has failed to use technology to guide it to its goals due to fear of disrupting its own centralised power structure. In fact, the most common question raised when speaking about design automation is the concern for the well being of the architect rather than the well being of society and the built world.

However, new AI technologies at hand can empower architecture to get back on track and democratise construction. It’s time to go back to the drawing board and replan planning as we know it.

The rise and fall of the architect

The architect, who has taken the historic role as guardian of architecture, has let its guard down and allowed a new player to dominate the realm, replacing the soft and often vague term of “architecture” with the hard and empiric term of the “construction industry.’

This is not new, of course. The architect has changed its role many times throughout history: from an on site omni present design-builder, to a “behind the desk” paper draftsperson and all the way to a computational specialist living in a virtual universe. What has always remained at the heart of the discipline is the desire to create a worthy living environment.

However, the shift from a physical on-site methodology to a world of data and theoretical geometry has disconnected the discipline from the ground to the point where the modern architect is merely a nester/drafter of repetitive shelf products that compose buildings.

As a matter of fact, it is fabrication restraints dictated by producers and contractors that limit 99% of the buildings to repetitive boxes from early design stages. For the average architect, it is a given that any deviation from the norm will create an exponential price increase due to the added engineering and customised production. ‘Starchitecture’, on the other hand, is a game reserved only for those privileged enough to have unlimited budgets.

In short, we have become strong on data, clouds and documentation, but weak on design flexibility and well being — aka architecture.

So yes, we have managed to build mega cities higher, quicker, and more industrialised. Yet, the industry fails to meet its own success criteria, deepening the problem year after year. Just like in the story of the tower of Babylon, our success is exactly what is leading us to our failure. So why should we be optimistic?

Build like a robot, sing like a human

Automation tools and robots have created the fourth industrial revolution in fields like automotive and aerospace and are now more feasible than ever before for mainstream construction. It is estimated that since moving to the age of advanced automation, the price of a car has relatively dropped by about x3, yet construction is getting more and more expensive due to growing labour costs. Robotic tools like 6-axis robotic arms from KUKA or life-like robots from companies like Boston Dynamics and Festo have led to a new age of mass-customisation.

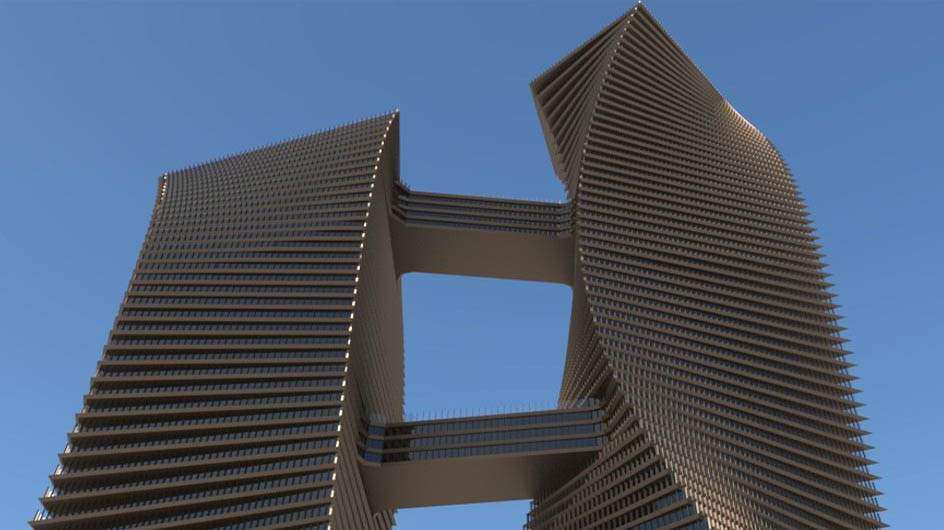

But it wasn’t just the robots themselves that changed the game. More importantly, it was the ability to control them using digital DfMA (Design for Manufacturing and Assembly) methodologies. Now, these powerful tools are at the fingertips of the construction sector, we no longer have to think in terms of moulds and stamps. Instead, we can begin to design in free forms and new morphologies.

So how do you teach your architect or engineer next door to design for a machine, let alone a fabricator who is using traditional tools? After all, it took us thousands of years to come up with methods that match the human labour restraints. The answer: a singularity in the design process that connects all stakeholders to the same model, from initial design, all the way to fabrication and takes into account time and cost of building from preliminary stages. We now have the means to do so, if we only dare to step outside the box.

Make architecture great again

The magic moment in architecture is the awe of seeing a design come to life and being surprised by the outcome you designed yourself. Undiscovered spaces form hidden gems. Reflections and lights tell more than meets the eye.

With AI, we can achieve new levels of self-forming designs that will have to match our design goals as a principle, but have a free hand on how to get there. Technologies like GAN (generative adversarial network) and ML (machine learning) have the power to create unimaginable forms and functions if we only dare to open that door.

The building of tomorrow will have a life of its own and be based on an adaptable DNA, varying on needs and project goals, rather than design ownership of a single entity. The architect in that sense will have to give up a lot of the authorities it had as an individual designer, but in return gain access to a new world of opportunities. The boundaries must blur between an architect, engineer and manufacturer, and turn the building into a living product. We must guide, select and choose, rather than dictate. In the work of Foldstruct, the aim is to democratise the planning process and mix between endless data combinations in a platform where architecture is a metric and not a title.

So what will the future of architecture hold in an age of automation? Will it kill architecture as we know it, or return it to its old glory with a new twist?