Nobody ever thinks their workstation is too fast – it can always go quicker. Speed is usually addressed with bigger processors, but developers are now looking at smarter ways to harness the power inside, writes Greg Corke

For years, BIM and design visualisation software has relied on a brute force approach to boosting performance. If you want renders back quicker or models to move more smoothly in the viewport, simply throw more processing power at the problem.

And why not? In many cases it works extremely well. You only have to see what AMD’s 32-core Threadripper CPU can do for render times to know there’s plenty of mileage in this ‘bigger equals better’ approach.

But it doesn’t always work. Take, for example, the long-standing issue of poor 3D performance when working with large models in mature CAD and BIM software: no matter how powerful your workstation’s GPU is, frame rates will simply not go up. Much of this is down to the fact that the code is old and simply not designed to take advantage of modern GPU hardware.

Rather than tackle the issue head on, many CAD software developers have chosen to simplify the way models are represented in the viewport. But things are now changing. The new beta graphics engine in SolidWorks 2019 allows users to move huge 3D models smoothly without compromising visual quality. It works by putting the GPU centre stage.

For years, the GPU took a supporting role when it came to 3D graphics. When modern CAD software was first developed, the GPU didn’t have the power to take on so much responsibility, nor did the graphics APIs exist to allow it to do so.

With the new OpenGL 4.5 graphics engine in SolidWorks 2019, assemblies that previously only used 5% to 10% of the GPU’s processing resources are now maxing out high-end graphics cards. The performance increase is quite phenomenal, breathing new life into old hardware. We hope to see BIM software developers follow suit.

While this is a case of taking good advantage of modern APIs, other software developers are exploring new ways to get more out of a workstation’s GPU. In 2017, Ansys shook up the world of simulation software with Ansys Discovery Live, a new tool that promised ‘instantaneous simulation results’ by accepting a small but manageable trade-off in accuracy. Importantly, it used the GPU in a different way to other simulation tools. Instead of focusing on absolute precision, the development team asked the question ‘what would be good enough for design exploration?’, and harnessed the power of the GPU accordingly.

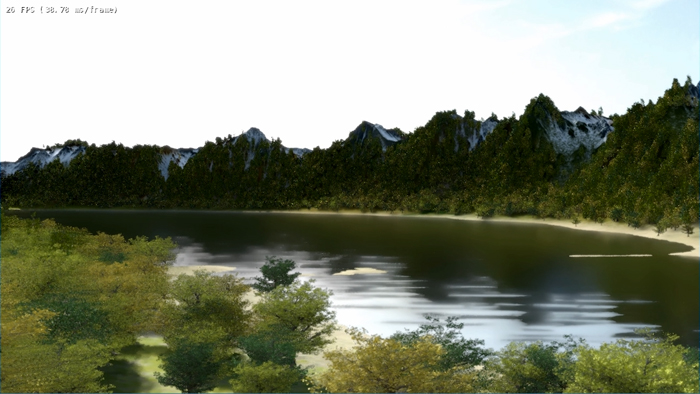

Similar developments are happening in design visualisation. Nvidia has built ‘AI denoising’ into its Optix ray tracing engine. So instead of having to wait for the GPU to compute thousands of passes, it conducts a few passes and then uses deep learning to remove the noise. It essentially gives a best guess as to what a fully resolved image would look like. This technology has already been implemented in Chaos Group’s V-Ray NEXT.

Nvidia is now taking ray trace rendering one step further by actually changing the architecture of its GPUs. AI denoising in V-Ray NEXT works on most modern Nvidia GPUs, but the new Nvidia RTX graphics cards are specifically architected for ray trace rendering. They include three different types of processing cores – RT cores for ray tracing, Tensor cores for deep learning and CUDA cores for shading. Together with software specifically written to take advantage, RTX promises to massively reduce the time it takes to deliver ray traced images. Indeed, Chaos Group has demonstrated this happening in ‘real time’ in Project Lavina. We hope to see commercial applications appear in 2019.

Of course, we can’t expect things to change overnight. It took DS SolidWorks two years to develop its new graphics engine using an API that works with most graphics cards six years old or less. Nvidia RTX demands a change in both software and hardware.

Big transformations like this often need to happen for our industry to truly advance, but the challenges Nvidia faces with RTX adoption are nothing like those of CPU manufacturers looking to introduce revolutionary new technology.

For years, we’ve stored information in bits – either a 1 or a 0 – but quantum computing introduces the notion of qubits, which can represent both 1 and 0 at the same time. By offering multiple states inside the CPU, the technology promises to deliver computers that are thousands of times faster than those currently available and we expect exciting applications for simulation in particular.

While IBM has just unveiled its Q System One, the first commercial quantum computer, to much fanfare, don’t go holding off on your workstation purchase quite yet. A shift in CPU architectures will likely take decades and there’s still plenty of life in the x86 architecture. All eyes are already on Intel’s monster 28-core Xeon CPU, which is due to launch soon, and there’s also AMD’s 64-core Epyc to come.

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to our email newsletter or print / PDF magazine for FREE