In the second of a two part article on Ai image generation and the culture behind its use, Keir Regan-Alexander gives a sense of how architects are using Ai models and takes a deeper dive into Midjourney V7 and how it compares to Stable Diffusion and Flux

In the first part of this article I described the impact of new LLM-based image tools like GPT-Image-1 and Gemini 2.0.Flash (Experimental Image Mode).

Now, in this second part I turn my focus to Midjourney, a tool that has recently undergone a few pivotal changes that I think are going to have a big impact on the fundamental design culture of practices. That means that they are worthy of critical reflection as practices begin testing and adopting:

1) Retexture – Reduces randomness and brings “control net” functionality to Midjourney (MJ). This means rather than starting with random form and composition, we give the model linework or 3D views to work from. Previously, despite the remarkable quality of image outputs, this was not possible in MJ.

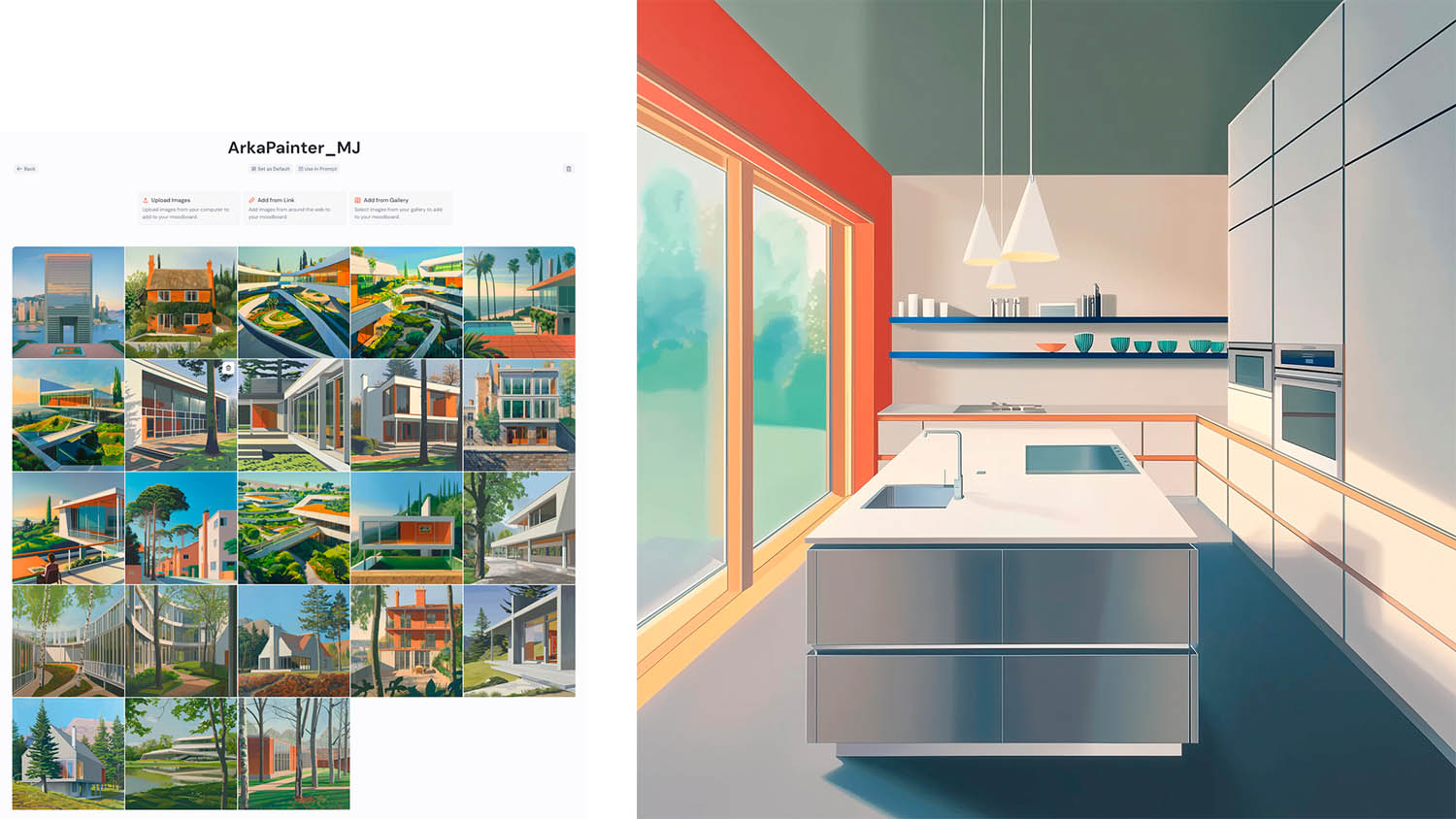

2) Moodboards – Make it easy to very quickly “train your own style” with a small collection of image references. Previously we have had to train “LoRAs” in Stable Diffusion (SD) or Flux, taking many hours of preparation and testing. Moodboards provide a lower fidelity but much more convenient alternative.

3) Personal codes – Tailors your outputs to your taste profile using ‘Personalize’ (US spelling). You can train your own “–p” code by offering up hundreds of your own A/B test preferences within your account – you can then switch to your ‘taste’ profile extremely easily. In short, once you’ve told MJ what you like, it gets a whole lot better at giving it back to you each time.

A model that instantly knows your aesthetic preferences

Personal codes (or “Personalization” codes to be more precise) allow us to train MJ on our style preferences for different kinds of image material. To better understand the idea, in Figure 1 below you’ll see a clear example of running the same text prompt both with and without my “–p” code. For me there is no contest, I consistently massively prefer the images that have applied my –p code as compared to those that have not.

When enabled, Personalization substantially improves the average quality of your output, everything goes quickly from fairly generic ‘meh’ to ‘hey!’. It’s also now possible to develop a number of different personal preference codes for use in different settings. For example, one studio group or team may have a desire to develop a slightly different style code of preferences to another part of the studio, because they work in a different sector with different methods of communication.

Find this article plus many more in the July / August 2025 Edition of AEC Magazine

👉 Subscribe FREE here 👈

Midjourney vs Stable Diffusion / Flux

In the last 18 months, many heads have been turned by the potential of new tools like Stable Diffusion in architecture, because they have allowed us to train our own image styles, render sketches and gain increasingly configurable controls over image generation using Ai – and often without even making a 3D model. Flux, a new parallel opensource model ecosystem has taken the same methods and techniques from SD and added greater levels of quality.

We may marvel at what Ai makes possible in shorter time frames, but we should all be thinking – “great, let’s try to make a bit more profit this year” not “great let’s use this to undercut my competitor

But for ease of use, broad accessibility and consistency of output, the closed-source (and paid product) Midjourney is now firmly winning for most practices I speak to that are not strongly technologically minded.

Anecdotally, when I do Ai workshops, perhaps 10% of attendees really ‘get’ SD, whereas more like 75% immediately tend to click with Midjourney and I find that it appeals to the intuitive and more nuanced instincts of designers who like to discover design through an iterative and open-ended method of exploration.

While SD & Flux are potentially very low cost to use (if you run them locally and have the prerequisite GPUs) and offer massive flexibility of control, they are also much much harder to use effectively than MJ and more recently GPT-4o.

For a few months now Midjourney now sits within a slick web interface that is very intuitive to use and will produce top quality output with minimal stress and technical research.

Before we reflect on what this means for the overall culture of design in architectural practice going forwards, here are two notable observations to start with:

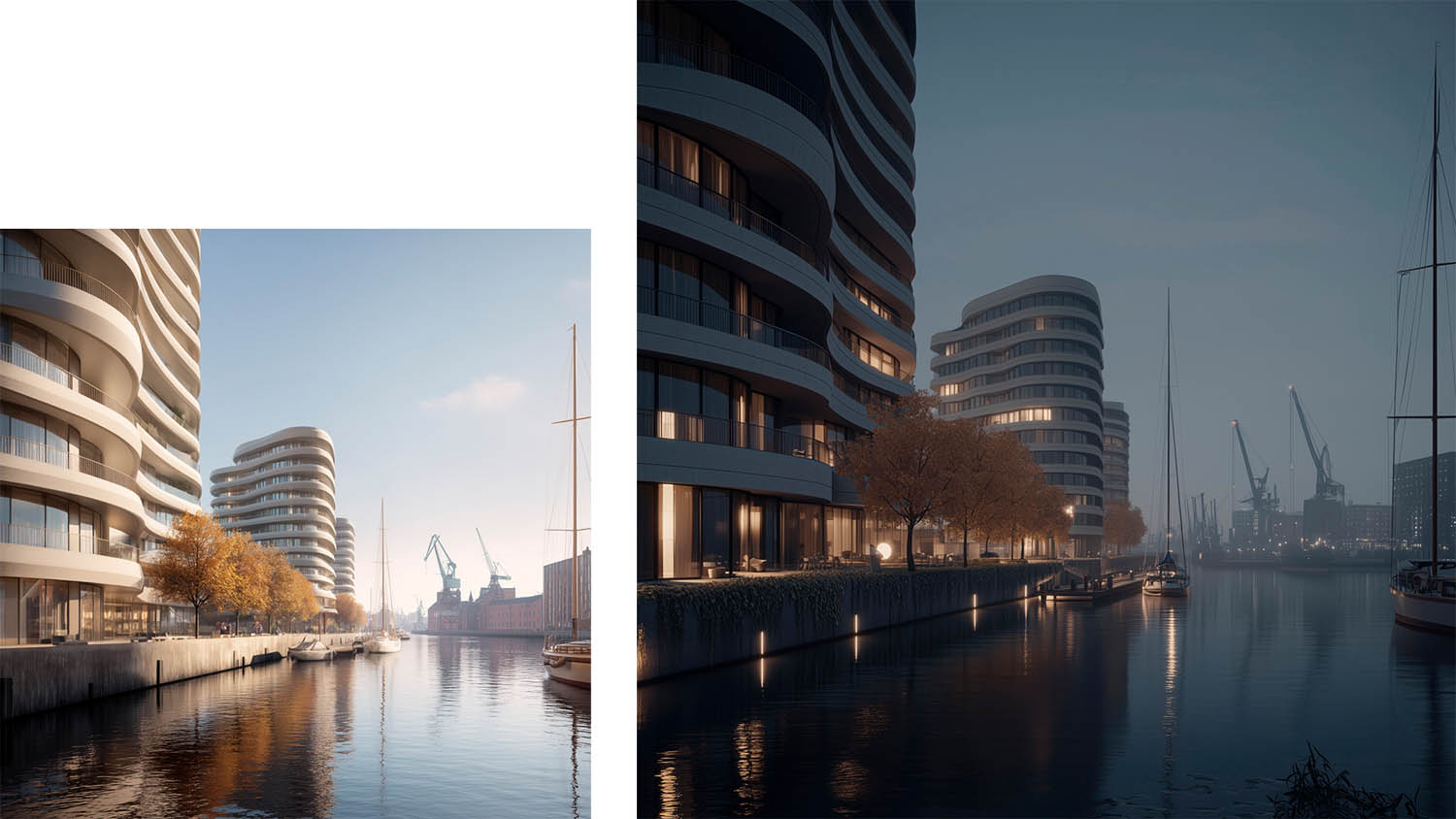

1) Practices who are willing to try their hand with diffusion models during feasibility or competition stage are beginning to find an edge. More than one recent conversation is suggesting that the use of diffusion models during competition stages has made a pivotal difference to recent bid processes and partially contributed to winning proposals.

2) I now see a growing interest from my developer client base, who want to go ahead and see vivid imagery even before they’ve engaged an architect or design team – they simply have an idea and want to go directly to seeing it visualised. In some cases, developers are looking to use Ai imagery to help dispose of sites, to quickly test alternative (visual) options to understand potential, or to secure new development contracts or funding.

Make of that what you will. I’m sure many architects will be cringing as they read that, but I think both observations are key signals of things to come for the industry whether it’s a shift you support or not. At the same time, I would say there is certainly a commercial opportunity there for architects if they’re willing to meet their clients on this level, adjust their standard methods of engagement and begin to think about exactly what value they bring in curating initial design concepts in an overtly transparent way at the inception stage of a project.

Text vs Image – where are people focused?

While I believe focusing on LLM adoption currently offers the most immediate and broadest benefits across practice and projects – the image realm is where most architects are spending their time when they jump into Generative Ai.

If you’re already modelling every detail and texture of your design and you want finite control, then you don’t use an Ai for visualisation, just continue to use CGI

Architects are fundamentally aesthetic creatures and so perhaps unsurprisingly they assume the image and modelling side of our work will be the most transformed over time. Therefore, I tend to find that architects often really want to lean into image model techniques above alternative Ai methods or Generative Design methods that may be available.

In the short term, image models are likely to be the most impactful for “storytelling” and in the initial briefing stages of projects where you’re not really sure what you think about a distinctive design approach, but you have a framework of visual and 3D ideas you want to play with.

Mapping diffusion techniques to problems

If you’re not sure what all of this means, see table below for a simple explanation of these techniques mapped to typical problems faced by designers looking to use Ai image models.

Changes with Midjourney v7

Midjourney recently launched its v7 model and it was met with relatively muted praise, probably because people were so blown away by the ground breaking potential of GPT-image-1 (an auto-regression model) that arrived just a month before.

This latest version of the MJ model was trained entirely from scratch so as a result it behaves differently to the familiar v6.1 model. I’m finding myself switching between v7 and 6.1 more regularly than with any previous model release.

One of the striking things about v7 is that you can only access the model when you have provided at least 200+ “image rating” preferences which points to an interesting new direction for more customised Ai experiences. Perhaps Midjourney has realised that the personalisation that is now possible in the platform is exactly what people want in an age of abundant imagery (increasingly created with Ai).

I for one, much prefer using a model that feels like it’s tuned just for me – more broadly, I suspect users want to feel like only they can produce the images they create and that they have a more distinctive style as a result. Leaning more into “Personalize” mode is helping with that and I like that MJ gating access to v7 behind the image ranking process.

I have achieved great results with the new model, but I find it harder to use and you do need to work differently with it. Here is some initial guidance on best use:

- v7 has a new function called ‘draft’ mode which produces low-res options very fast. I’m finding that to get the best results in this version you have to work in this manner, first starting with draft mode enabled and then enhancing to larger resolution versions directly from there. It’s almost like draft mode helps v7 work out the right composition from the prompt and then enhance mode helps to refine the resolution from there. If you try to go for full res v7 in one rendering step, you’ll probably be confused by the lower-par output.

– - Getting your “personalize” code is essential for accessing v7 and I’m finding my –p code only begins to work relatively effectively from about 1,000+ rankings, so set aside a couple of hours to train your preferences in.

– - You can now prompt with voice activation mode, which means having a conversation about the composition and image type you are looking for. As you speak v7 will start producing ideas in front of you.

Letting the model play

Image models improvise and this is their great benefit. They aren’t the same as CGI.

The biggest psychological hurdle that teams have to cross in the image realm is to understand that using Ai diffusion models is not like rendering in the way we’ve become accustomed to – it’s a different value proposition. If you’re already modelling every detail and texture of your design and you want finite control, then you don’t use an Ai for visualisation, just continue to use CGI.

However, if you can provide looser guidance with your own design linework before you’ve actually designed the fine detail, feeding inputs for the overall 3D form and imagery for textures and materials, then you are essentially allowing the model to play within those boundaries.

This means letting go of some control and seeing what the model comes back with – a step that can feel uncomfortable for many designers. When you let the model play within boundaries you set, you likely find striking results that change the way you’re thinking about the design that you’re working on. You may at times find yourself both repulsed and seduced in short order as you search around through one image to the next, searching for a response that lands in the way you had hoped.

A big shift that I’m seeing is that Midjourney is making “control net” type work and “style transfer” with images accessible to a much wider audience than would naturally be inclined to try out a very technical tool like SD.

I think that Midjourney’s decision to finally take the tool out of the very dodgy feeling Discord and launching a proper new and easy to use UI has really made the difference to practices. I still love to work with SD most of all, but I really see these ideas are beginning to land in MJ because it’s just so much easier to get a good result first time and it’s become really delightful to use.

Midjourney has a bit more work to do on its licence agreements (it is currently setup for single prosumers rather than enterprise) and privacy (they are training on your inputs). While you may immediately rule the tool out on this basis, consider – in most cases your inputs are primitive sketches or Enscape white card views, do you really mind if they are used for training and do they give away anything that would be considered privileged? With Stealth mode enabled (which you have to be on pro level for), your work can’t be viewed in public galleries. In order to get going with Midjourney in practice, you will need to allay all current business concerns, but with some basic guardrails in place for responsible use I am now seeing traction in practice.

Looking afresh at design culture

The use of “synthetic precedents” (i.e. images made purely with Ai already) is also now beginning to shape our critical thinking about design in early stages. Midjourney which has an exceptional ability to tell vivid first-person stories around projects, design themes and briefs, with seductive landscapes, materials and atmosphere. From the evidence I’ve seen so far, the images very much appeal to clients.

We are now starting to see Ai imagery be pinned up on the wall for studio crits and therefore I think we need to consider the impact of Ai on the overall design culture of the profession.

If we put Ai aside for a moment – in architectural practice, I think it’s a good idea to regularly reflect on your current studio design culture by considering first;

- Are we actually setting enough time aside to talk about design or is it all happening ad-hoc at peoples’ desks or online?

– - Do we share a common design method and language that we all understand implicitly?

– - Are we progressing and getting better with each project?

– - Are all team members contributing to the dialogue or waiting passively to be told what to do by a director with a napkin sketch?

– - Are we reverting to our comfort zone and just repeating tired ideas? • Are we using the right tools and mediums to explore each concept?

When people express frustration with design culture, they often refer specifically to some aspect of technological “misuse”, for example;

- “People are using SketchUp too much. They’re not drawing plans anymore”

– - “We are modelling everything in Revit at Stage 3, and no one is thinking about interface detailing”

– - “All I’m seeing is Enscape design options wall to wall. I’m struggling to engage”

– - “I think we might be relying too heavily on Pinterest boards to think about materials”, or maybe;

– - “I can’t read these computer images. I need a model to make a decision”.

… all things I’ve heard said in practice.

Design culture has changed a lot since I entered the profession, and I have found that our relationship with the broad category of “images” in general has changed dramatically over time. Perhaps this is because we used to have to do all our design research collecting monograph books and by visiting actual buildings to see them, whereas now I probably keep up to date on design in places like Dezeen or Arch Daily – platforms that specifically glorify the single image icon and that jump frenetically across scale, style and geography.

One of the great benefits of my role with Arka Works is that I get to visit so many design studios (more than 70 since I began) and I’m seeing so many different ways of working and a full range of opinions about Ai.

I recently heard from a practice leader who said that in their practice, pinning up the work of a deceased (and great) architect was okay, because if it’s still around it must have stood the test of time and also presumably it’s beyond the “life plus 70 year Intellectual Property rule” – but in this practice the random pinning up of images was not endorsed.

Other practice leads have expressed to me that they consider all design work to be somehow derivative and inspired by things we observe – in other words – it couldn’t exist without designers ruminating on shared ideas, being enamoured of another architects’ work, or just plain using peoples’ design material as a crib sheet. In these practices, you can pin up whatever you like – if it helps to move the conversation forward.

Some practices have specific rules about design culture – they may require a pin up on a schedule with a specific scope of materials – you might not be allowed to show certain kinds of project imagery, without a corresponding plan, for example (and therefore holistic understanding of the design concepts). Maybe you insist on models or prefer no renders.

I think those are very niche cases. More often I see images and references simply being used as a shortcut for words and I also think we are a more image-obsessed profession than ever. In my own experience so far, I think these new Ai image tools are extremely powerful and need to be wielded with care, but they absolutely can be part of the design culture and have a place in the design review, if adopted with good judgement.

This is an important caveat. The need for critical judgment at every step is absolutely essential and made all the more challenging by how extraordinary the outputs can be – we will be easily seduced into thinking “yes that’s what I meant”, or “that’s not exactly what I meant, but it’ll do”, or worse “that’s not at all what I meant, but the Ai has probably done a better job anyway – may as well just use Ai every time from now on.”

Pinterestification

This shortening of attention spans is a problem we face in all realms of popular culture, as we become more digital every day. We worry that quality will suffer as people’s attention spans cause more laziness around design idea creation and testing – which would cause a broad dumbing down effect. This has been referred to as the ‘idiot trap’, where we rely so heavily on subcontracting thinking to various Ais, that we forget how to think from first principles.

You might think as a reaction – “well let’s just not bother using Ai altogether” and I think that’s a valid critique if you believe that architectural creativity is a wholly artisanal and necessarily human crafted process.

Probably the practices that feel that way just aren’t calling me to talk about Ai, but you would be surprised by the kind of ‘artisanal’ practices who are extremely interested in adopting Ai image techniques because rather than seeing them as a threat, they just see it as another way of exercising and exploring their vision with creativity.

Perhaps you have observed something I call “Pinterestification” happening in your studio?

I describe this as the algorithmic convergence of taste around common tropes and norms. If you pick a chair you like in Pinterest, it will immediately start nudging you in the direction of living room furniture, kitchen cabinets and bathroom tiles that you also just happen to love.

They all go so well on the mood board…

It’s almost like the algorithm has aggregated the collective design preferences of millions of tastemakers and packaged it up onto a website with convenient links to buy all the products we hanker after and that’s because it has.

Pinterest is widely used by designers and now heavily relied upon. The company has mapped our clicks; they know what goes together, what we like, what other people with similar taste like – and the incentives of ever greater attention mean that it’s never in Pinterest’s best interest to challenge you. Instead, Pinterest is the infinite design ice cream parlour that always serves your favourite flavour; it’s hard to stop yourself going back every time.

Learning about design

I’ve recently heard that some universities require full disclosure of any Ai use and that in other cases it can actually lead to disciplinary action against the student. The academic world is grappling with these new tools just as practice is, but with additional concerns about how students develop fundamental design thinking skills – so what is their worry?

The tech writer Paul Graham once said “writing IS thinking” and I tend to agree. Sure, you could have an LLM come up with a stock essay response – but the act of actually thinking by writing down your words and editing yourself to find out where you land IS the whole point of it. Writing is needed to create new ideas in the world and to solve difficult problems. The concern from universities therefore is that if we stop writing, we will stop thinking.

For architects, sketching IS our means of design thinking – it’s consistently the most effective method of ‘problem abstraction’ that we have. If I think back to most skilful design mentors I had in my early career, they were ALL expert draftspeople.

That’s because they came up with the drawing board and what that meant was they could distil many problems quickly and draw a single thread through things to find a solution, in the form of an erudite sketch. They drew sparingly, putting just the right amount of information in all the right places and knowing when to explore different levels of detail – because when you’re drawing by hand, you have to be efficient – you have to solve problems as you go.

Someone recently said to me that the less time the profession has spent drawing by hand (by using CAD, Revit, or Ai), the less that architects have earned overall. This is indeed a bit of a mind puzzle, and the crude problem is that when a more efficient technology exists, we are forced into adoption because we have to compete for work, whether it’s in our long term interests or not – it’s a Catch 22.

But this observation contains a signal too; that immaculate CAD lines do a different job from a sketching or hand drawing. The sketch is the truly high-value solution, the CAD drawing is the prosaic instructions for how to realise it.

I worry that “the idiot trap” for architects would be losing the fundamental skills of abstract reasoning that combines spatial, material, engineering and cultural realms and in doing so failing to recognise this core value as being the thing that the client is actually paying for (i.e. they are paying for the solution, not the instructions).

Clients hire us because we can see complete design solutions and find value where others can’t and because we can navigate the socio-political realm of planning and construction in real life – places where human diplomacy and empathy are paramount.

They don’t hire us to simply ‘spend our time producing package information’ – that is a by-product and in recent years we’ve failed to make this argument effectively. We shouldn’t be charging “by the time needed to do the drawing”, we should be charging “by the value” of the building.

So as we consider things being done more quickly with Ai image models, we need to build consensus that we won’t dispense with the sketching and craft of our work. We have to avoid the risk of simply doing something faster and giving the saving straight back to the market in the form of reduced prices and undercutting. We may marvel at what Ai makes possible in shorter time frames, but we should all be thinking – “great, let’s try to make a bit more profit this year” not “great let’s use this to undercut my competitor”.

Conclusion: judicious use

There is a popular quote (by Joanna Maciejewska) that has become a meme online:

I want Ai to do my laundry and dishes, so that I can do art and writing, not for Ai to do my art and writing so that I can do my laundry and dishes

If we translate that into our professional lives, for architects that would probably mean having Ai assisting us with things like regulatory compliance and auditing, not making design images for us.

Counter-intuitively Ai is realising value for practices in the very areas we would previously have considered the most difficult to automate: design optioneering, testing and conceptual image generation.

When architects reach for a tool like Midjourney, we need to be aware that these methods go right to the core of our value and purpose as designers. More so, that Ai imagery forces us to question our existing culture of design and methods of critique.

Unless we expressly dissuade our teams from using tools like Midjourney (which would be a valid position), anyone experimenting with it will now find it to be so effective that it will inevitably percolate into our design processes in ways that we don’t control, or enjoy.

Rather than allow these ad-hoc methods to creep up on us in design reviews unannounced and uncontrolled, a better approach is to consider first what would be an ‘aligned’ mode of adoption within our design processes – one that fits with the core culture and mission of the practice and then to make more deliberate use of it with endorsed design processes that create repeatable outputs that we really appreciate.

If you have a particularly craft-based design method, you could consider how that mode of thinking would be applied that to your use of Ai? Can you take a particularly experimental view of adoption that aligns with your specific priorities? Think Archigram with the photocopier.

We also need to question when something is pinned up on a wall alongside other material, if it can be judged objectively on its merits and relevance to the project, and if it stands up to this test – does it really matter to us how it was made? If I tell you it’s “Ai generated” does it reduce its perceived value?

I find that experimentation with image models is best led by the design leaders in practice because they are the “tastemakers” of practice and usually create the permission structures around design. Image models are often mistakenly categorised as technical phenomena and while they require some knowledge and skill, they are actually far more integral to the aesthetic, conceptual and creative aspects of our work.

To get a picture of what “aligned adoption of Ai” would mean for your practice, it should feel like you’re turning up the volume on the particular areas of practice that you already excel at, or conversely to mitigate aspects of practice that you feel acutely weaker in.

Put another way – Ai should be used to either reinforce whatever your specialist niche is or to help you remedy your perceived vulnerabilities. I particularly like the idea of leaning into our specialisms because it will make our deployment of Ai much more experimental, more bespoke and more differentiated in practice.

When I am applying Ai in practice, I don’t see depressed and disempowered architects – I am reassured to find that the most effective people at writing bids with Ai, also tend to be some of the best bid writers. The people who end up becoming the most experimental and effective at producing good design images with Ai image models, also tend to be great designers too and this trend goes on in all areas where I see Ai being used judiciously, so far – without exception.

The “judicious use” part is most important because only a practitioner who really knows their craft can apply these ideas in ways that actually explore new avenues for design and realise true value in project settings. If you feel that description matches you – then you should be getting involved and having an opinion about it. In the Ai world this is referred to as keeping the “human-in-the-loop” but we could think of it as the “architect-in-the-loop” continuing to curate decisions, steer things away from creative cul de sacs and to more effectively drive design.

Recommended viewing

Keir Regan-Alexander is director at Arka Works, a creative consultancy specialising in the Built Environment and the application of AI in architecture. At NXT BLD 2025 he explored how to deploy Ai in practice.

CLICK HERE to watch the whole presentation free on-demand

Watch the teaser below