Towards a new Zeitgeist in architecture

In nineteenth century philosophy, the term Zeitgeist was used by German philosophers to describe “the spirit of the age”. An invisible force dominating the characteristics of a given epoch in world history. Today, AI is promising to bring with it a new Zeitgeist that will change our stream of thought as we enter a new era. However, to unleash its power, we first must first give up some of our core beliefs.

Living in the empiric age

With the rise of computers and algorithms, we have reached an era which I would describe as “the empiric age”. To define it in short: beautiful, romantic, and sacred-out. Functional, optimised, efficient-in. It is an age where rational and functional reasoning is the prism through which we view reality and is the justifier of our decision making. But where does this meet architecture or art? Where does one draw the line between pure rationalism and desirability?

Architecture has always stood at the pinnacle of human ambitions, literally engraving mankind’s epoch achievements in stone. The Greek philosophers sought out for a catharsis – a purification and purgation of emotions through dramatic art and extravagant architecture. In the Middle Ages, the role of architecture was to empower the divine feelings of holiness. The Renaissance put humanism and the beauty of nature in the spotlight and the Futurists of the 20th century sought to worship the machine and the coming of the industrial age.

From a bird’s eye history perspective, over the years we have seen a gradual move from subjective streams of thought based on locality and culture into an objective and universal truth. This was ever so evident in architecture with the move to modernism, which blurred, not to say erased, the boundaries of locality and created a “one-truth-fits-all” approach. The death of the ornament and rise of the function.

AI to the rescue

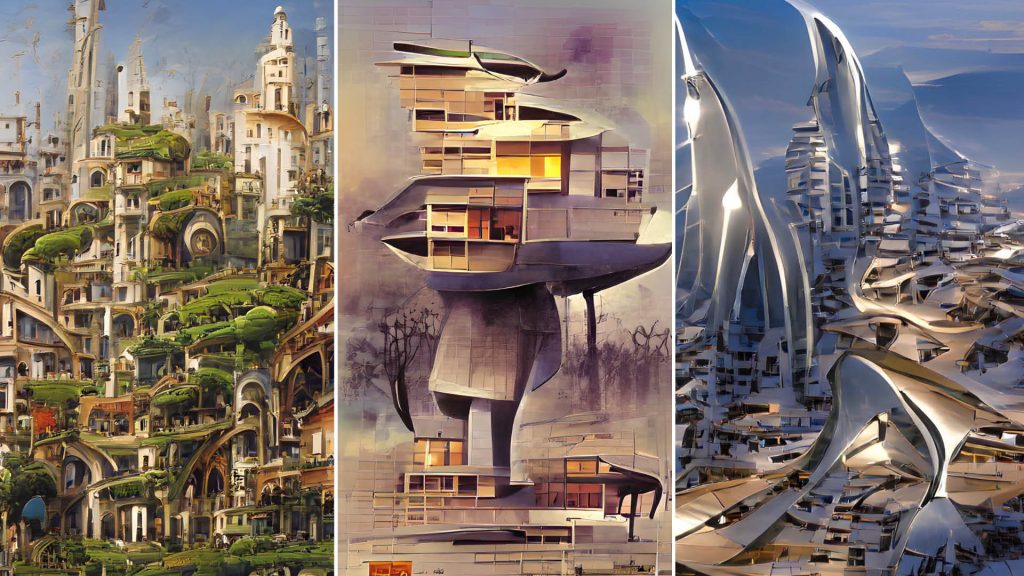

Recent developments in AI have created a completely new standard for what we perceive as “computational” design. Not only can software provide us with a digital design canvas such as Photoshop, CAD sketching or 3D modellers, but, for the first time in history, it can design for us.

Text to image generators such as Dall-E and Midjourney are spreading like wildfire and demonstrating no less than a revolution in how we transform our thoughts into visual reality. However, they also reveal some of the weak spots of our abilities and make us rethink the “human advantage”.

Since the public release of such tools, and due to their ease of use, we are being bombarded with image creations in all fields possible – from children’s books to automotive design and architectural visions. What used to require skilled artists is now just a few letters away. So here is the real question: what is the value of these works?

Where reality stops, art begins – from “creation” to “generation”

A similar question has been posed with the invention of the camera, which pulled the rug under the feet of realist painters. This camera required artists to stop copying reality, as the camera could do a far better job than they could and forced them to give new interpretations to reality which the camera could not. In other words, the camera could only display what was there, but not “invent” reality. The same was deemed true about the computers of our age – “they can calculate, but they can’t think” was the common notion. The new age of AI and machine learning is changing all that. But just like any race car, without a responsible driver it can become a dangerous weapon.

One would expect AI tools to unleash creativity and reveal new and unimaginable layers of artistic value. However, the thing striking me is that most work being published resembles a mockup of reality which could have been produced manually. In fact, they are starting to become remarkably similar to one another, to the point where one can detect them just by their style, especially in the case of Midjourney. It is many times an uncanny and uncomfortable version of reality. This is happening for two reasons:

1. The machine learning process learns from past examples, and therefore creates a mix and match of what has already been defined. It bases its assumptions on things which we have already perceived. Whether there is another option remains a philosophical question.

2. Innovation comes in small chunks. Can we grasp quick changes without getting used to one innovation at a time? This is especially evident in art, architecture, and fashion. We no longer need to wait for styles or trends to “sink in”. We can generate thousands of iterations at the click of a button and accelerate design evolution. Or can we?

Building a new world with AI

Construction is set to become one of the greatest benefiters from the AI revolution. Not only will we be able to release ourselves from the technicalities of drafting and long regulation process, but we will also be able to create better architecture. How? By simply sitting back and letting AI do the work.

If we truly grasp the notion of machine learning, we will let algorithms select not only the “what” but also the “how”. What do I mean by that? In today’s perception, it is us that define the questions and tasks and AI that shoots out answers. As an example, a common AI manoeuvre is “style learning” – learning a style and replicating it in different variations. A Zaha Hadid cupcake, A Frank Gehry wedding dress or, perhaps, a dog resembling a Le Corbusier building (don’t try that at home)? We create the visions and let AI interpret the rest. But if we let AI itself define its goals and only request “amazing architecture” on a plot of land? What if we give up complete authorship and just request things that are determined as “awesome”?

Teaching AI to recognise what makes us tick and raises emotions in us is, perhaps, the next step in human-machine interaction. Removing the A from AI means moving to an age of natural intelligence and giving up control of basic notions of what it means to create. It means exposing ourselves to machine learning and letting algorithms ‘learn us’ rather than learn objects or styles. By doing this, we will be able to discover the undiscoverable. We must learn to understand machines so they can understand us.

Tal Friedman is an architect and construction-tech entrepreneur active in automated algorithm-based design-to-fabrication.