AEC start-ups continue to hit the concrete ceiling, despite the vast potential for digital disruption in the sector. In this article, Tal Friedman proposes a strategy for entrepreneurial success that he believes could help break the pattern and see the rise of the first contech mega companies

The construction industry is one of the largest sectors on the planet. Yet even with an annual value estimated at $14 trillion, it has so far yet to experience digital disruption.

The potential is huge, too, and billions of dollars were invested in construction and property technology (contech and proptech) start-ups over the past five years, with the mission of sparking a revolution in how we create the built environment.

Yet what has been perceived as a field brimming with potential is still to produce the desired fruit. In this article, we will delve into the key challenges facing AEC start-ups and how these might be overcome.

In recent years, I have witnessed first hand the growth of the construction tech industry, through my own involvement in running a start-up, taking on advisory roles for government organisations and corporates, and working in the construction material commerce space. That’s given me an in-depth view of the huge potential here, and how far we are from filling the current gap. I present my views with hope that it can help AEC entrepreneurs and investors find some common ground on which to build.

Find this article plus many more in the May / June 2025 Edition of AEC Magazine

👉 Subscribe FREE here 👈

Why the delay?

So what makes construction so tricky and so seemingly immune to digital disruption as compared to other sectors? As I see it, construction tech start-ups face a number of key challenges, including:

Dinosaurs versus unicorns: Construction is a game that comes with a very heavy ticket price to play. Not only does it require a strong financial backbone and stamina, it also takes a lot of experience – one that cannot be bought, even with lavish funding. As opposed to the IT sector, where new start-ups can spring up to become market-leading mega companies with valuations measured in billions of dollars in just a few years, the building sector is dominated by veterans. Even in the construction software space, the market is led by well-established players offering tech stacks that are often 20 to 30 years old. This would seem like a natural breeding ground for a new age to emerge, where the Canva, Figma or Wiz of construction might flourish, but it is yet to happen. Let’s begin the analysis by seeing how the money is spread.

Construction start-ups are from Venus, venture capitalists (VCs) are from Mars: Traditionally, most VCs come from a software-first mindset, in which success is defined in terms of recurring revenue, user acquisition, and scalable SaaS models. They focus on large user numbers, lean, quick growth and owning categories. In contrast, construction start-ups are rooted in a world of physical infrastructure, where value is created through complex, capital-heavy projects with long lead times, tight regulations, and high execution risk. Even if they are software-oriented, the mindset is completely different, as we will explore later in this article. VCs expect exponential growth curves and monthly churn reports, while construction founders grapple with bidding cycles, procurement hurdles and delivery timelines measured in years, not sprints. This disconnect can make it difficult for construction innovators to translate their impact into metrics that VCs can understand. And that looks set to remain the case, at least until a new generation of investors emerges who are prepared to go deep into the screw level. Some construction tech oriented VCs have emerged over the last years such as Foundaental, Brick and Mortar, Building Ventures, Blackhorn Ventures, Zacua and Kompas. Some leading construction companies also make corporate venture capital (or CVC) available to promising start-ups. These include Cemex, Saint-Gobain and Vinci. However, we still need the ‘heavy lifters’ of the VC world to help scale the field.

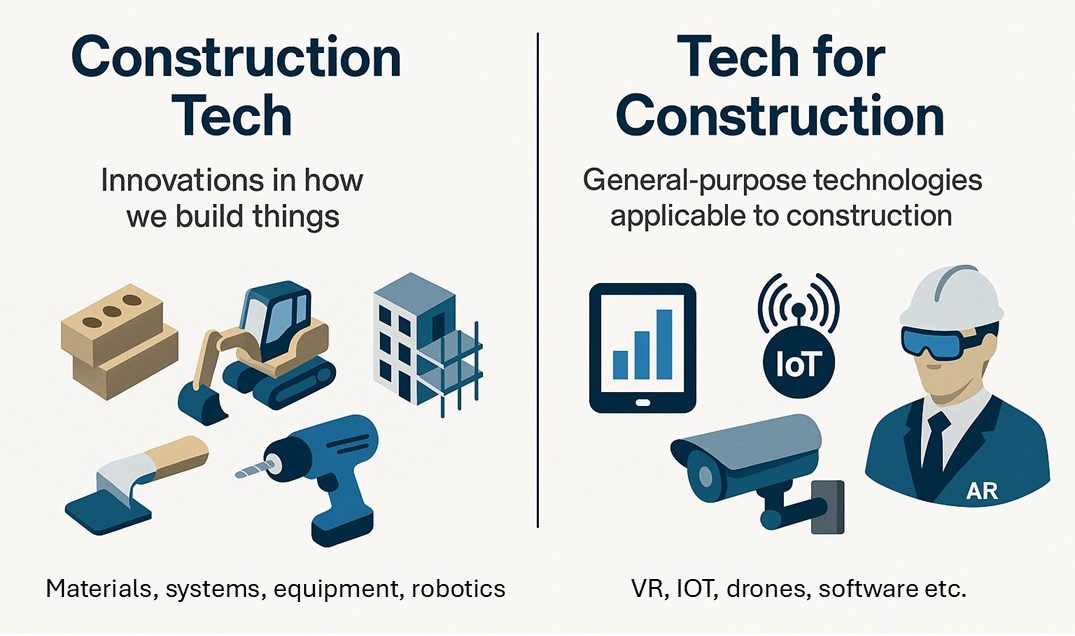

Construction tech versus tech for construction: One of the crucial misconceptions of this market lies in the failure to distinguish between these two verticals. The term ‘construction tech’ refers to innovations in how we build things, focusing on construction processes, materials and methodologies. The term ‘tech for construction’, by contrast, is used to refer to pure technological applications, such as management software, Internet of Things (IoT) technologies, AR/VR and others. In other words, these are technologies that can be applied to construction, but are not specific to the field. But VCs tend to invest in the second category, the pure tech models, seeking the next Uber, Figma, Airbnb, Facebook or Tesla of construction. Their investments aim for disruptive, high-growth technology, but are often disconnected from the ground – or in our case, the building site. Fields like manufacturing, materials, and on-site work have always been less lucrative to tech investors, but this is where the greatest potential for sector-wise change lies.

Warning: hurdles ahead

So what are the biggest hurdles faced by construction tech start-ups? In my experience, the most prevalent barriers include:

1. The ‘butterfly effect’, where risk is greater than gain: In construction, time is money and projects are inherently risky. Each project is unique, involving numerous variables and stakeholders. For a start-up, developing a new solution might be straightforward and worth the risk of trying, but that’s only because they are not paying the price of their mistakes. A minor deviation from the plan can lead to significant delays and cost overruns in completely unexpected areas. The potential risks associated with untested technology are often too great for construction companies to bear. Therefore, start-ups must provide watertight solutions with a clear silo of their work scope that mitigate the risk.

2. Recognition that a one-trick pony is not a unicorn: Despite being a $14 trillion industry, the construction sector is a relatively small market for point solutions. These are specific, narrow applications designed to address particular problems. The number of practicing AEC professionals is estimated at between 3 million and 4 million, which translates to a limited customer base for specialised software solutions. It’s important to note that the AEC software market is valued at around $6 billion, controlled by centralised players. This discrepancy highlights the limited scope and scalability of many construction tech solutions. While a point solution might solve a specific problem efficiently, its applicability is often too narrow to attract widespread adoption to build a unicorn.

3. A monopolised software ecosystem: Due to the heavy nature of the industry, software start-ups face a difficult situation in which they can never replace the existing platforms, but only integrate. Players such as Autodesk, Nemetschek, Bentley Systems are so heavily rooted in the industry that start-ups must adapt their solution to mature infrastructure and formats that are sometimes not at the forefront. Closed formats create a very muddy puddle in which to play, while IFC simply does not provide enough of a format. This rough landing makes it difficult for new entrants to board. Start-ups must fight an uphill battle before even entering the ring. Creating non-intrusive on-boardings that don’t require switching and implementing a long learning curve can drastically improve chances of success

4. The difference between a service and SaaS: The days of software training and specialists are over. In the instant AI age, expecting users to retrain with complex new tools as in the past is unrealistic. With tech solutions popping up like mushrooms after the rain, users lack the skills to go deep and this often creates problems for anyone making a serious construction application. As a result, construction tech companies frequently need to provide comprehensive services alongside their product to tailor fit it and follow through. This service-intensive model can be very heavy and costly not just for the customer, but also for the start-up. Given the ‘plug-and-play’ expectations of the market, start-ups can easily find themselves in a swamp of unprofitable projects that far exceed their initial offering and remain unscalable. It is key to build products that are self-maintained and exercised by the client.

5. Makers developing for makers: A significant challenge in achieving product/ market fit arises when creators design solutions to solve their own problems, rather than addressing broader industry needs. This insular approach often results in products that resonate very much with a niche audience, but fail to gain traction in the wider market. For instance, an engineer might develop a tool to streamline a specific aspect of their workflow, without considering how many professionals face the same issue, or if the solution can be scaled. It may be so that 90% of their colleagues will find it useful, yet there are not enough of them to build a large business, or they can’t afford to pay the required prices. This type of company may be quick to build traction, but that can be very misleading.

6. Lengthy time-to-market: Construction projects often span two to five years. This extended timeline is fundamentally at odds with the rapid growth expectations applied to start-ups and their investors. Start-ups typically need to demonstrate exponential growth and achieve scalability quickly. However, the slow pace of the construction industry means that it can take years for a start-up to complete a real proof of concept (POC), regardless of how much funding it has raised. If a project spans three years, and a new tech is onboarded for trial, it could take a few years before the technology becomes a watertight solution and only then scan it start to scale. This protracted timeline hinders the ability to achieve the rapid growth necessary to reach unicorn status, deterring investors who seek faster returns.

Turning disadvantage to advantage

Having described the hurdles, let’s remember that along with barriers comes potential. The biggest advantage of construction is scale and stability. If it works, it’s huge! Yes, it takes a bit more time, but that time is won back as a competition barrier.

The market has proven that the building sector is one of the safest and most reliable markets for those with a competitive advantage. Start-ups offering true innovation can win big and become unicorns if they have the patience and foresight to understand their path. Seeking quick returns and hyper growth from the get-go is likely to lead to disappointment.

For me, the AEC unicorn formula is:

Onboarding ease * users * profit = Potential

This simple equation provides a quick analysis tool to predict the likely success of startups. It is simply a grading system based on three crucial metrics. Combine these together in the formula, and you will find a useful grading system to evaluate success.

The Unicorn formula for AEC

Onboarding (Grade factor 1-10)

Ease of adoption • Required support • Risks associated

Potential users

Total amount of users or projects. Take 10% of that.

Profitability

Estimated profit per user/project.

Ease of onboarding: This is perhaps the most crucial determiner of a go/no-go situation. As previously mentioned before, there is no time in today’s world for deep training and long integration times. Smooth onboarding and usage is the key to winning customers. This is calculated as a factor between 1 and 10, where 10 indicates the optimum ease of use.

Users: These are users/projects that show potential to become customers. The goal is to identify a realistic number of customers who are willing to pay for the tech product or service and assume 10% of that number will be won over.

Profit: This is a term that isn’t sufficiently talked about in a start-up world where everyone is chasing scale, but construction is a cut-throat business and if your product is not competitive or is just a ‘nice-to-have’ rather than a ‘must-have’, it will not survive. Profit margins should be watertight and based on competitive advantage.

Conclusion

As we step into the age of AI and automation, it is predicted that construction will transform itself, and with it the nature of its tools and the daily lives of its workers.

This is an exciting time in history and an opportunity to get on board. AI is not only being used in the tools that we make – it’s also being used to make them. That’s lowering barriers to entry like never before. For this reason, we can expect to see a big increase in digital solutions from developers of all sizes, opening doors that for years were thought of as closed.

I hope this article helps you position yourself in this brave new world, either as a user, an entrepreneur or an investor looking to take part in the digital transformation of construction. I am certain that if all six points are addressed, success is guaranteed. Best of luck to us all!

Tal Friedman will be presenting at NXT BLD on 11 June – ‘From AI visions to fabricated realities’