Transcend aims to automate one of engineering’s slowest frontend processes – the design of water, wastewater and power infrastructure. Its cloud-based tool generates LOD 200 designs in hours rather than weeks and is already reshaping how some utilities, consultants and OEMs approach projects

The Transcend story begins inside Organica Water, a company based in Budapest, Hungary and specialising in the design and construction of wastewater treatment facilities.

Transcend was a tool built by engineers at Organica to solve the persistent headache of producing preliminary designs for these facilities quickly and at scale. They found traditional manual design processes too limiting, so they put together a digital tool that connected spreadsheets, calculations and process logic in order to automate much of the work associated with early-stage design.

This tool, the Transcend Design Generator (TDG), was a big success at Organica, slashing the time it took engineers to produce proposals and enabling them to explore multiple design scenarios side-by-side.

By 2019, it was clear that while Transcend may have started off as an internal productivity aid, it had matured sufficiently to represent a significant business opportunity in its own right. Transcend was spun off as an independent company, led by Ari Raivetz, who served as Organica CEO between 2011 and 2020.

Find this article plus many more in the September / October 2025 Edition

👉 Subscribe FREE here 👈

Today, TDG is positioned as a generative design and automation solution for the infrastructure sector, targeted at companies building critical infrastructure assets such as water and wastewater plants and power stations. It is billed as accelerating the way that such facilities are conceived, embedding sustainability and resilience into designs from their earliest stages.

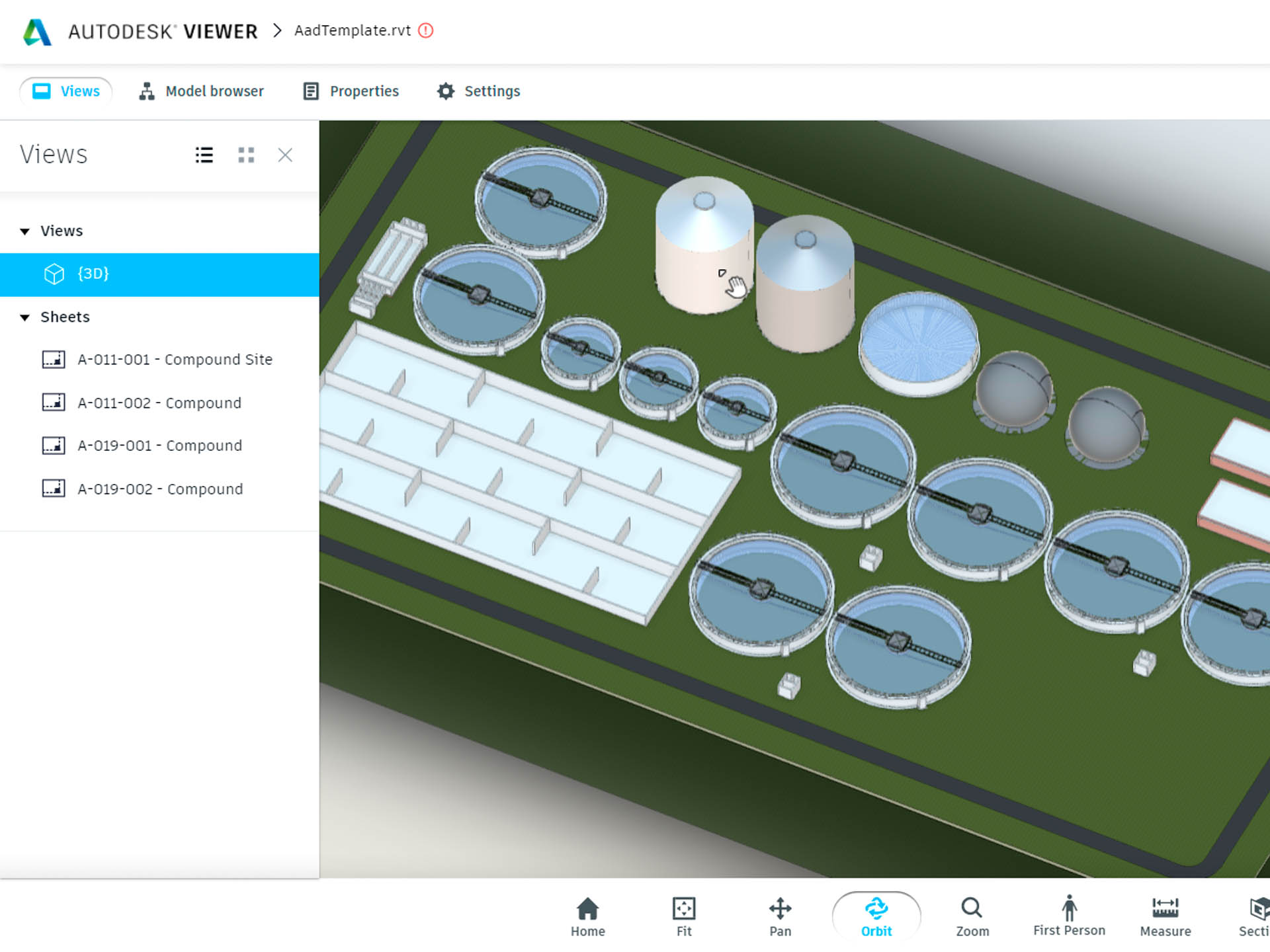

Among Transcend’s strategic partnerships is one with Autodesk, which sees TDG integrated with mainstream BIM workflows, providing a bridge between early engineering and detailed designs. Autodesk is also an investor in Transcend, having contributed to its 2023 Series B funding round. To date, Transcend has raised over $35 million and employs some 100 people globally.

A look at Transcend’s tech

A wealth of capability is baked into the TDG software, which goes beyond geometry generation and parametric modelling to also embrace process engineering, civil and electrical logic, simulation and cost modelling.

Engineers enter a minimal set of inputs, such as site characteristics, flow rates and regulatory requirements, and the tool generates complete conceptual designs that are validated against engineering rules. Outputs include models, drawings, bills of quantities, schematics, cost estimates and carbon footprint calculations. Every decision and iteration is tracked, producing an audit trail that would be difficult to achieve in manual workflows.

The difference compared to traditional design practices is quite stark. With manual conceptual design, weeks of work may yield only one or two viable options, locking in assumptions before alternatives can be properly tested.

Transcend compresses this process into hours, producing multiple design variants that can be compared quickly and objectively. Because the data structures and outputs are already aligned with BIM and downstream processes, the work does not need to be redone at the detailed design stage.

Transcend executives say that using TDG on a project creates a shift from reactive, labour-intensive conceptual engineering to a more proactive approach. The tool, they claim, is capable of delivering part of a typical initial design package, with outputs detailed enough to support option analysis, secure stakeholder approval, underpin bids and provide reliable cost and carbon estimates.

The intent, however, is not to replace detailed design teams. Instead, it is to accelerate and standardise the slowest stage of the workflow, so that engineers can move into the final stage of detailed design with a far clearer, validated baseline.

Impressively transdiscipline

TDG is very much a BIM 2.0 product for civil/infrastructure design and is, at its heart, generative design software.

It uses rules-based automation and algorithms to generate early-stage models, drawings and documentation, solving complex engineering problems through auditable, traceable data, rather than relying on less-reliable LLMs.

All TDG’s processing is on the cloud, so it works without the need of a desktop application and can be accessed from any device with a web browser.

We also find it to be impressively transdiscipline, integrating the design processes of mixed teams to produce complete, multi-option design packages that reflect the work and experience of mechanical, civil and electrical design experts.

This end-to-end, multidisciplinary approach certainly appears to be a key differentiator for Transcend in the automation space.

Q&A with Transcend co-founder Adam Tank

Adam Tank is co-founder and chief communications officer at Transcend. AEC Magazine met with Tank to focus on the company’s Transcend Design Generator (TDG) tool and hear more about its future product roadmap.

AEC Magazine: To begin, we’re curious to know how you define TDG, or Transcend Design Generator, Adam. Is it a configurator, is it AI, is it both – or is it something else entirely?

Adam Tank: TDG is fundamentally a parametric design software. While people often mistake sophisticated autoutomation for artificial intelligence, our software is built on processes that are really thought-out. It operates as a massive parametric solver, similar to tools used in site development like TestFit, but applied to multidisciplinary engineering for critical infrastructure.

We utilise rules-based automation and algorithms to generate complete, viable design options, based on inputs, constraints and standards. TDG can produce designs quickly, by combining first-principles engineering, parametric design rules and proprietary data sets.

Our primary focus is on solving complex engineering problems through auditable, traceable data, rather than relying solely on large language models that might hallucinate. Every decision the software makes can be traced back to a literal textbook calculation or a rule of thumb provided by an expert engineer.

AEC Magazine: So what exactly does the output for a project produced by TDG look like and how deep does the generated geometry go?

Adam Tank: TDG supports the entire early-stage design process. The software is built to follow the same sequential workflow as a multi-disciplinary engineering team, beginning with process calculations, then moving on to mechanical, electrical and civil calculations.

Consequently, it is capable of generating a comprehensive set of validated, reusable data sets and outputs. These outputs include PFDs (process flow diagrams), BOQs (bills of quantities), and full P&IDs (piping and instrumentation diagrams), because it captures all the required data, such as the full equipment list, the geometry, the motor horsepower rating and the electrical consumption of the equipment.

These schematics can be produced in either AutoCAD or Revit. TDG also produces 3D BIM files with geometry generated at LOD 200. This includes key components like slabs, walls, doors, windows, concrete quantities and steel structures. LOD 200 is sufficient for the conceptual design phase, enabling teams to determine the total capital cost of a project within a 10% to 20% margin.

Furthermore, Transcend also generates drawings from the model. Because the model geometry is guaranteed to be accurate through automation, starting from precise specifications rather than attempting to fix poor modelling errors in the drawings, the resulting drawings can be relied upon.

AEC Magazine: So how does TDG effectively combine knowledge and requirements of multiple engineering disciplines into one unified solution?

Adam Tank: The key to TDG is that it functions as an end-to-end, multi-disciplinary, first-principles engineering automation tool. We built the software to follow the exact same sequential thought process that a multidisciplinary team of engineers uses today.

The process begins with the software taking user inputs regarding location, desired consumption, and facility requirements, and combining this with first principles engineering, parametric design rules, and proprietary data sets. Critically, every decision the software makes can be traced back to a textbook calculation or an engineer’s rule of thumb, providing the auditable, traceable data required in this high-risk industry.

The engine then executes the workflow. It starts with the process set of calculations. Once that data is validated, the software transfers that data to the next stage, flowing through a mechanical engine that handles the calculations and then subsequently translating the data for electrical and civil engineering needs.

Essentially, TDG integrates process, mechanical, civil and electrical design logic into one tool, acting as an engine that ‘chews it all up’, from a multi-disciplinary perspective, and produces the unified outputs required by engineers.

This complex system handles local and regional standards, equipment standards and regulatory constraints, guaranteeing that the design options generated are viable and grounded in real engineering standards.

AEC Magazine: The process certainly sounds heavily automated – but where, specifically, does TDG use AI today and what are the company’s future plans for incorporating more AI into the tool?

Adam Tank: Currently, the only part of our software that uses AI is the site arrangement, where we employ an evolutionary algorithm to optimise site layout. When a user inputs the parcel of land and specifications, the software checks constraints and runs through thousands of combinations to determine the optimal arrangement. This algorithm optimises site footprint, while taking into consideration required ingress/egress points for power and water, traffic flow and other necessary clearances.

For future AI development, we are focused on applications that build user trust and enhance productivity. For example, while TDG already produces a preliminary engineering report as part of its output package, we are looking at leveraging AI for text generation within this report.

There’s also scope for an engineering co-pilot. We’d like to integrate an AI-powered co-pilot that guides the user through the TDG interface and, critically, explains the reasoning behind the software’s design decisions. Engineers are accustomed to manipulating every variable manually, so when the computer generates the solution, they need to understand why certain components are placed the way they are. This co-pilot could quote bylaws, manufacturer limitations or engineering standards, effectively allowing the user to query the model itself.

AEC Magazine: How does Transcend handle the complexity of standards and multi-disciplinary data flow across separate but collaborating engineering functions?

Adam Tank: Our software must handle local and regional standards, equipment standards and regulatory constraints, so the amount of data collection is immense.

The complex engine we have built follows the standard engineering workflow. It starts with a user inputting project data, like location, water flow, desired treatment, existing site conditions. This data is used by the process engineer calculation models, which run sophisticated simulations to predict kinetics and mathematics.

TDG acts as the multi-disciplinary engine. It feeds data into those process models, takes the output and then translates it into the next required discipline—mechanical, then electrical, then civil.

This means the engineering itself is still being done, but our engine chews up all the multi-disciplinary requirements and produces the unified outputs that engineers require.

AEC Magazine: Into which markets does Transcend hope to expand next – and why hasn’t the company so far sought to offer higher levels of detail, such as LOD 300 and LOD 400?

Adam Tank: Our focus has been to remain the only company offering end-to-end, multi-disciplinary, first principles engineering automation for critical infrastructure. We don’t have a direct competitor, because our competition is scattered across specialised automation tools that only handle specific parts of the process, such as MEP automation or architectural configuration. We were purpose-built specifically for water, power and wastewater infrastructure, and we are the only generative design software focused entirely on these complex sectors.

Regarding LODs, we have made a deliberate strategic decision not to pursue higher LOD specifications. In the conceptual design phase, we generate geometry at LOD 200. The time and complexity required to achieve that depth would divert resources from attracting new clients and expanding into new conceptual design verticals.

If it were entirely up to me, the next big market we would pursue is transportation, covering roads and bridges, which represents a massive market in terms of total design dollars spent, eclipsing water and wastewater by almost double.

We also get asked a lot about data centre design. This expansion is technologically feasible for us. For instance, early in our company history, we developed a similar rapid configuration tool for Black & Veatch to design COVID testing facilities during the pandemic. We see a potential natural fit with companies like Augmenta, which specialises in electrical wiring automation, where we could automate the building structure and they could handle the wiring complexity.