The chasm between architectural and fabrication design software creates challenges for firms wishing to go beyond the boundaries of traditional documentation. Martyn Day looks at how three pioneering firms — SHoP Architects, Bouygues Construction and WSP — are bridging the divide

The AEC industry has a reputation for being slow to adopt technology. Some reports even place it behind farming. The reality is, while construction has lagged, design has been on an inexorable path to total digitisation since the 1980s.

3D modelling, the adoption of BIM and innovation in digital fabrication is ultimately going to lead to modern methods of manufacturing buildings.

This is not just a technology play; it’s borne out of necessity. The construction industry lacks skilled labour, many economies desperately need new housing, historic poor productivity needs to be addressed. Furthermore, everything from the design, material choice, and location to the fabrication of buildings needs to reflect the carbon climate challenges that will only become more prescient.

Today’s BIM tools add width to the chasm that separates design from fabrication, as they were created to deliver scaled drawing sets, not detailed 3D models for fabrication

To connect the digital thread, this industry needs new tools, new workflows, new fabrication methodologies. In short, and to coin an overused phrase, we need to rethink construction.

However, it’s not just construction that needs rethinking – it’s everything from what we design, through to how it’s fabricated, and how it’s assembled. We need to rethink AEC.

Buildings should be designed in the full context of how they will be fabricated, broken down into assemblies and a ‘Kit of Parts’. Today’s BIM tools add width to the chasm that separates design from fabrication, as they were created to deliver scaled drawing sets, not detailed 3D models for fabrication.

Find this article plus many more in the July / August 2024 Edition of AEC Magazine

👉 Subscribe FREE here 👈

When one tries to add that level of detail, the models swell in size and become unusable. Autodesk has arguably done the most to try and connect BIM and manufacturing CAD, but this has taken years and many attempts to get right.

The current solution boils down to proxy swapping of predefined components between BIM software Autodesk Revit and mechanical CAD (MCAD) software Autodesk Inventor, which lends itself to working with a ‘Kit of Parts’ mentality. This solution, while innovative, is a partial ‘band aid on a bullet wound’, trying to overcome the integration limitations of two products that were never intended to work together.

Those who follow the offsite construction market, will know that it has become a bloodbath in the US and UK. Many fabs have shut down. It’s all too easy to find examples of how not to do it, rather than ones that are making it work. But this time of failure will pass, and lessons will be learnt.

The convergence of design and manufacturing in AEC is going to be an ongoing experiment and it’s going to need some projects that require scale to prove out. This is happening, but it’s not necessarily joined up. The future is everywhere, it’s just not evenly distributed.

At AEC Magazine’s NXT BLD and NXT DEV last month we brought together some industry change makers, who presented the projects and processes that they are refining to connect architecture to construction and deliver digital design to fabrication. Dale Sinclair from WSP, Antoine Morizot from Bouygues Construction and John Cerone from SHoP Architects were three that stood out, taking us from London to Paris to New York.

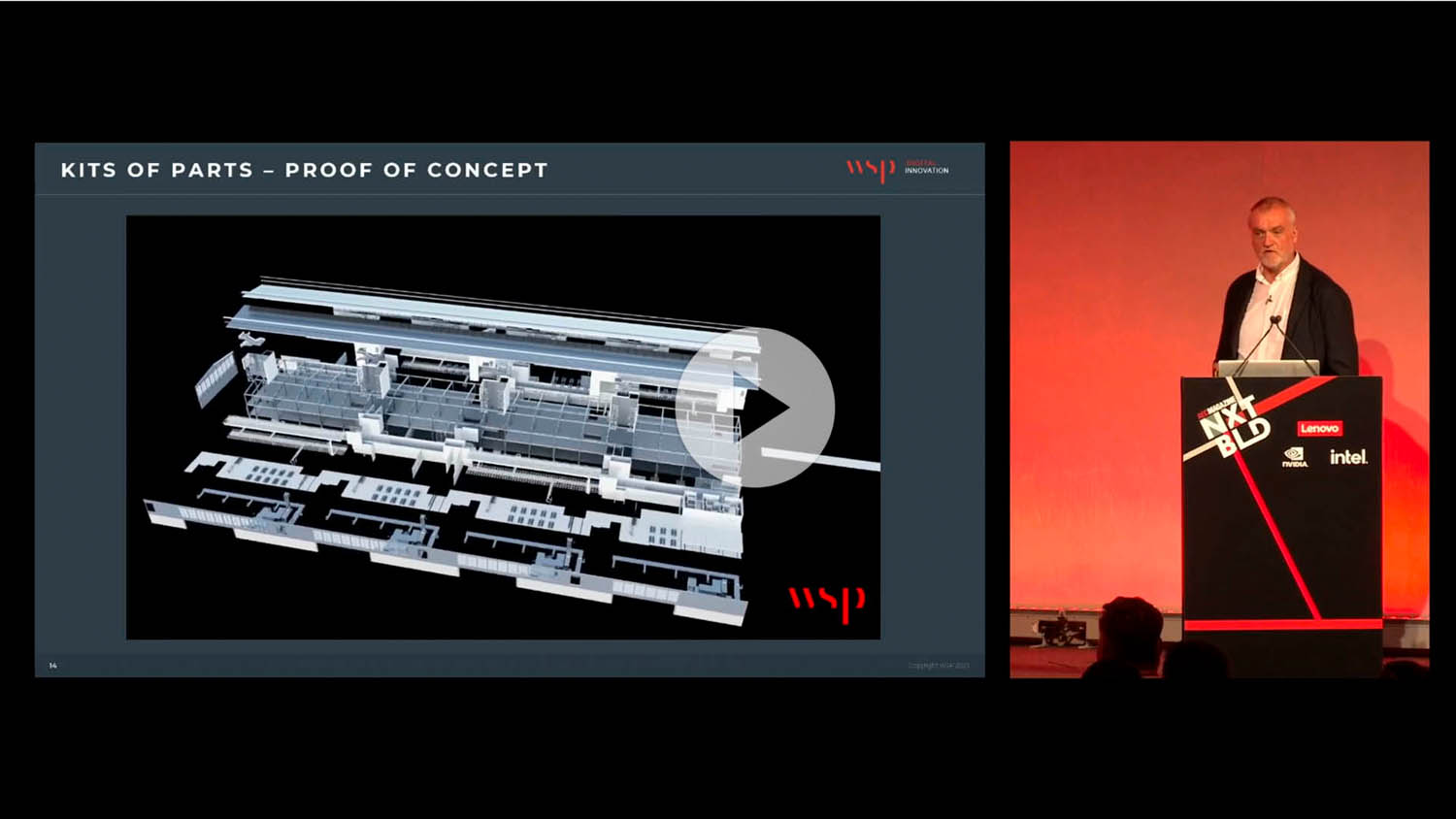

WSP – London

Dale Sinclair first started experimenting with design at 1:1 construction detail level while at AECOM. At the time AECOM was working closely with offsite fabrication firms and Sinclair wanted to ‘talk the same language’ as the fabricators. He eschewed Revit for architectural design on modular projects, and instead adopted Inventor to take an assembly approach.

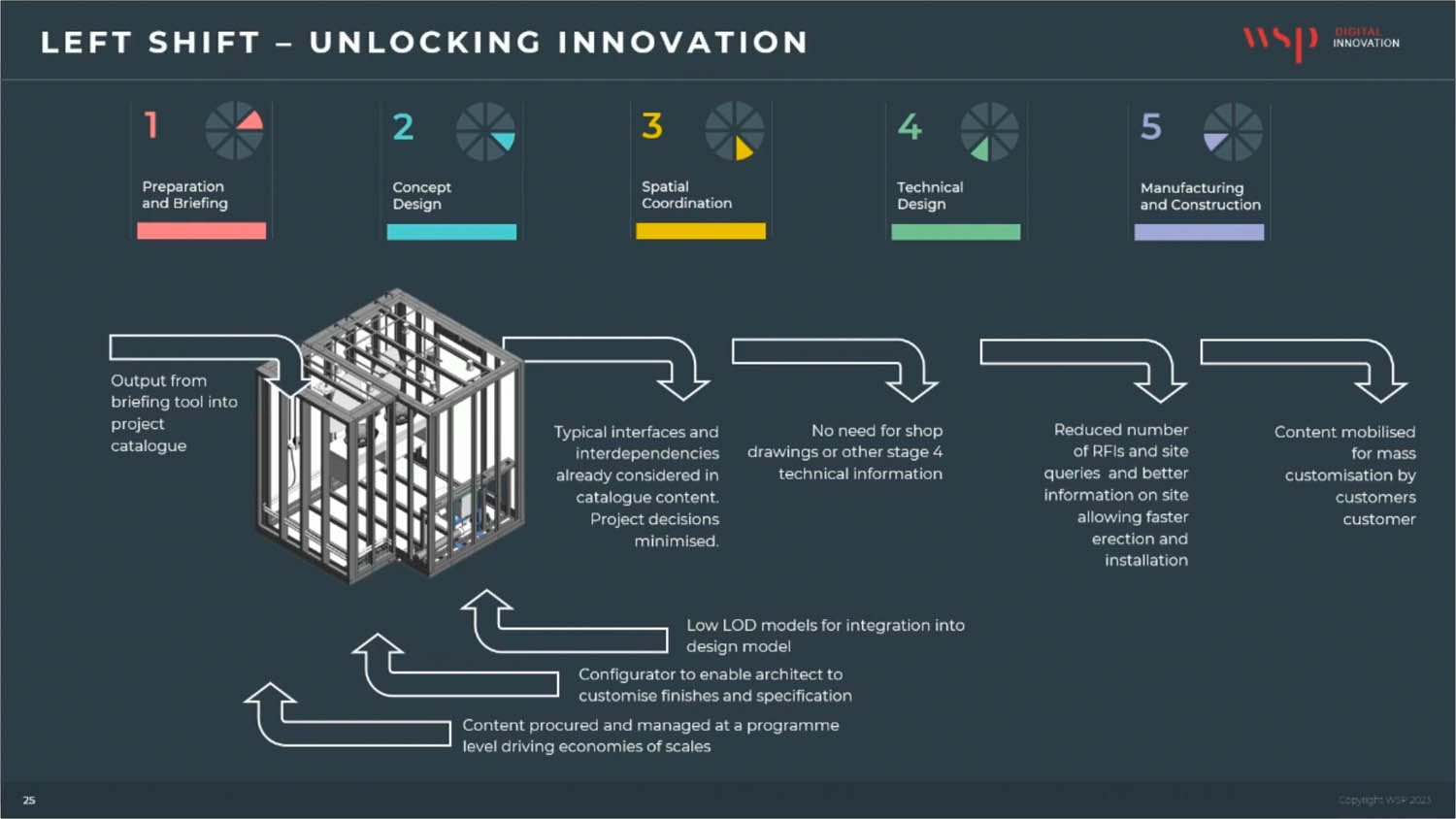

Now at WSP, Sinclair has continued his research into the convergence of construction and manufacturing, developing new processes and looking at the whole workflow from the construction end of the telescope, bringing ‘systems thinking’ to design.

At NXT BLD, he pointed out, “Construction in its current form, cannot continue, because we have all tried but we haven’t moved the dial. We haven’t reduced the cost. We haven’t reduced the time to deliver buildings. The quality is variable, and productivity is static.

“How do we change? We keep putting things together that have never been put together before. The number of new systems are increasing, adding complexity.

“We should be using offsite manufacturing. There is no downside to using factories. We have better safety, bring in more diverse people and get the benefits of scale. We should be leveraging the benefits the manufacturing sector has had for years. But the one thing we have not cracked with offsite is cost and this prevents us from scaling up offsite.”

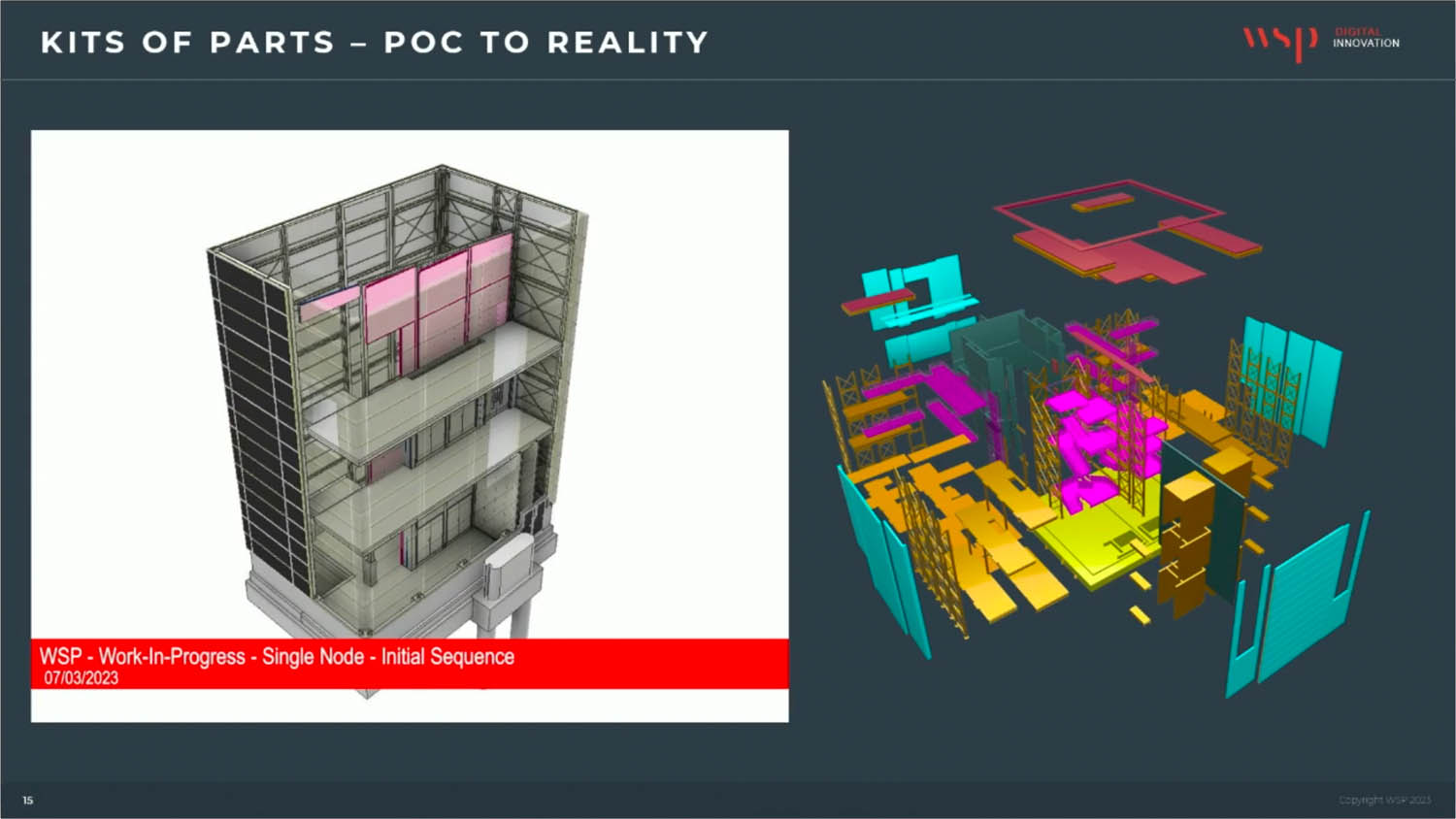

Sinclair explained that adopting a ‘Kit of Parts’ approach in design is phase one. The next step is to mobilise offsite, by taking a small number of large components to site (panelisation not modular).

This can then be followed by adopting a broader ‘program mentality’, using fabrication-level details at the start of a project, pushing manufacturing information upstream and adopting configurators. “We have flipped the entire process on its head, so we are coming from a manufacturing first [approach] and it’s a game changer,” he said.

Sinclair believes off-site has to be explored at a country level. He thinks that offsite fabrication spaces should be distributed throughout the UK, in all the places there is unemployment, and hopes the UK Government wakes up to the benefits of doing something like this. I suspect we will have to wait to see it work somewhere else first.

Watch Sinclair’s NXT BLD talk here

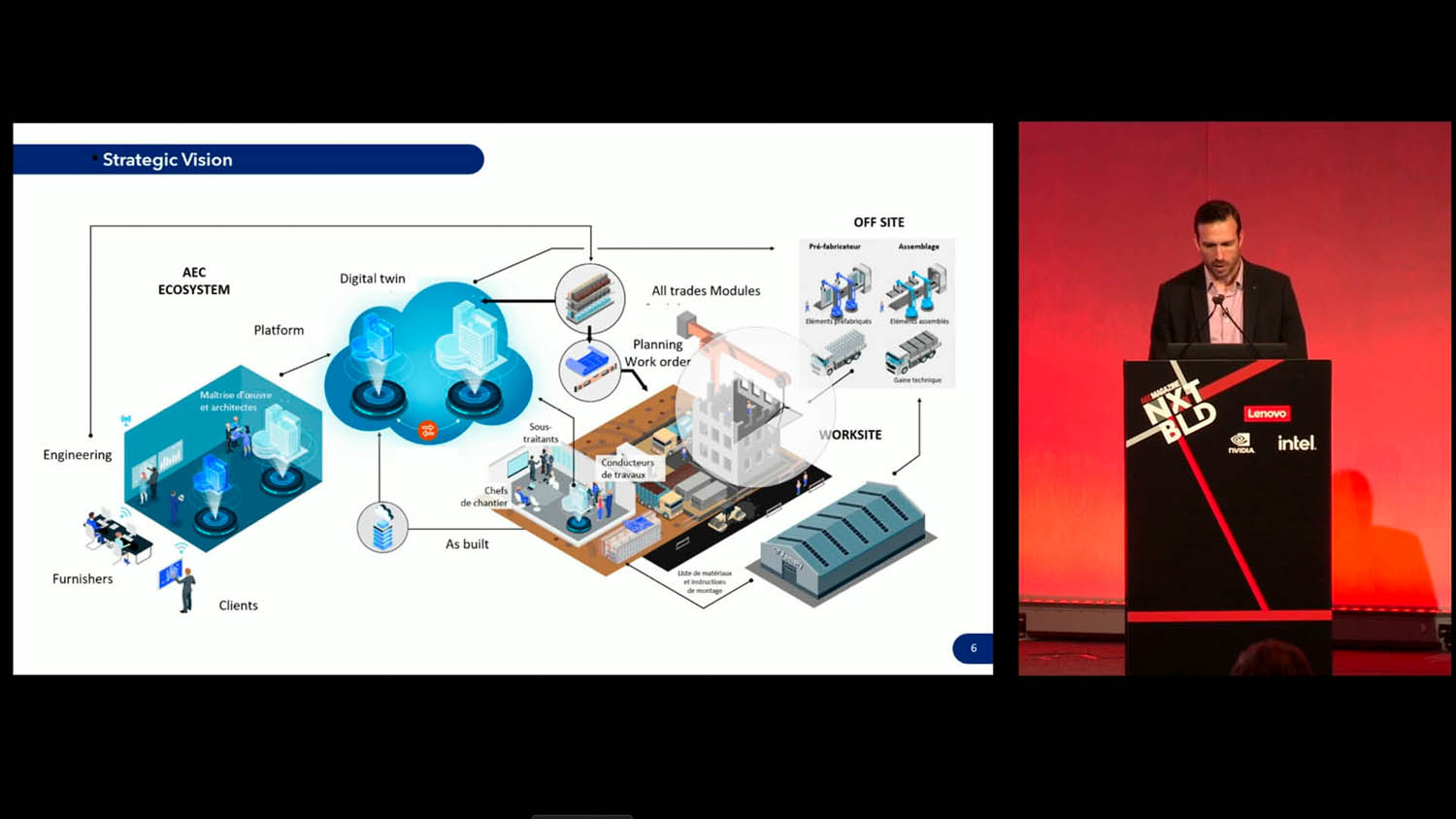

Bouygues Construction – Paris

From the other side of the channel, construction giant Bouygues Construction has been on its own digital journey. It has similar challenges, but instead of focusing on the original architectural design, it concentrates on how to connect its clients’ design information to the Bouygues fabrication and cost estimating system.

The decision to digitise and automate has led to a multi-year consultancy engagement with Dassault Systèmes – creator of the leading MCAD brands Catia and Solidworks – to create an expert system for Bouygues called ‘Bryck’.

Bouygues’ strategic vision is to head towards metamorphosing building sites to a place where products are assembled – unlike the current process, which requires the onsite transformation of materials. Antoine Morizot of Bouygues explained, “The products could have been prefabricated or assembled in micro factories near the site, but the idea is not to standardise the products, it’s to standardise the processes.”

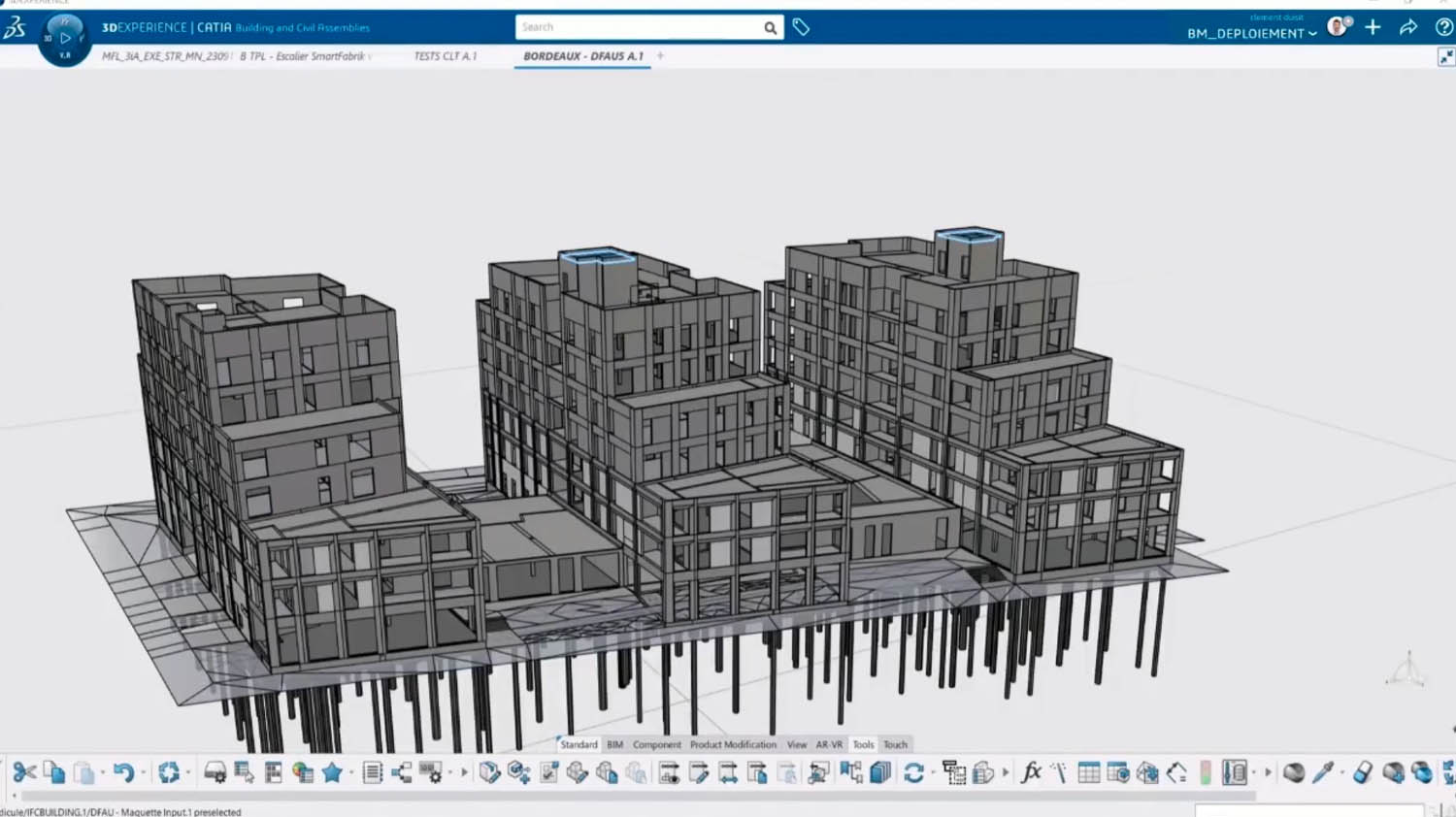

The concept that Bouygues is adopting is not dissimilar to the ones which Dassault Systèmes has proven many times in the manufacturing space for aerospace and automotive. Here customers build a virtual digital mock-up or in common CAD parlance, a digital twin, which contains all the details of what is to be manufactured, to simulate the method of construction, the construction site and the as-built.

Morizot stated that BIM has failed to give the result the industry was expecting. By modelling in 3D, there was an expectation that, like in MCAD, this data could be connected to fabrication systems. BIM data conveys the idea, but not from an engineering or construction point of view. To achieve this, Bouygues has built a ‘productised’ system which covers all these bases, using Catia and customisation to produce a predictable, systemic view of project data.

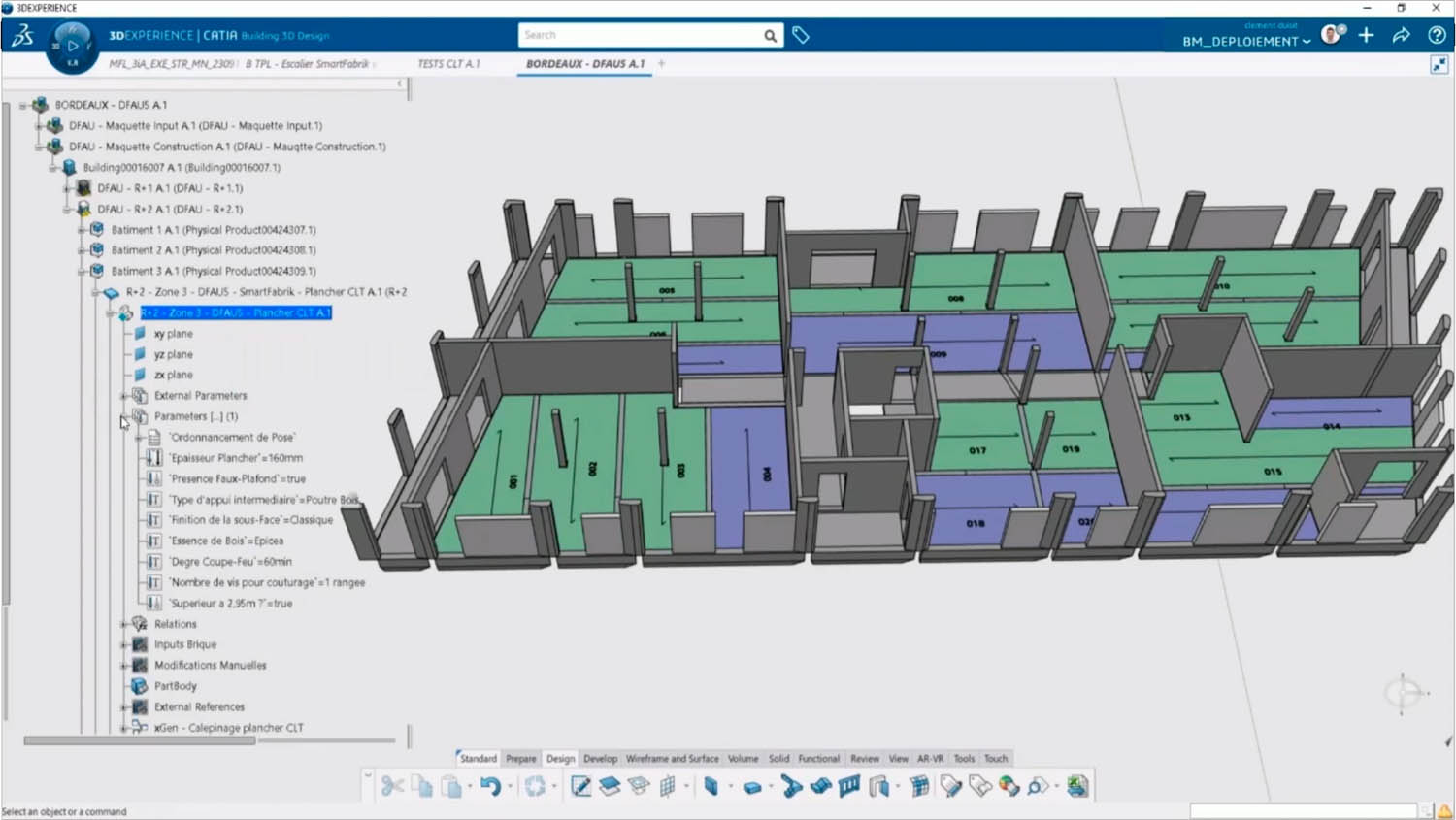

RVT or IFC models are brought in and converted to productised Catia components such as groundwork, structure, covering, partitioning, finishes, MEP, equipment and prefab modules.

This template-based system also offers a library of parametric templates, which pre-define multi-disciplinary parametric modules for central cores, CLT floors, façade design, electrical components, MEP etc, which can adapt to any complex geometry, or imported IFC or Revit files. These ‘products’ adapt to the architectural model, through the use of generative design, adding tags, attributes, dimensions, 3D annotations, surface treatments, manufacturers’ catalogue part numbers, integrating a lot of data making calculations, and even defining the installation order.

Morizot demonstrated that by simply clicking on the raw geometry of a floor in a model, Bouygues can apply a product, in this case a CLT floor, and a complete, highly detailed CLT floor is created, adapting to the new model, ready panelised to fit the capabilities of Bouygues’ in-house fabrication machines. These can then be edited in multiple ways, such as orientation and installation order.

This was a rare outing for Bouygues to explain the level of detail it has achieved with its construction expert system. It means the firm can be given an IFC or a Revit model and in minutes get a fabrication level digital twin, with the exact cost and all the fabrication drawings. Bryck has impressed the company’s board so much that another long-term deal has been signed with Dassault Systèmes, with more capabilities to come.

Watch Morizot’s NXT BLD talk here

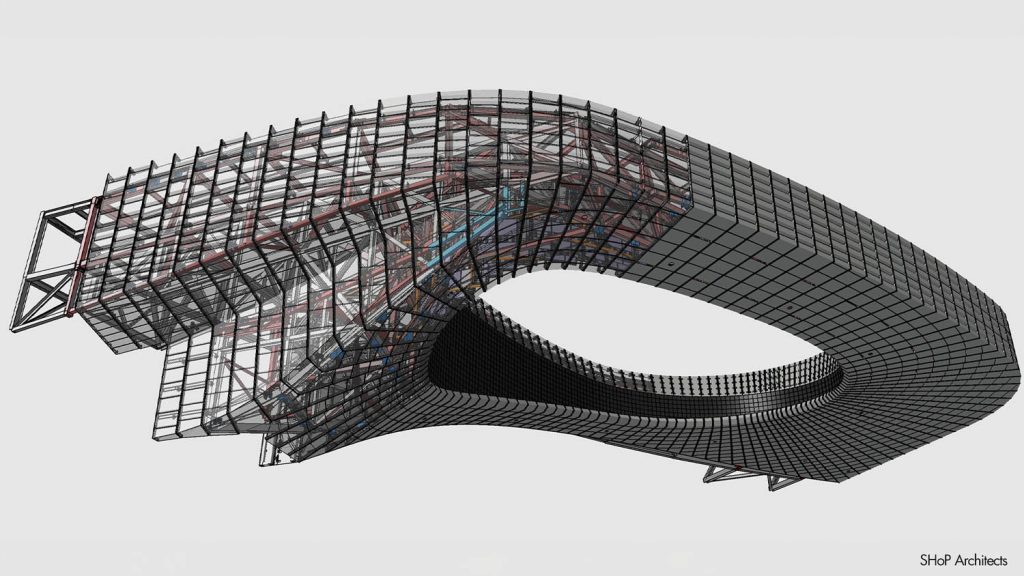

SHoP Architects – New York

New York-based SHoP Architects is a relative latecomer to the NXT BLD roster, but principal John Cerone has been a long-time advocate of embracing digital fabrication and going beyond the limitation of delivering drawings.

Cerone is certainly in the architectural camp of wanting to get rid of drawings and move to a pure modelling paradigm and the practice is doing its utmost to define its own process to connect architecture with modern methods of construction. He defines his firm as ‘Production Architects’ as they focus on materials, process and how the buildings they design are made.

Cerone is on board with offsite manufacturing and the concept of a ‘Kit of Parts’, sub-assemblies and how these Cover story work in the design as a whole. SHoP is not a fan of the plan, section and elevation approach to define its schemes but places itself in the Ikea approach to communication.

Cerone stated, “Architecture, with a capital A, can be designed and manufactured. To do that, you need to understand the processes, who/what is reading the instructions and how the materials are being processed. When you do that, the deliverables are not the flat orthogonal drawings, we can be much more diagrammatic.

“We operate in this industry with the mentality that there’s an opportunity to leapfrog and take advantage of advanced manufacturing techniques in our projects. If you come to our office in downtown Manhattan, in the Woolworth Building, the first thing you’ll notice will be model planes, boats, cars – they are everywhere.

“And for us, one of the principles behind that, is how you can design simulate, coordinate, execute a complex project in a digital format. To do that, you have to get outside of the traditional tools of the AEC industry.”

SHoP Architects is a big fan of Rhino and Catia and builds a lot of its own tools for geometry solvers which are used at scale. The firm has cut its teeth working on projects with complex geometry that were built off site. This involved talking with manufacturers at the concept stage to start optimising for fabrication.

Information, such as optimal steel sheet size helps reduce waste, lower cost, and act as design constraints early on in the process. This means the final design does not need reengineering once all the work is done. SHoP then makes reuseable templates for the assemblies it creates.

From this, SHoP has got heavily into the fabrication side of things, sometimes bypassing the drawing phase and even just delivering the model and the G-code, whilst keeping track of job tickets through factories. On site the firm uses laser scanning to ensure the assemblies are to specification and communicates installation through screen shots of the model.

With all this experience in offsite and manufacturing, SHoP Architects creates a ‘cousin’ company called Assembly OSM to deliver modules for high-rise residential buildings (12 to 30 floors), all based on templates for building systems, including mechanical.

Watch Cerone’s NXT BLD talk here

Conclusion

There are no off-the-shelf solutions to link digital architecture to digital fabrication. Every firm that has made progress connecting the two worlds has done it through belief, investment, experimentation and sheer bloody-mindedness. However, it doesn’t mean that this situation won’t change as lessons learnt by these pioneers will eventually find their way back into features in standard software. The use of Inventor and Catia for defining architectural design is currently niche but there is a chance that next generation BIM tools will have the underlying technologies required to span the design to fabricate chasm.

Defocussing from technology solutions for a moment, it’s clear from Sinclair, Cerone and Bell – all architects – that to wholly embrace the process, the industry needs to start thinking about the design of buildings differently.

If designs are to flow from concept to construction, the ‘Kit of Parts’ approach appears to have the longest legs, mimicking automotive and aerospace. But this still puts a lot of work upfront to design flexible parts with construction-level detailing. As Sinclair points out, less project think and more of a program mentality, spanning projects. Bell has done this with the Facit Homes’ adaptable chassis (see below), where every house is a variation on a tried and tested theme.

Facit Homes – bringing the factory to the construction site

Bruce Bell has a long connection with AEC Magazine and NXT BLD. His UK company Facit Homes uses vanilla Revit with its own family of parts, which are optimised to create highly defined BIM models. Through a secret sauce, they are flattened and G-code is created to fabricate on-site via a router in a shipping container.

In a way, Bell has developed his own expert system that is designed for houses out of mainly one material, that is cut up on site and nailed together to make box sections. Every building created for individual clients is a variation on a long-tested system.

With a deep central resource database of the common products used in fitting out, Facit can predict the cost of its buildings within 1%. As the company also manufactures and assembles the building, that reduces risk and means the company’s fee spans design, construction and delivery. What is incredible is that this all done with off-the-shelf software.

Recently Bell has raised his aim and is looking to develop a giant robot which can cut and stack enough panels to build out entire estates. His talk at NXT BLD highlights the journey he has been on and the solution that he will be bringing to market, which features an onsite micro-factory.