What role will architects play in an AEC industry increasingly intrigued by design for manufacture and assembly (DfMA) approaches? AEC Magazine puts the question to ‘Prefab Queen’ Amy Marks, EVP of Symetri USA

It should come as no surprise to anyone that the woman whose ‘Queen of Prefab’ channel on YouTube has attracted over 9 million views and 9.8k subscribers is a big believer that productisation holds the key to a more efficient and sustainable construction industry.

Amy Marks is now flying the flag for industrialised construction as executive vice president of global strategy at Symetri, a major provider of technology and consultancy services in the US and Europe, which she joined in September 2023. She moved there after some threeplus years at Autodesk, first heading up the software giant’s industrialised construction strategy and later taking on an enterprise transformation role.

Attending her first Autodesk University since leaving the firm, AEC Magazine caught up with Amy Marks and got the opportunity to discuss with her a question that we know preys on the minds of many of our readers. How can architects get on board with productisation?

It’s a tricky question, Marks agrees – but it’s not one without answers, she adds, pointing to her experience of helping architecture clients to think in new ways about what they might otherwise be inclined to consider an existential threat.

The issue, she continues, is that architects are inclined to see prefabrication in construction as a trend that will limit their involvement in design, rather than freeing them from more mundane work and allowing them to focus on big creative challenges that really test their talents.

Data-driven design decisions

But to achieve that kind of freedom, architects looking to succeed in an AEC world increasingly moving towards design for manufacture and assembly (DfMA) will need to make some fundamental shifts in the way they think about data.

Right now, according to Marks, architects are highly dependent on the data of other companies in the AEC sector. “If you think about it, architects don’t make anything. They’re representing what needs to be made, but they don’t actually have what I call ‘the data of make’,” she says.

What they need is to work with tools that automatically provide them with the ‘make’ information for specialised areas of a building – a medical headwall in a hospital, for example, or the hot aisle containment system in a data centre.

It’s simply not reasonable to expect every architect to master the complexities of such structures. Nor is it desirable that firms should rely heavily on the expertise of a member of staff who has mastered the complexities of just one of those structures.

“So what I’m interested in is getting product decision information into the hands of architects – and for that to happen, architects need to be open to the fact that they’ve got to consume this make information in its most efficient form and utilise it so that they can stick to necessary rules and constraints,” she says.

For the architect, they become the designer of the parameters of physical parts of a building. They might not be drawing a fire escape anymore, but who wants to do that anyway?

She likens this to how product lifecycle management (PLM) software is used by product designers in the manufacturing world. “This is standard in manufacturing, but there we see metadata and configurators, things we don’t really have in the AEC space.”

In other words, productisation in construction isn’t just about productising a physical object, but also the metadata and rules associated with that physical object, “almost like it lives in a little data backpack all the time, along with a reference to its LCA entry.”

This information, in turn, would enable architects to search for the right physical part, available for on-time delivery and at the right cost, and with the appropriate environmental credentials and carbon footprint, she reasons. And when an architectural design was delivered to a contractor, they would be alerted if a particular component was no longer available, requiring respecification on the part of the architect.

The technology that could underpin this kind of process already exists today, says Marks, but it hasn’t typically been used this way. But it could enable an evolution of the architect’s way of working, without any significant detour from the fundamentals of good design.

“For the architect, they become the designer of the parameters of physical parts of a building, right? They might not be drawing a fire escape anymore, but who wants to do that anyway? Instead, they will use data from makers to set the parameters of what’s needed, based on their interpretation of the needs of a building’s owner and end user. Now, that’s a different job from the one they perform today, but that ability to set parameters is where a lot of the value will lie in the future state.”

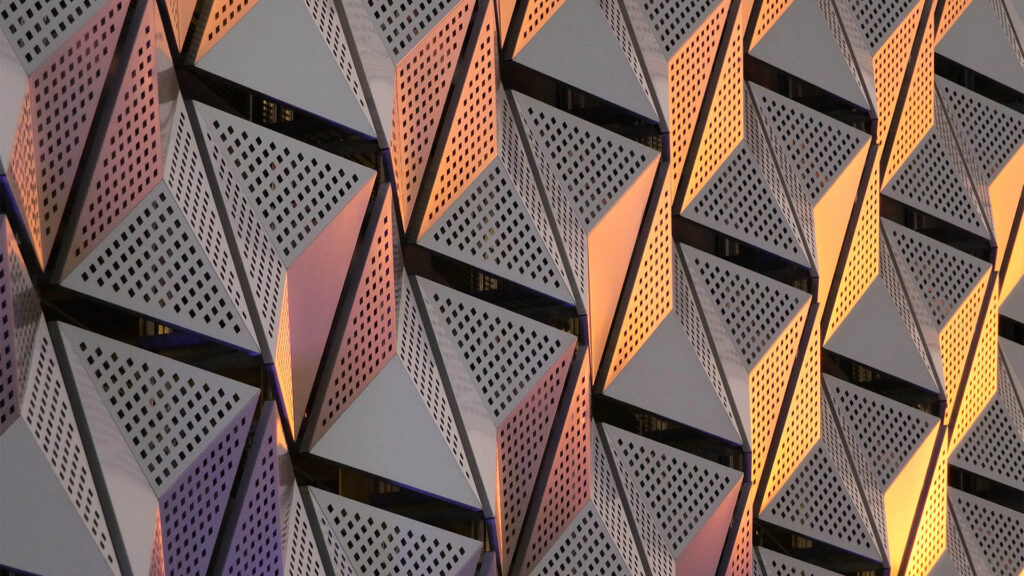

And when it comes to higher order prefabrication, such as facade panels, architects retain their role as lead designers, bringing flair to the job of conceiving and procuring modular components that fit the needs of the project.

Find this article plus many more in the January / February 2024 Edition of AEC Magazine

👉 Subscribe FREE here 👈

Think different

It’s a message that many architects may not be ready to hear. In fact, it’s one with which many might actively disagree. Either way, says Marks, we are a long way off from any building being totally designed along these principles. The elements that can be productised in many buildings account for maybe 5% of their totality.

Marks refers to these as ‘known’ elements. “And we already see in architecture today how we work with ‘known’ elements. For example, in the case of a complicated curtain wall, an architect will typically bring a specialist curtain wall manufacturer in from day one, right? You bring in the guys that specialise in complicated equipment or elements.

In the productisation world, the architect will have a wealth of make information about ‘known’ elements to help them in their design work,” she says.

In the meantime, most buildings are still majority made up of ‘unknown’ elements that architects will continue to define from scratch. “So my message to architects is, ‘Don’t worry.’ There’s still plenty of ‘unknowns’ that need to be designed and there probably always will be,” says Marks.

“But at the same time, architects need to recognise that productisation through prefabrication is happening now. Either they can control their destiny and figure out how best to use their time and how to charge for the things that matter – their ingenuity, their creativity in designing bespoke areas, the real artistry. But to do that, they’ve got to let go of some of the stuff that isn’t art, the stuff that’s mundane, the stuff that’s boring.”

And what creative mind wouldn’t want that as their end goal?

Main image: For higher order prefabrication, such as facade panels, architects retain their role as lead designers