Comvert, the alternative fashion company that makes clothing for skateboarders and snowboarders under the ‘Bastard’ brand took on an ambitious project to turn its Milan headquarters into an indoor skate bowl. By Brett Duesing.

When alternative fashion company Comvert looked into a new space for its Milan headquarters, it came upon a vacant cinema from the 1940s. The movie theatre had enough square footage for design offices, warehousing, and its flagship retail store. The building also had volume — 6,600 cubic metres of vaulted space above the old audience seating. This gave room for a more unusual amenity.

“The idea of building a indoor skate bowl has been around ever since we started Bastard 15 years ago,” says Claudio Bernardini, founder and CEO of the company. Bastard is Comvert’s internationally recognised brand of clothing and accessories for skaters and snowboarders. “The cinema site gave us a real chance to make it happen.”

Milan architects Studiometrico executed a massive, multi-level renovation to the cinema, but Comvert kept the Bastard Bowl as an internal project. “The moment we found the space, we began planning our own design. We wanted the whole project to follow a DIY ethic,” says Mr Bernardini, who was surprised at the extent of the community effort; armies of skaters from around the region showed up to volunteer at every phase of construction.

Perhaps most unique about Comvert’s attic-level skate park was the advanced 3D modelling techniques and digital manufacturing methods — the same ones Comvert used to make snowboard gear. “We wanted cutting-edge structure in terms of the technologies used to design and build it.”

Bastards doing architecture

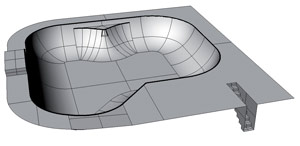

Comvert designers had advised several local municipalities on what goes into a ‘rad’ skate park, so the Comvert team knew exactly they wanted for the shape and features of the course. They conceived of a double-kidney shaped bowl, 1.85 metres deep with two top hips and a lower love seat. Skate bowls originated as empty swimming pools made of concrete, but since the Bastard Bowl would occupy the upper vault of the theatre, Comvert had to take a lighter-weight approach with wood frame construction.

Mr Bernardini had prior experience building a wood track, building parts by hand or with a jigsaw. This time, however, the team wanted to sidestep traditional building process all together.

“As forward-thinking digital designers, we chose to use Rhinoceros instead,” he says. The team had designed the majority of their snowboard and related hardware in the 3D Nurbs modeller, so they were familiar with the capabilities of the software to model parts with complex surfaces that they could easily export to high-precision digital manufacturing.

“We can break the Rhino model down into individual components and send the geometric data for each unique part to CNC cutting machines,” says Mr Bernardini. By the end, CNC workstations had sawed every member and panel of the design, with every piece precisely matching the curves in the 3D model.

Vertical challenges

Once the Rhino model of the Bastard Bowl was completed, Mr Bernardini showed it to Marco Clozza of the local engineering firm Atelier LC. He asked Mr Clozza to calculate the structural requirements, devise a railing system and support from the floor, and then manage the assembly on site.

“Claudio gave me a surface that was ideal for skaters but for builders, not so much,” jokes Mr Clozza. At first, the site itself presented Mr Clozza with a number of challenges. The wooden bowl would rise 25 feet above the lower level, where Comvert had now placed aisles of warehouse shelving. The auditorium-style seating of the old theatre meant a ground floor was not level, but inclined, terraced at points into multiple levels after renovation.

“The design became more complex since we lacked a continuous plane to support the wood frames. Initially, I had no idea how to attach the structure to the warehouse level,” explains Mr Clozza. “But after taking a look at the latest in wooden bowls, we came up with the idea to introduce steel elements, which would not only enhance the look, but it would make it easier to connect to the shelving level. It solved the issue of protective parapets along the edge.”

Because scaffolding would block employees’ access to active shipping and receiving, he borrowed a solution from another Milanese pastime, rock climbing. Mr Clozza would swing from a harness across cinema space during assembly. Mr Clozza used similar contraption of carabineers and climbing rope, nicknamed the Bastard Crane, to lift the CNCed parts to their proper place.

Phat flattening

After a skeletal frame took shape above the warehouse, attention turned to the skating surface. Using an early release of a new Rhinoceros plug-in called Advanced Flattening (en.wiki.mcneel.com/default.aspx/McNeel/AdvancedFlattening.html), Mr Bernardini and Mr Clozza could translate surfaces curved in two directions into flat cookie-cutter patterns for an automatic router.

“The biggest problem was the double radius of curvature of the panels,” says Mr Clozza. “According to the material and thickness, there was a maximum degree of bending we could do to fit it securely to the base structure without breaking.”

At first, Mr Clozza used the Rhino plug-in to panelise the surface as interlocking polygons, like a football. After Mr Clozza’s trial installation on to the frame, they found a three-to-four-millimetre gap between the bent plywood — too big of a crack for smooth skating. The team then went back to the drawing board and chose a simpler geometry for the panels. “We found that panels with straighter lines gave the maximum dimension to curve the plywood in two directions,” says Mr Clozza.

“After several tests, we came up with the final solution that made the spaces less than one millimetre between the panels,” adds Mr Bernardini. “This was the key feature for obtaining a perfect flowing effect.”

Curves for the community

After its unveiling last year, the Bastard Bowl has attracted legions of skate fanatics around the region to Bastard’s flagship store. It now regularly hosts demonstrations from visiting professional skaters, as well as skate parties for Comvert staff and customers.

For Mr Clozza, the project was his first experience with digital manufacturing. “Absolutely it’s the future of construction,” he says. Work on the Bastard Bowl has inspired him to put digital curves in other wood projects, which can be seen on his blog (www.atelier-lc.com), along with the full photographic story of building the ultimate Italian skate track.

The Comvert team discovered that digital manufacturing of product design can easily be applied to large-scale architectural structures. “Modifications and adjustments during the work were very few, so assembly went quickly,” says Mr Bernardini. “This project proved to be an experimenting ground for materials and assembly techniques, even for the most experienced on our team. Individual experiences and contributions gave birth to a collective work that belongs to all of us.”