Pete Baxter, Northern European sales director, Autodesk Building Solutions Division, looks at the ways 3D CAD images can be used beyond the design department and how they can significantly enhance customer service.

I recently heard a story about a small Chinese company working on global projects. As the team didn’t speak much English, they were asked how they communicated with their international partners. “This is our language, now,” they said, pointing at 3D models of their designs on their computer screens.

With the rise of the electronic transfer of data via email or over the internet, the increase in the number of pan-global projects and the growing acceptance of building information modelling, cultural and language barriers become irrelevant. In 3D design software, at last we have technologies that earn their living by improving productivity and helping to create, manage and share.

They say that seeing is believing and it is true that being able to visualise the end building as an integral part of the design process is a huge benefit. It can help communicate ideas to customers eager for a glimpse of what they are getting for their money and to planners keen to assess how a building will sit in a particular landscape.

But of course the important thing about 3D design is that it produces not a picture, but a model holding all relevant information within it. So we are not only sharing images, however powerful these may be, but valuable, accurate data held on a single building model.

Design information is now our lingua franca

For example, the large worldwide practice Wimberley Allison Tong & Goo (WATG) has recently adopted this way of working. The team creates a single, integrated building information model and then shares this information with clients and team members across the world. “I have 600 – 700 users throughout the world, working on close to 70 projects,” Jim Grady, WATG CAD manager, told us.

" Brunton Boobyer and Croft Goode have discovered that a rendered 3D model helps smooth the path with the planners and even credit it with helping them get plans passed quicker "

The multidisciplinary firm RTKL has done a similar thing: “It has changed the dynamics of the project team,” says Heidi Stemkoski, a RTKL designer. “People aren’t so isolated working on just plans, sections or elevations. It’s just not possible to work that way anymore. The team understand the building as a whole – and that’s better for the project.”

But maybe it is the client – whether this is the building end user or property owner – that we ought to consider first. There will always be a place for high-end visualisation and animation to communicate an intended end result. There is no doubt that the stunning and realistic images these produce have the “wow factor” that can help sell a major development or similar heavyweight project.

However, architects must carefully consider the degree of realism actually needed. When you produce a sketch nobody expects the finished building to look just the same. However, when you show a photorealistic image, clients can regard this as a statement of intent, which can set expectations as to how the final scheme will actually look even though many design decisions have yet to be made.

What is needed is a practical compromise; a rendered model that can be used day to day as a design tool, especially if you want to show changes and work “on the fly” while sitting with a customer.

Consequently, the latest 3D software gives visualisation and rendering tools back to the architect so visualisation no longer has to be a drawn-out specialist task but a relatively quick and available process.

As David Davison, UK CAD manager at RTKL explains: “Visualisations are now much easier because, as the building model is being developed, we are able to generate a rendered perspective from the same design file. Therefore, when the client wants to view the finished development, it’s a simple process.”

This works well for smaller practices too. The London-based firm Brunton Boobyer was under increasing pressure to provide such visualisations to customers and had tried several 3D solutions. However, it found that using these there was still the need to produce a separate set of drawings running parallel with standard 2D information. This made the production of illustrations time-consuming and expensive.

However, director, Simon Boobyer, solved this by using a solution where a 3D rendered model is created as an integral part of the design process. Instead of having one visualisation set in time, they can now generate a realistic and understandable model at any stage of the process.

Lancashire architectural practice Croft Goode uses the same solution for all RIBA Plan of Work Stages A to L. This allows them to actually design alongside clients and building users from the outset. “This enables all involved to see and understand the spaces and relationships between building elements clearly,” says John Bridge, architectural technician.

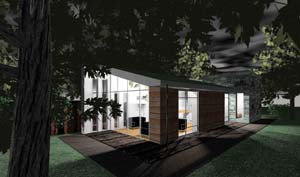

Both these firms have discovered that a rendered 3D model helps smooth the path with the planners and even credit it with helping them get plans passed quicker. One of Brunton Boobyer’s projects was a single-storey house of contemporary design situated in a conservation area.

“On paper this would have set alarm bells ringing for the planners,” says Boobyer. “But we could show exactly how the property would look and fit into its immediate surroundings.”

Chris Tweddle of father and son firm Tweddle Associates tells a similar story: “The planning authority had originally refused a ú1 million barn conversion because they believed it would spoil the neighbouring properties’ view.

" Through graphical visualisation, architects and building services engineers can reference each otherÝs designs to ensure co-ordination and minimise conflicts between disciplines "

“By providing an accurate image of the respective elevations of the proposed conversion and adjacent properties we were able to show that this was not the case. Planners respond positively and it speeds up the process of consents significantly.” He recalls that in this particular case the faster completion not only meant that Tweddle got paid quicker – it also meant that the houses sold at the top of the market.

Sales and marketing teams have reacted favourably to 3D models too. The images are readily available to use in Powerpoints, brochures and to illustrate tender documents, providing a cost-effective alternative to photography.

Better coordination between disciplines

All these advantages certainly improve communication and customer relationships – but perhaps the main gains in productivity come where the technology helps to translate the architect’s ideas to other designers and engineers further along the line. Through graphical visualisation, architects and building services engineers can reference each other’s designs to ensure co-ordination and minimise conflicts between disciplines.

For example, Autodesk Revit Building users can quickly change their architectural design to provide accurate background information for the engineers using Autodesk Building Systems and vice versa. Autodesk Revit Structure, released in the UK in early 2006, will further improve communication in the multidisciplinary design team by extending to structural engineers.

To see how this is working, we need to move to what is probably the most high-profile building project in the world at the moment – the Freedom Tower in New York. Here, JB&B, the project’s building services engineers first worked with Autodesk Consulting to use Revit to develop generic building systems modelling content. This has improved co-ordination with all disciplines as work is carried out in 3D on a plasma screen in the architects’ (Skidmore Owings & Merrill) conference room!

CSG, the structural engineer, used Revit and AutoCAD to model the tower’s foundations and existing buttress slabs, core walls and columns on the original design. The firm is now implementing Revit Structure for use on the design and construction documentation of the new design concept. Once again this is helping translate ideas between the different professionals on the project.

Each discipline within the AEC industry has been a bit like the British themselves; proud of the idiosyncrasies of their own language and reluctant to try to communicate in any other way. But the pressure to increase profit margins means we can no longer afford this luxury.

A central building model can lead to closer communication, greater understanding and enhanced co-ordination. Which means better buildings and increased success – in any language.