In AEC, AI rendering tools have already impressed, but AI model creation has not – so far. Martyn Day spoke with Greg Schleusner, director of design technology at HOK, to get his thoughts on the AI opportunity

One can’t help but be impressed by the current capabilities of many AI tools. Standout examples include Gemini from Google, ChatGPT from OpenAI, Musk’s Grok, Meta AI and now the new Chinese wunderkind, DeepSeek.

Many billions of dollars are being invested in hardware. Development teams around the globe are racing to create an artificial general intelligence, or AGI, to rival (and perhaps someday, surpass) human intelligence.

In the AEC sector, R&D teams within all of the major software vendors are hard at work on identifying uses for AI in this industry. And we’re seeing the emergence of start-ups claiming AI capabilities and hoping to beat the incumbents at their own game.

However, beyond the integration of ChatGPT frontends, or yet another AI renderer, we have yet to feel the promised power of AI in our everyday BIM tools.

The rendering race

The first and most notable application area for AI in the field of AEC has been rendering, with the likes of Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, Dall-E, Adobe Firefly and Sketch2Render all capturing the imaginations of architects.

While the price of admission has been low, challenges have included the need to specify words to describe an image (there is, it seems, a whole art to writing prompting strategies) and then somehow remain in control of its AI generation through subsequent iterations.

In this area, we’ve seen the use of LoRAs (Low Rank Adaptations), which implement trained concepts/styles and can ‘adapt’ to a base Stable Diffusion model, and ControlNet, which empowers precise and structural control to deliver impressive results in the right hands.

For those wishing to dig further, we recommend familiarising yourself with the amazing work of Ismail Seleit and his custom-trained LoRAs combined with ControlNet. For those who’d prefer not to dive so deep into the tech, SketchUp Diffusion, Veras, and AI Visualizer (for Archicad, Allplan and Vectorworks), have helped make AI rendering more consistent and likely to lead to repeatable results for the masses.

However, when it comes to AI ideation, at some point, architects would like to bring this into 3D – and there is no obvious way to do this. This work requires real skill, interpreting a 2D image into a Rhino model or Grasshopper script, as demonstrated by the work of Tim Fu at Studio Tim Fu.

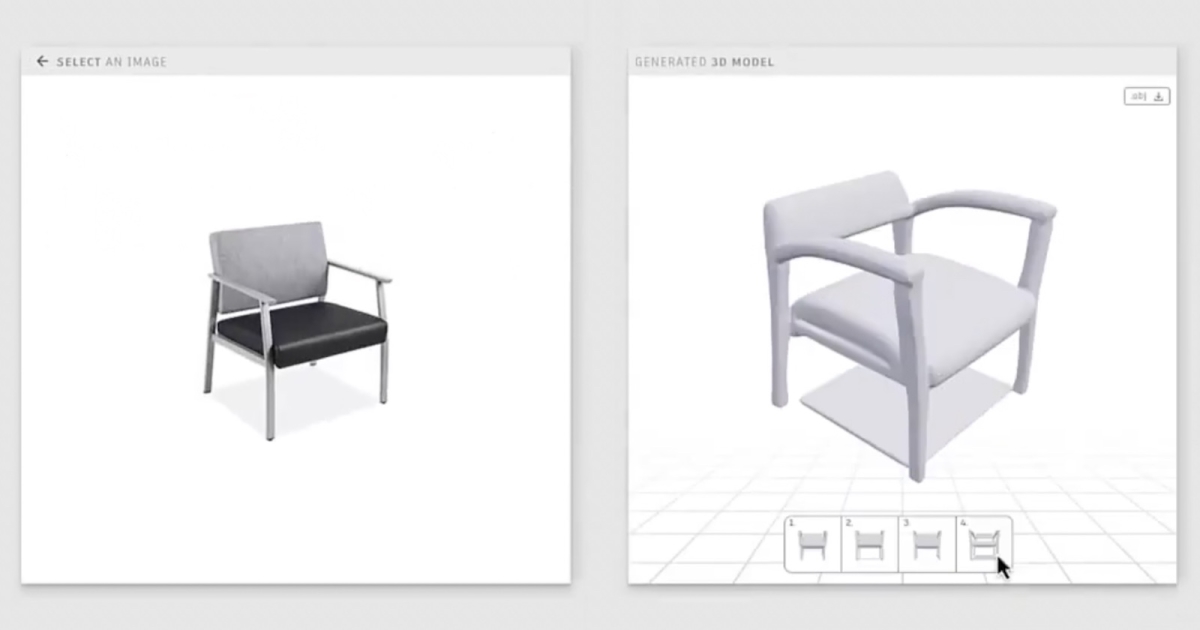

It’s possible that AI could be used to auto-generate a 3D mesh from an AI conceptual image, but this remains a challenge, given the nature of AI image generation. There are some tools out there which are making some progress, by analysing the image to extract depth and spatial information, but the resultant mesh tends to come out as one lump, or as a bunch of meshes, incoherent for use as a BIM model or for downstream use.

Back in 2022, we tried taking 2D photos and AI-generated renderings from Hassan Ragab into 3D using an application called Kaedim. But the results were pretty unusable, not least because at that time Kaedim had not been trained on architectural models and was more aimed at the games sector.

Of course, if you have multiple 2D images of a building, it is possible to recreate a model using photogrammetry and depth mapping.

AI in AEC – text to 3D

It’s possible that the idea of auto-generating models from 2D conceptual AI output will remain a dream. That said, there are now many applications coming online that aim to provide the AI generation of 3D models from text-based input.

The idea here is that you simply describe in words the 3D model you want to create – a chair, a vase, a car – and AI will do the rest. AI algorithms are currently being trained on vast datasets of 3D models, 2D images and material libraries.

While 3D geometry has mainly been expressed through meshes, there have been innovations in modelling geometry with the development of Neural Radiance Fields (NeRFs) and Gaussian splats, which represent colour and light at any point in space, enabling the creation of photorealistic 3D models with greater detail and accuracy.

Today, we are seeing a high number of firms bringing ‘text to 3D’ solutions to market. Adobe Substance 3D Modeler has a plug-in for Photoshop that can perform text-to-3D. Similarly, Autodesk demonstrated similar technology — Project Bernini — at Autodesk University 2024.

However, the AI-generated output of these tools seems to be fairly basic — usually symmetrical objects and more aimed towards creating content for games.

In fact, the bias towards games content generation can be seen in many offerings. These include Tripo, Kaedim, Google DreamFusion and Luma AI Genie.

There are also several open source alternatives. These include Hunyuan3D-1, Nvidia’s Magic 3D and Edify.

AI in AEC – the Schleusner viewpoint

When AEC Magazine spoke to Greg Schleusner of HOK on the subject of text-to-3D, he highlighted D5 Render, which is now an incredibly popular rendering tool in many AEC firms.

The application comes with an array of AI tools, to create materials, texture maps and atmosphere match from images. It supports AI scaling and has incorporated Meshy’s text-to-AI generator for creating content in-scene.

That means architects could add in simple content, such as chairs, desks, sofas and so on — via simple text input during the arch viz process. The items can be placed in-scene on surfaces with intelligent precision and are easily edited. It’s content on demand, as long as you can describe that content well in text form.

Schleusner said that, from his experimentation, text-to-image or image-tovideo tools are getting better, and will eventually be quite useful — but that can be scary for people working in architecture firms. As an example, he suggested that someone could show a rendering of a chair within a scene, generated via text to AI. But it’s not a real chair, and it can’t be purchased, which might be problematic when it comes to work that will be shown to clients. So, while there is certainly potential in these types of generative tools, mixing fantasy with reality in this way doesn’t come problem-free.

It may be possible to mix the various model generation technologies. As Schleusner put it: “What I’d really like to be able to do is to scan or build a photogrammetric interior using a 360-degree camera for a client and then selectively replace and augment the proposed new interior with new content, perhaps AI-created.”

Gaussian splat technology is getting good enough for this, he continued, while SLAM laser scan data is never dense enough. “However, I can’t put a Gaussian splat model inside Revit. In fact, none of the common design tools support that emerging reality capture technology, beyond scanning. In truth, they barely support meshes well.”

AI in AEC – LLMs and AI agents

At the time of writing, DeepSeek has suddenly appeared like a meteor, seemingly out of nowhere, intent on ruining the business models of ChatGPT, Gemini and other providers of paid-for AI tools.

Schleusner was early into DeepSeek and has experimented with its script and code-writing capabilities, which he described as very impressive.

LLMs, like ChatGPT, can generate Python scripts to perform tasks in minutes, such as creating sample data, training machine learning models, and writing code to interact with 3D data.

Schleusner is finding that AI-generated code can accomplish these tasks relatively quickly and simply, without needing to write all the code from scratch himself.

“While the initial AI-generated code may not be perfect,” he explained, “the ability to further refine and customise the code is still valuable. DeepSeek is able to generate code that performs well, even on large or complex tasks.”

WIth AI, much of the expectation of customers centres on the addition of these new capabilities to existing design products. For instance, in the case of Forma, Autodesk claims the product uses machine learning for real-time analysis of sunlight, daylight, wind and microclimate.

However, if you listen to AI-proactive firms such as Microsoft, executives talk a lot about ‘AI agents’ and ‘operators’, built to assist firms and perform intelligent tasks on their behalf.

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella is quoted as saying, “Humans and swarms of AI agents will be the next frontier.” Another of his big statements is that, “AI will replace all software and will end software as a service.” If true, this promises to turn the entire software industry on its head.

Today’s software as a service, or SaaS, systems are proprietary databases/silos with hard-coded business logic. In an AI agent world, these boundaries would no longer exist. Instead, firms will run a multitude of agents, all performing business tasks and gathering data from any company database, files, email or website. In effect, if it’s connected, an AI agent can access it.

At the moment, to access certain formatted data, you have to open a specific application and maybe have deep knowledge to perform a range of tasks. An AI agent might transcend these limitations to get the information it needs to make decisions, taking action and achieving business-specific goals.

AI agents could analyse vast amounts of data, such as a building designs, to predict structural integrity, immediately flag up if a BIM component causes a clash, and perhaps eventually generate architectural concepts. They might also be able to streamline project management by automating routine tasks and providing real-time insights for decision-making.

AI agents could analyse vast amounts of data, such as a building designs, to predict structural integrity, immediately flag up if a BIM component causes a clash, and perhaps eventually generate architectural concepts

The main problem is going to be data privacy, as AI agents require access to sensitive information in order to function effectively. Additionally, the transparency of AI decision-making processes remains a critical issue, particularly in high-stakes AEC projects where safety, compliance and accuracy are paramount.

On the subject of AI agents, Schleusner said he has a very positive view of the potential for their application in architecture, especially in the automation of repetitive tasks. During our chat, he demonstrated how a simple AI agent might automate the process of generating something as simple as an expense report, extracting relevant information, both handwritten and printed from receipts.

He has also experimented by creating an AI agent for performing clash detection on two datasets, which contained only XYZ positions of object vertices. Without creating a model, the agent was able to identify if the objects were clashing or not. The files were never opened. This process could be running constantly in the background, as teams submitted components to a BIM model. AI agents could be a game-changer when it comes to simplifying data manipulation and automating repetitive tasks.

Another area where Schleusner feels that AI agents could be impactful is in the creation of customisable workflows, allowing practitioners to define the specific functions and data interactions they need in their business, rather than being limited by pre-built software interfaces and limited configuration workflows.

Most of today’s design and analysis tools have built-in limitations. Schleusner believes that AI agents could offer a more programmatic way to interact with data and automate key processes. As he explained, “There’s a big opportunity to orchestrate specialised agents which could work together, for example, with one agent generating building layouts and another checking for clashes. In our proprietary world with restrictive APIs, AI agents can have direct access and bypass the limits on getting at our data sources.”

Conclusion

For the foreseeable future, AEC professionals can rest assured that AI, in its current state, is not going to totally replace any key roles — but it will make firms more productive.

The potential for AI to automate design, modelling and documentation is currently overstated, but as the technology matures, it will become a solid assistant. And yes, at some point years hence, AI with hard-coded knowledge will be able to automate some new aspects of design, but I think many of us will be retired before that happens. However, there are benefits to be had now and firms should be experimenting with AI tools.

We are so used to the concept of programmes and applications that it’s kind of hard to digest the notion of AI agents and their impact. Those familiar with scripting are probably also constrained by the notion that the script runs in a single environment.

By contrast, AI agents work like ghosts, moving around connected business systems to gather, analyse, report, collaborate, prioritise, problem-solve and act continuously. The base level is a co-pilot that may work alongside a human performing tasks, all the way up to fully autonomous operation, uncovering data insights from complex systems that humans would have difficulty in identifying.

If the data security issues can be dealt with, firms may well end up with many strategic business AI agents running and performing small and large tasks, taking a lot of the donkey work from extracting value from company data, be that an Excel spreadsheet or a BIM model.

AI agents will be key IP tools for companies and will need management and monitoring. The first hurdle to overcome is realising that the nature of software, applications and data is going to change radically and in the not-too-distant future.

Main image: Stable Diffusion architectural images courtesy of James Gray. Image (left) generated with ModelMakerXL, a custom trained LoRA by Ismail Seleit. Follow Gray on LinkedIn