In all mature markets, leading software applications eventually face competition from up-starts that benefit from fresh new approaches. Today’s established BIM authoring tools have looked fairly secure, with few daring to take them on. Arcol is preparing to give it a go

As software matures, and users gain expertise while file formats lock in legacy data, it gets very hard – even daunting – to consider switching to a competitive application. Practices must consider the cost of retraining, the possibility of being out of step in a collaborative world, and the loss of all that past investment. It’s not something to be taken lightly.

There are, of course, times when switching makes sense. You might feel the software you use lacks innovation with few additional productivity gains, or the costs go up and the past investment seems to have locked you into a dysfunctional relationship.

Historically speaking, the biggest driving force in customer migration comes when there are fundamental changes to the technology platforms on which software has been written. In the past this happened when business computing went from Unix to DOS and again in the change from DOS to Windows. If the software vendors are to be believed, the next platform is the cloud which could lead to another potential extinction level event for market leading software applications.

The BIM software market is an interesting segment to analyse. We have a market-dominating central player, Autodesk with Revit, together with Nemetschek’s Archicad, Allplan and Vectorworks, plus some geographic local winners such as Italy’s ACCA.

BIM first dominated the architectural design sphere and then slowly grew in structural and then Mechanical Electrical and Plumbing (MEP). The built environment market has always been slow to adopt, and the change from 2D drawings to 3D models still has some way to go.

If anything, many are using BIM as just another way to produce drawings, which are still the lingua franca and contractual basis for much of the industry.

Revit holds a very dominant position, with well over a million seats globally. While talking with frustrated architects who don’t understand why there aren’t more applications to choose from, the reality is that unless you are established and have an installed base, it’s very tough to enter what is essentially an oligopoly.

In discussions with venture capitalists and business angels who have considered developing a Revit competitor, they estimate the amount of money required being upwards of $20 million – some suggesting $100 million!

Part of this is because with market leading and established tools having had 20 years of development (OK, maybe 15!), a new tool from a start-up can only offer a fraction of the capability. Above the cost of development, the start-up would have to spend a fortune in marketing to convince existing customers to change horses. That is not a task to be taken lightly.

The reason there have been so few BIM start-ups is because the risk/reward is so high compared to venture capitalists funding yet another massing tool, or collaborative data environment application, which might get acquired by one of the big software firms.

Green shoots

Picking back up on the change of platform, venture capitalists now rarely invest in applications which are written for the desktop. If you have an idea for a software application that resides on a hard drive on a PC, you’re going to get little love from the money men.

They know the business model of the future is cloud and subscription and oddly, Autodesk is showing the way here. The thinking is, the first developer to properly produce a cloud-based BIM tool could well steal the lead on the incumbent desktop tools. Tie that in with well-publicised grievances of customers over lack of development and cost of ownership and there are a number of new players rising to the challenge.

New kid on the block

It’s unusual for us to write about a company with software not yet even in beta, but a new start-up called Arcol recently came to our attention, publicising a manifesto stating its development goals and aims, with respect to the grumblings permeating the industry.

The company is headed up by Paul O’Carroll, who comes from a games development background, and established Arcol to create a cloud-based building design and documentation tool which runs in a browser.

He recently moved to the United States and has managed to get $3.6 million in seed funding from some very interesting people, who know the AEC industry very well. One is Amar Hanspal (CEO of Brightmachines), formerly of Autodesk, where he ran all product development. The other is Procore’s CEO Tooey Courtemanche.

Hanspal knows Revit’s faults and has his own ideas as to what a modern BIM tool would look like, while Courtemanche is in a daily knife fight with Autodesk for the construction documentation and management layer with Procore vs Autodesk’s Construction Cloud.

Arcol also already has 7,000 firms signed up for a trial.

Arcol’s manifesto opens-up with a strong statement that is clearly fighting talk

Most design tools are from the late nineteen hundreds. We need to bring the magic back to design. We need something powerful, intuitive, and collaborative.

Think of how much technology has changed in the past two decades. Google docs. Slack. Zoom. The iPhone. While almost every product we touch has become web-based, collaborative, and consumer focused, for some reason, our design tools are still stuck in an ancient desktop paradigm of the 1990s.

We believe that 3D building design tools should be powerful, yet easy to use. Web-based, intuitive, and most importantly collaborative.

CAD went mainstream in the 80’s, and BIM came soon after, but since then it seems like tools have lost the magic. Over time they’ve gotten clunky, slow, unintuitive, and driven by greed — incumbents are public companies and therefore they’re [sic] only growth metric is profit.

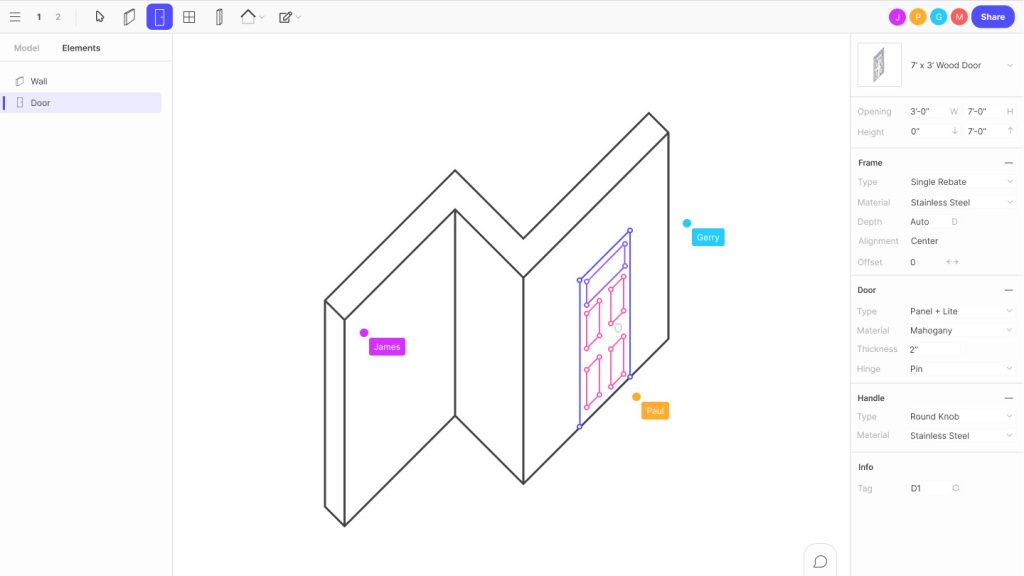

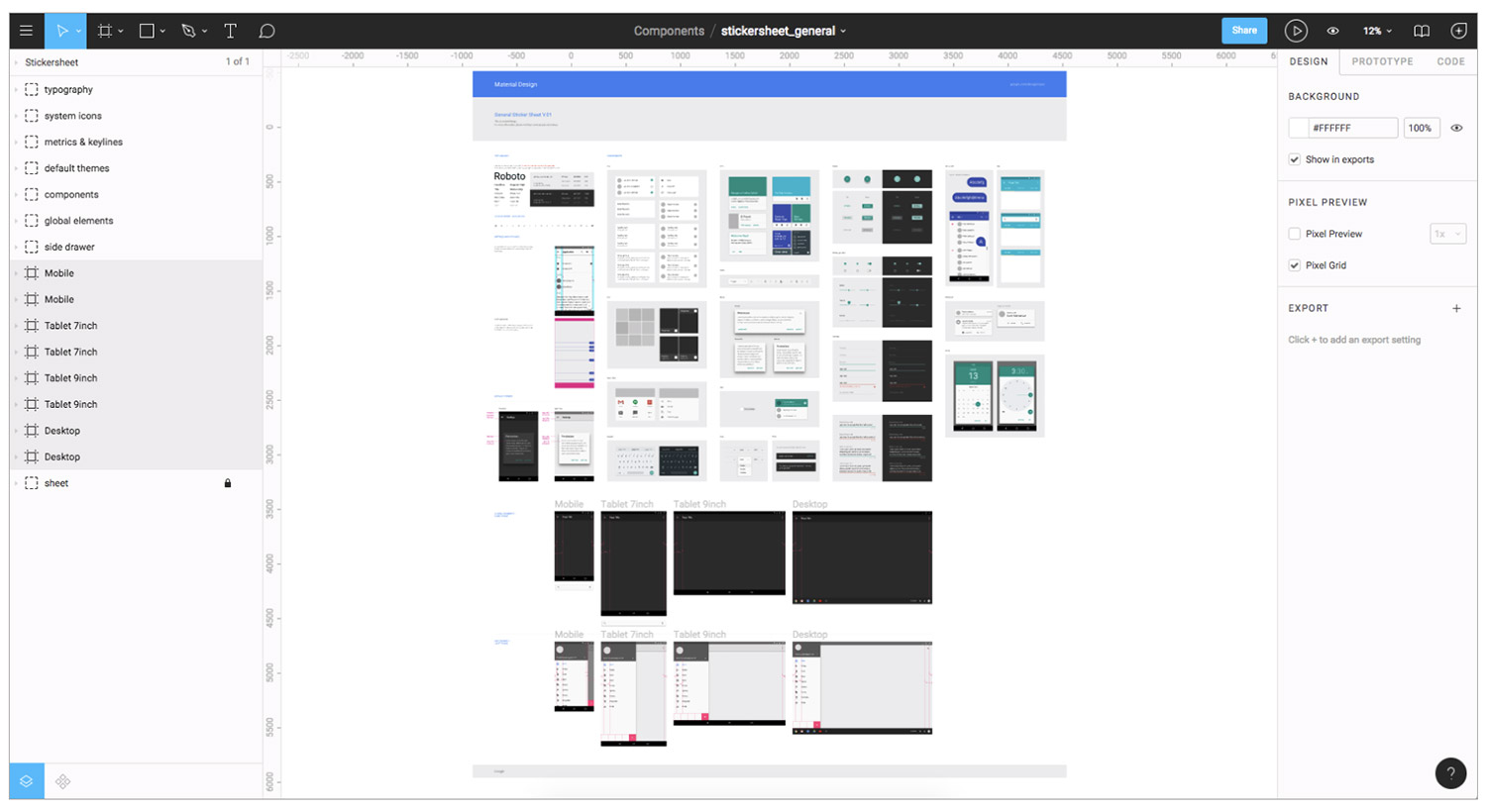

O’Carroll then explains that he has been inspired to develop a BIM application from seeing new generations of tools like ‘figma’, a graphical application for collaborative diagramming. With this application, multiple users can work simultaneously on virtual whiteboards, designing interfaces, templates, or map out UI/UX design. By having a look at the figma website you’d get a clear idea at how this could potentially work in a collaborative BIM design environment. It would be a centralised system on which all designers simultaneously worked.

By starting afresh, O’Carroll believes that he can change the paradigm by rethinking the way design authoring applications should work. The first fundamental is web-based, browser-accessible, enabling centralised collaborative workflows, with no install.

Addressing collaboration, O’Carroll identifies Slack as a great example, “Slack allows you to have that information indexable, searchable, trackable and allows you to organise asynchronous communications independent of a singular closed silo. In a similar way we are building a tool to contain the entire history of a project — markups, comments, sketches… all the work that happens on the periphery while designing a building.”

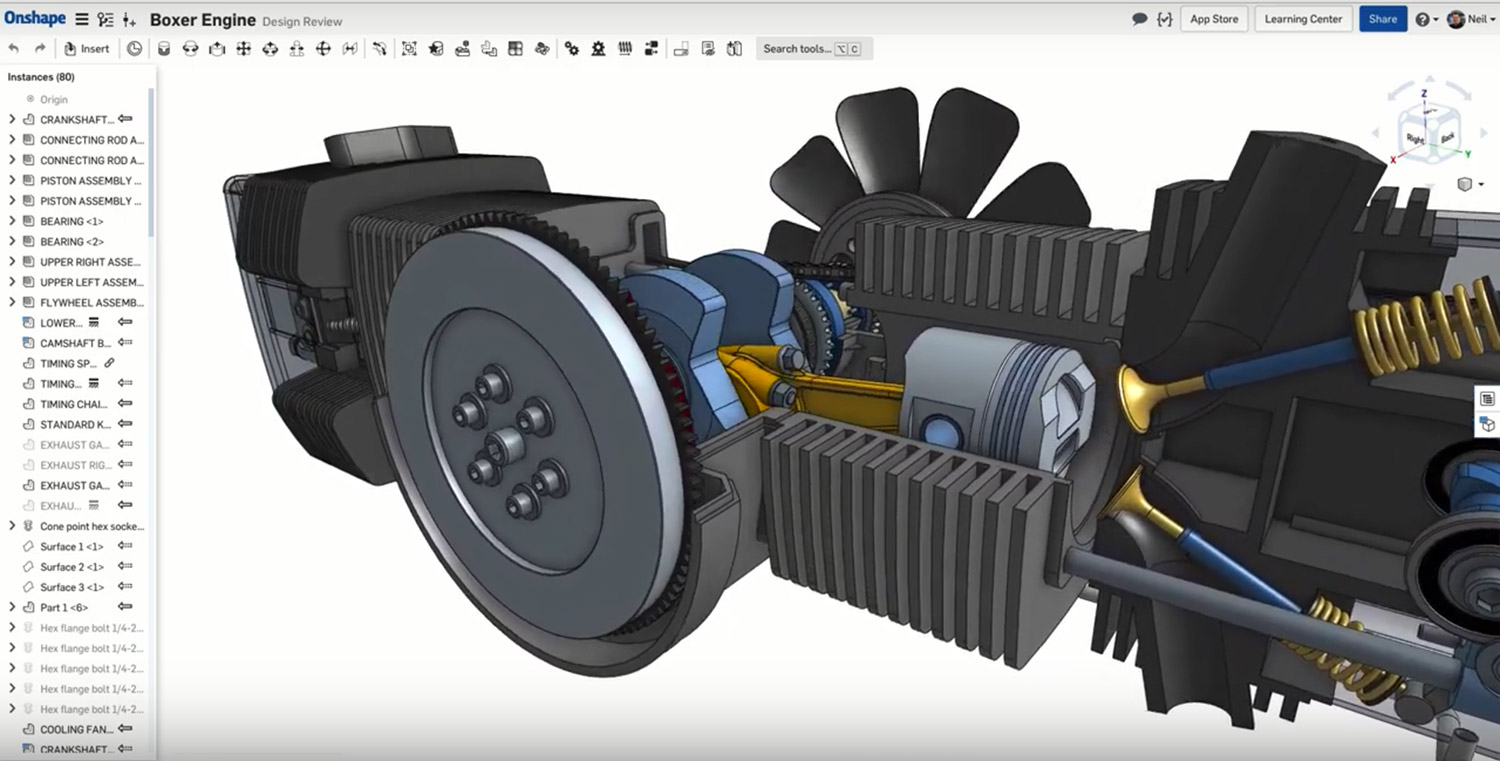

Obviously Arcol will deliver 2D and 3D capabilities and, for this, O’Carroll takes inspiration from PTC Onshape, a mechanical CAD modelling tool, which competes against the mainly desktop-based world of Dassault Systèmes Solidworks, Autodesk Inventor, and Siemens Solid Edge etc.

Autodesk is also challenging with its cloud-based Fusion, but despite millions of dollars spent, the cloud-based apps have yet to make a dent in that industry’s 800lb gorilla – Solidworks, which is based on Windows and decimated the UNIX modelling tools in the 1990s. One could argue that if cloud was the next platform, then why hasn’t it taken off in the manufacturing space, where there are already two mature cloud-based systems?

The added complication is that, essentially, we’re talking about a replacement market, as opposed to virgin territory. As a start-up, your potential new customers have already invested in something, increasing their cost of moving.

Innovation

The one danger is producing a new product that just replicates the old. Being on the cloud does not make for a better product. O’Carroll identifies several areas where he’s looking for Arcol to differentiate itself from the competition.

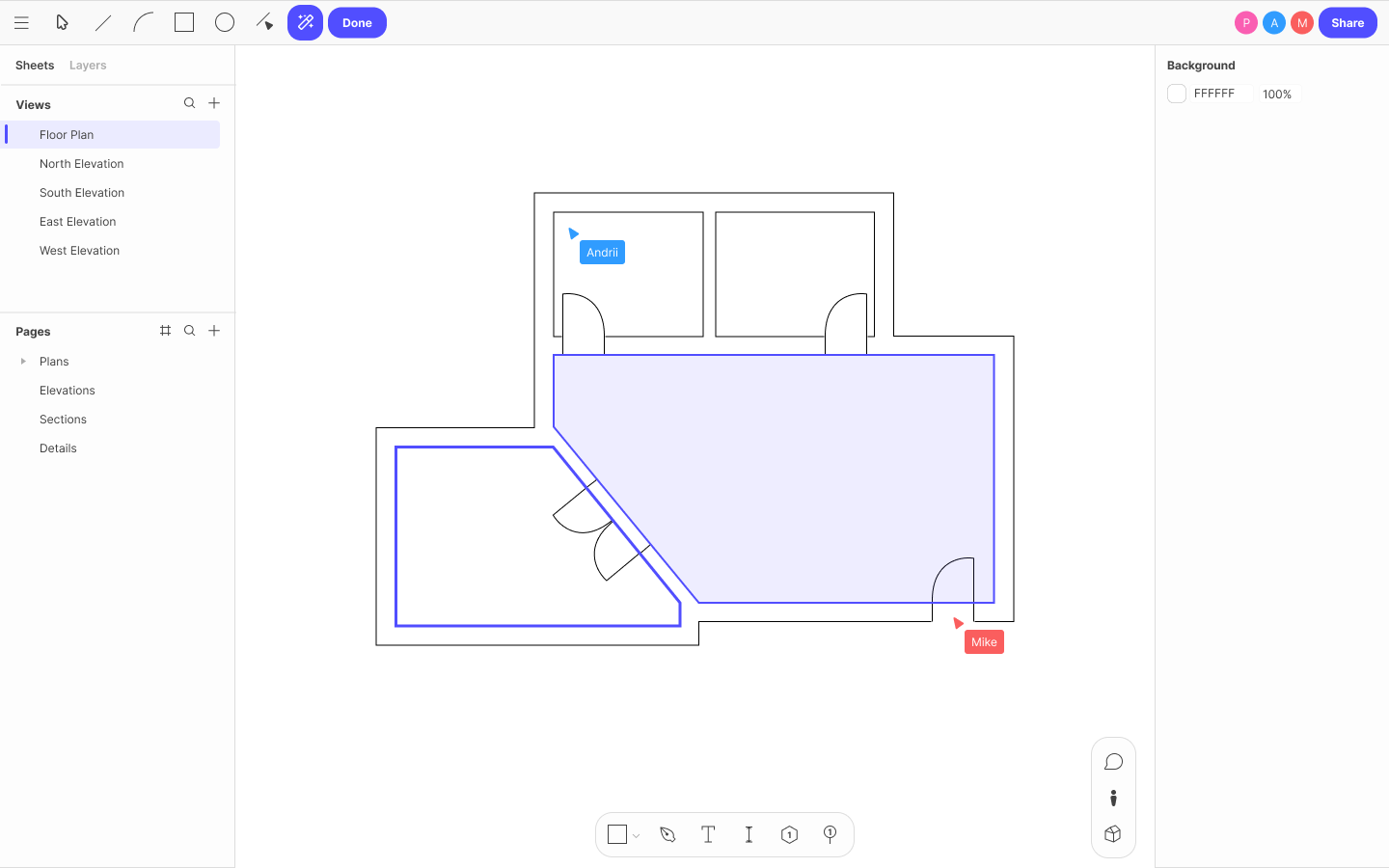

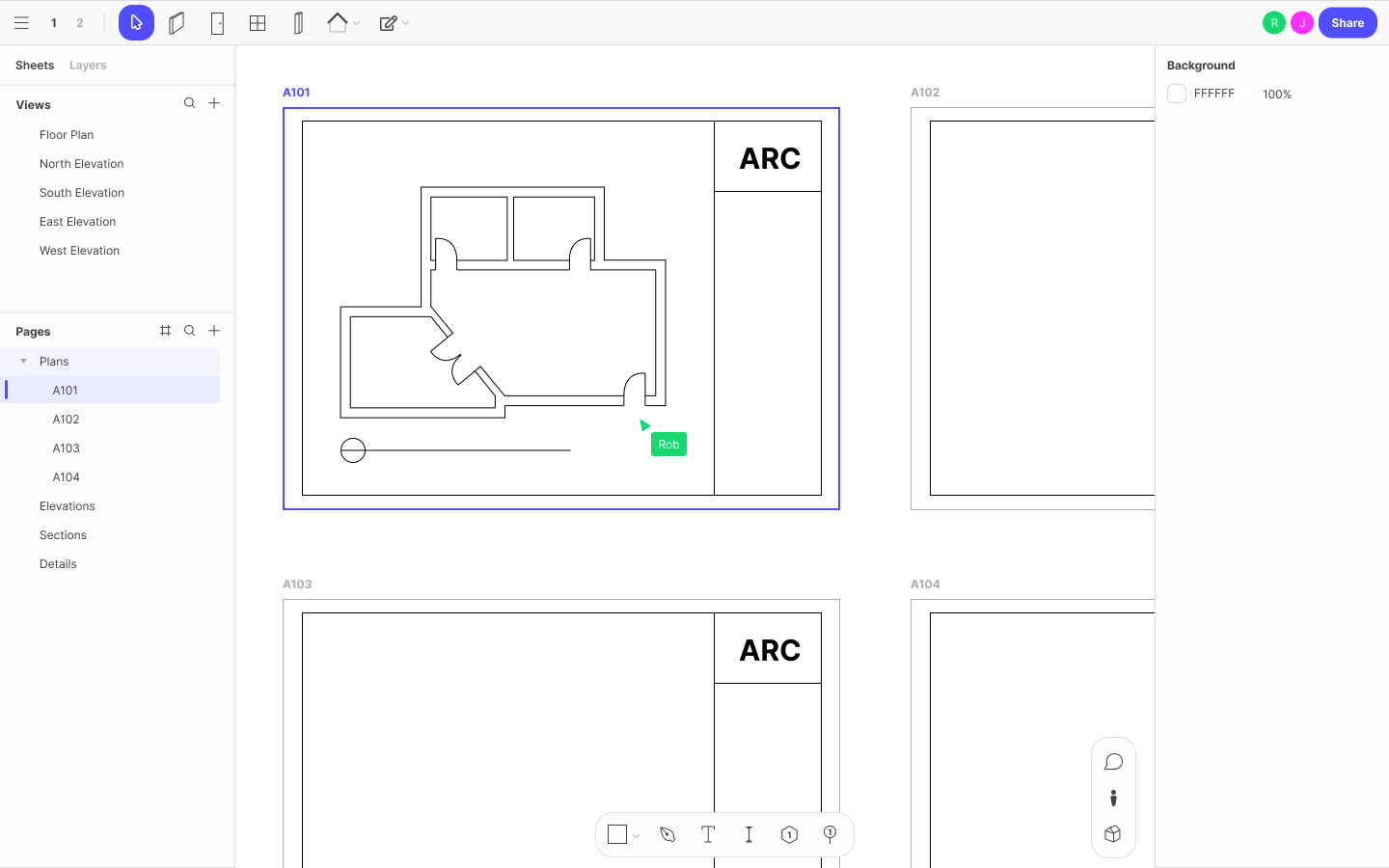

One of the fundamental differences will be an infinite workplane, so users don’t need to flip-flop between interfaces and modes to create drawing sections and elevations.

“Sketching, drawing and editing should be as intuitive as possible. This is the lowest level form of interaction we have in CAD — yet these tools really haven’t been innovated upon much in the last 20 years.”, explains O’Carroll. “We believe that it shouldn’t take you an hour and a half to create a window component with a curved top. We had a thought: rather than having to edit a family in another window in some other editor, what if you could simply make changes to a sketch of the window to add the curve? In Arcol you can do just that.

“Every 3D component is built from an underlying 2D sketch. You can easily access the base sketch, make changes directly in the model, and then save your changes to have them cascade to the 3D representation.”

I can’t fault either O’Carroll’s enthusiasm or existing software inspirations. Even though we’ve seen no software product there’s plenty to chew on and project.

The problem with new modelling software for architecture, is they come out so limited in functionality early on, that they are always compared to SketchUp, or described as being ideal for conceptual modelling.

Mature incumbents benefit from having decades of feedback from professional users, enabling their software to handle many real-world edge cases – these are all the nuances that get added into commands to handle niche conditions to give flexibility. e.g. all the improvements to staircases, MEP routing, 2D representation, structural detailing, requests based on different standards etc.

Getting the fundamentals right is key, but getting the level of functional detail and sheer breadth of features is climbing the north face of the Eiger for any challenger.

In total, Arcol has $5 million to flesh this out, and now has two backers with plenty of industry experience and, to a certain extent, axes to grind.

Arcol will be in beta testing in 2022, with the first public release scheduled for later this year.