Chun Qing Li is one of the UK’s true innovators. As an architect, he is intent on rebuilding the link between design, fabrication and commercial reality, and that has meant writing his own fabrication-ready design system, writes Martyn Day

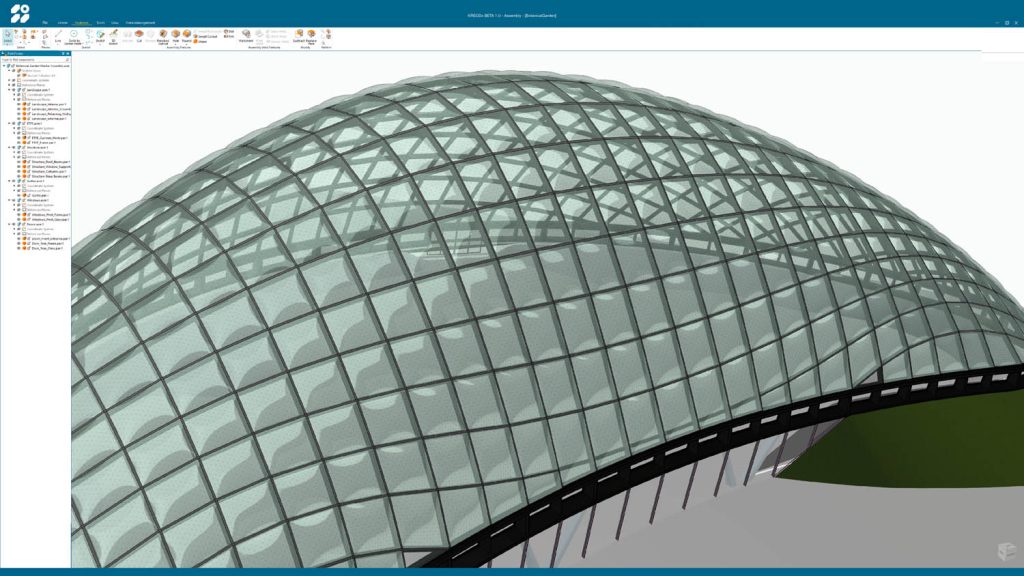

Early-phase engineering and architectural design is the least visible and least well rewarded part of a building project, yet it is often the phase that most strongly determines whether a scheme ever becomes affordable or buildable. In an industry that still absorbs extraordinary financial risk during concept and feasibility, decisions made before a single drawing is signed off routinely lock in cost, procurement behaviour and even long-term operational performance. It is into this uncomfortable gap between design intent and commercial reality that Chun Qing Li has stepped in with KREODx, a design system that is neither conventional BIM nor a parametric plug-in, but a fabrication-aware solid modeller built from scratch.

Li’s journey to this point is unconventional, even by AEC startup standards. Trained as an architect, he went on to run his own construction company, then decided that the only way to resolve the structural contradictions he kept encountering between drawings, procurement and site reality was to use a manufacturing-grade mechanical CAD system. He began by using Dassault Systèmes Catia, which is used extensively in the automotive and aerospace sectors. He customised the system to be more building-component aware and started to wonder whether the layer he was creating might become a commercial product that other architects could use. “I was using Catia. It can model anything,” he recalls. “But out of the box it doesn’t understand buildings, tolerances, procurement, or how things are actually fabricated.”

The implication he drew from that experience was radical and slightly mad in equal measure. “I realised, if I want the computer to understand construction logic, I have to build the geometry engine myself.” It is a decision not for the light-hearted, and one that immediately separates KREODx from the long line of tools that attempt to civilise BIM from the outside.

Discover what’s new in technology for architecture, engineering and construction — read the latest edition of AEC Magazine

👉 Subscribe FREE here

This is the origin story of KREODx, a proprietary Parasolid-based solid modelling and automation platform, designed to treat buildings not as geometric compositions but as negotiated assemblies of manufacturable parts, constrained by tolerance, cost and supply chain reality from the outset.

What distinguishes KREODx from yet another attempt to refine BIM is that Li does not see design as the main problem domain at all. He sees it as merely the first compression point in a much longer chain of economic consequence. In his framing, most of the financial damage in construction is not caused by bad drawing, but by bad information continuity, where assumptions made during concept quietly metastasise into procurement decisions, site improvisation, maintenance burden and asset write-downs years later. “Design decisions shouldn’t just be about what looks right,” he argues. “They should be about what can actually be built, paid for, complied with and operated.”

This is why KREODx is conceived not as a frontend modeller, but as a lifecycle system that carries validated geometry, system logic, compliance data and cost truth from design through manufacture, construction, occupation and long-term operation. The ambition is not better drawings, but fewer financial surprises across the entire asset lifecycle.

The architect as general

Li’s technical eccentricity is rooted in a deeper professional and political critique of the AEC industry. He argues that most construction software is built by people who have never been financially or legally exposed to site failure, and that this explains why the industry keeps generating tools that accelerate drawing production without addressing risk, miscommunication or cost certainty.

“Would you hire a solicitor to perform heart surgery?” he asks. “If it’s no, why would you hire a software engineer to solve the AEC industry problems? He or she doesn’t even know the size of the brick.”

For Li, this disconnect is not just a tooling problem, it is a governance failure. He sees architecture as having abdicated its historical role as system integrator, retreating into representational geometry while contractors, quantity surveyors and manufacturers quietly absorb the commercial consequences of design ambiguity.

“If you draw something that cannot be built, or that will bankrupt the client, you’re not an architect,” he says. “You’re just an artist with liability.”

This is what he means by the architect as general. Not a nostalgic power grab, but a demand that the lead designer once again takes responsibility for the full technical and economic coherence of a building, including how parts are fabricated, how they are procured and how cost behaves under design change. In Li’s world view, design authority is not earned through aesthetic vision but through predictive accuracy. In a riskaverse industry, Li is running towards the gunfire, not from it.

That philosophy is why KREODx is not built on top of Revit, Rhino or Grasshopper. Those platforms, in his view, are optimised for geometric flexibility and visual coordination, not for manufacturing truth. They allow almost anything to be drawn and then rely on downstream consultants and contractors to reconcile fantasy with feasibility.

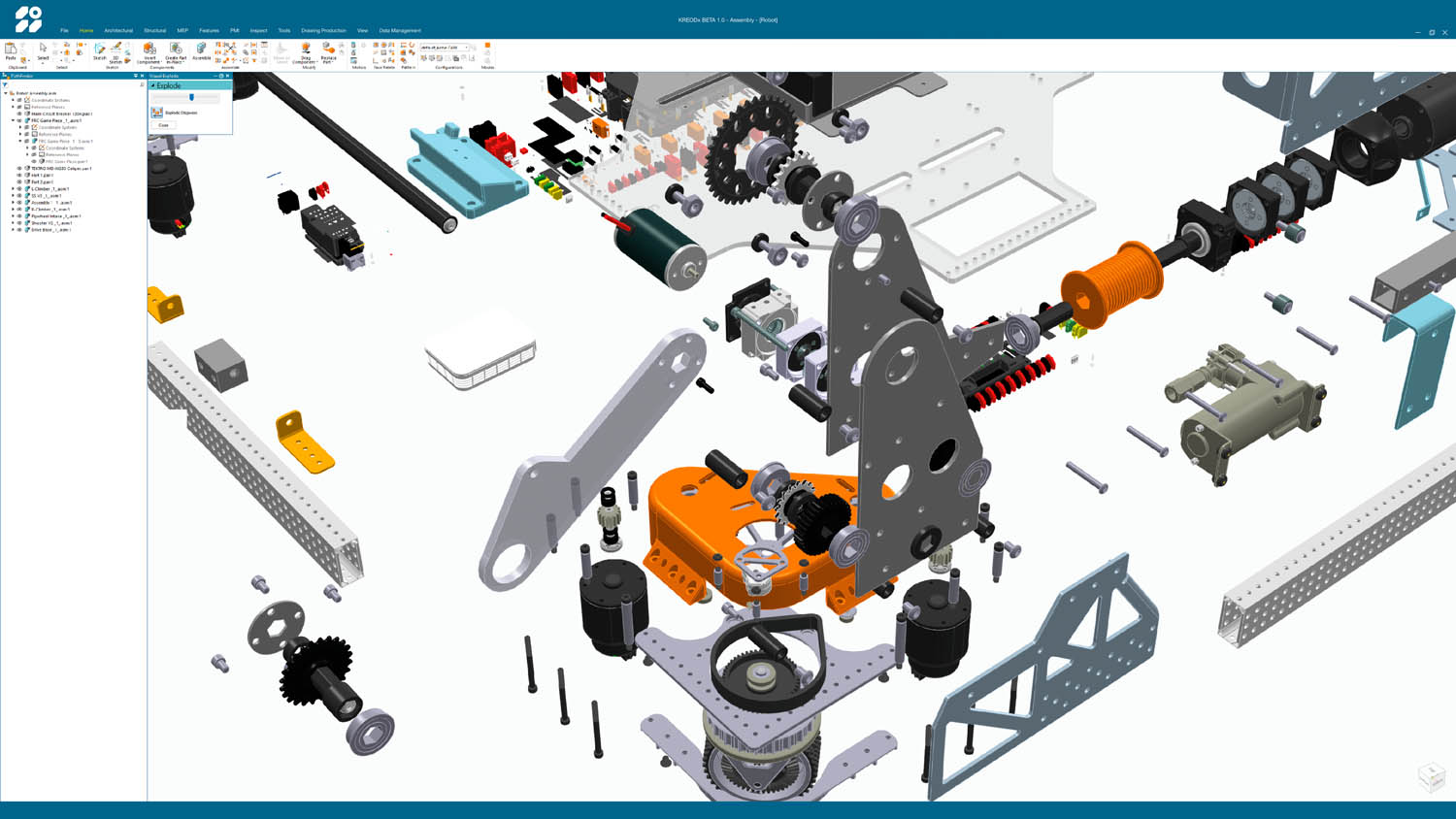

KREODx, in contrast, is built as a parametric solid modeller. Its primary job is not to draw buildings but to instantiate real building systems. Geometry is subordinate to constraint. Every component carries embedded rules about maximum size, allowable spans, connection logic, tolerances and cost consequences. If a designer exceeds a manufacturing limit or creates a bespoke variant that breaks standard production economics, the system flags the consequence immediately.

If you draw something that cannot be built, or that will bankrupt the client, you’re not an architect. You’re just an artist with liability

What Li is really building here looks less like architectural software and more like a form of building-scale systems engineering. The intellectual lineage is closer to aerospace or automotive product lifecycle management (PLM) than to BIM authoring. KREODx behaves as an expert system, embedding manufacturing constraints, assembly logic and interface rules directly into the geometry layer so that design choices become executable technical decisions rather than optimistic suggestions.

Li describes it bluntly as an AEC fintech play. “This is not a software startup. The product is financial certainty,” he says. In other words, geometry is just the user interface for a deeper economic machine that exists to make cost, compliance and constructability behave deterministically instead of probabilistically.

This kernel-level control is what allows KREODx to behave more like an expert system than a drafting tool. It is also what makes Li’s decision to abandon Catia comprehensible. Aerospace software can model almost anything, but it does not contain the glue logic of construction, the rules that determine whether a panel can be transported, whether a joint can be assembled on site or whether a dimension drift will cascade into rework.

Li’s ambition is to capture that logic once and reuse it everywhere, instead of forcing every project team to rediscover it through failure.

Internally, Li structures this worldview around what he calls DEMACOMB, shorthand for Design, Engineering, Manufacturing, Assembly, Construction, Occupation, Maintenance and Beyond. The acronym is less important than the provocation behind it. Buildings, in his view, are not projects with an endpoint at practical completion, but long-lived technical systems whose real costs and risks emerge years after the ribbon is cut. Most digital tools stop caring the moment the keys are handed over. KREODx is explicitly designed to retain system logic, product provenance and spatial intelligence across those later phases, so that a decision made in concept does not become an untraceable liability during maintenance or retrofit.

That long view is unusual in an industry that still treats handover as a finish line rather than a liability transfer.

Credibility under pressure

The intellectual coherence of this argument would be unconvincing if it had not been forged under real financial pressure. Li’s authority in this domain comes from having tested his ideas on his own live projects, most notably during the refurbishment of Browns Hotel in London.

The project carried huge penalties for delays. During the fit-out, Li discovered that the interior designer, the principal contractor and the on-site carpenter were not in sync. “I spoke to the interior designer. I spoke to the principal contractor. I spoke to the carpenter. Three different dimensions,” he says. “One was fifty nine millimetres out.”

On bespoke panels and joinery, that discrepancy would have triggered catastrophic rework. “Every day we were late, it was ten thousand pounds,” Li recalls.

Instead of issuing another drawing revision, he 3D scanned the rooms, modelled every component in his own software and sat down with the carpenters to negotiate tolerances digitally before anything was cut. Once the dimensions were agreed, the data was sent directly for CNC fabrication. The parts fitted perfectly.

“The carpenter said, ‘We should have had you much earlier!’,” Li said.

This episode functions as KREODx’s credibility crucible. It demonstrates what happens when errors are found in software rather than on site, and why Li believes fabrication-level modelling is not an indulgence but an economic necessity.

Browns Hotel was not a one-off. KREODx has been quietly exercised across a string of live projects, from the remastering of the London Olympic Pavilion, originally delivered in 2012, to residential schemes across London, Surrey and Kent, modular housing projects, golf driving ranges and other Modern Methods of Construction deployments. These are not laboratory pilots. They are commercial projects executed under real contractual risk, using KREODx as both a design environment and a fabrication coordination layer.

That matters, because it reframes the software not as a speculative product vision, but as a delivery system that has already survived contact with site reality multiple times.

Rebuilding the geometry stack

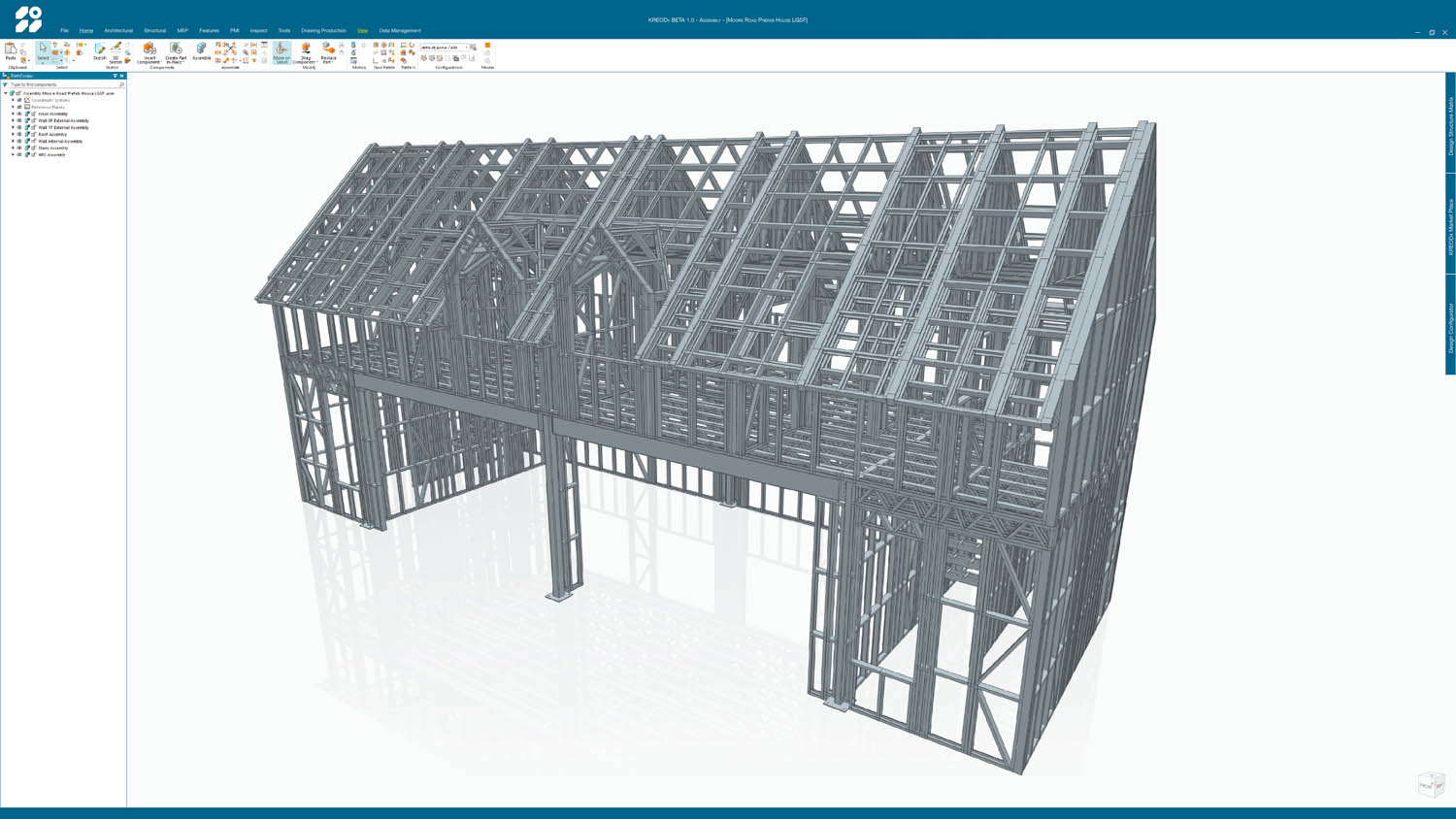

KREODx emerged from similar repeated experiences as a full-stack attempt to rebuild the geometry layer of construction around manufacturing truth rather than low-tolerance representation. It is a parametric solid modeller whose primitives are not walls and slabs but real components sourced from real manufacturers.

Li describes the system as a form of digital DfMA, borrowing from aerospace and automotive practice. Designers work with intelligent component libraries rather than generic BIM families. Those libraries embed fabrication constraints, tolerance behaviour, cost curves and assembly logic. When components are combined, the system checks whether the resulting configuration is manufacturable, transportable and economically coherent. “If it goes beyond that you get an alert,” Li explains. “So this is going to be a unique product.”

This is not optimisation in the academic sense. It promises bounded reality. It ensures that what is being designed exists within the feasible envelope of the supply chain. The strategic implication is that early design stops being speculative. Instead of issuing abstract geometry and discovering its cost later, KREODx allows cost and constructability to co-evolve with the design of the form.

Uniblock

The practicality of this approach becomes clearer in the first commercial deployments of KREODx, particularly with manufacturers who live at the wrong end of architectural ambiguity. One such client is Uniblock, a UK supplier of an insulated, interlocking concrete formwork system.

Uniblock’s bottleneck was not manufacturing capacity but quotation throughput. The company received hundreds of 2D PDF drawings each month. To produce a quote, a team of five people manually rebuilt each scheme in Solidworks, generating a bill of quantities one house at a time. This allowed them to process roughly one project per day.

Li’s response was not to push KREODx directly into architectural practices. Instead, he built a narrow browser-based AI tool called Build X AI, designed to attack this specific pain point. “The output of every BIM system is the same. A 2D PDF,” Li says. “That’s where everything goes wrong, because there is no data left.”

Build X AI reads the uploaded drawings, generates a 3D model using Uniblock’s components and produces a bill of quantities and quotation in under a minute. “If my AI can read the drawings, build the model and generate the quantities, all the manufacturer has to do is press send,” Li explains.

For Uniblock, the economics are brutal and obvious. Replacing even two staff members covers the annual cost of the tool. The turnaround time collapses from days to minutes. Every enquiry can now be answered. “This is not the end product,” Li says. “It is a strategic beachhead.”

Reconnecting designers & fabricators

What makes the Uniblock deployment strategically interesting is not the AI trick itself but what it unlocks next. Once a manufacturer’s product logic exists in parametric form, it can be reused upstream in KREODx.

This is where Li’s longer-term ambition becomes visible. He is attempting to build a shared digital layer where designers work directly with fabrication-ready components sourced from manufacturers, and where those components carry live cost and procurement logic.

The commercial mechanics of this are deliberately opaque and business-sensitive at the moment, but the conceptual move is clear. Instead of design intent being handed off to contractors to reinterpret and value engineer, procurement becomes a direct extension of design.

“I specify the super window and the contractor comes back and says we’re not going to use Kingspan because it’s too expensive,” Li says. “But when you give it to a contractor, they use something else. Obviously, they downgrade it.”

KREODx is designed to prevent that substitution logic by collapsing specification and procurement into a single transaction layer. The architect specifies a real component. The client sees its real cost. The supply chain delivers exactly that component.

Li describes this as building the Amazon of the AEC industry. Not a retail interface, but a digital marketplace that links design, manufacturing and payment into a single source of truth.

The deeper implication is that adversarial supply chains become unnecessary. If cost is known early and locked in, contractors stop needing to protect margins through substitution. Clients stop being lied to about where money goes. Risk becomes visible and therefore negotiable.

Conclusion

KREODx is not interesting because it is clever software. It is interesting because it is an attempt to realign responsibility, authority and financial truth inside a deeply dysfunctional industry. What makes this especially persuasive, at least to me, is not the software itself but the way Li keeps forcing every abstract idea back into site-level consequence.

Li’s decision to abandon Catia and build his own Parasolid-based solid modeller is objectively irrational if judged by conventional startup metrics. It only becomes rational when seen as a response to a structural market failure, the inability of existing tools to connect design intent with fabrication reality and commercial consequence.

His vision of the architect as general is not about professional dominance. It is about professional accountability. It demands that the lead designer once again becomes responsible for whether a building can be fabricated, afforded and delivered without deception.

It is also, implicitly, about re-pricing risk in an industry that has never learned how to model it properly. From an investor or developer’s perspective, KREODx is less interesting as software than as infrastructure, a way of turning design decisions into auditable financial commitments rather than educated guesses. Once systems are configured, quantities resolved and assemblies validated, procurement stops being a negotiation and becomes a data outcome. Estimation gives way to quotation. Fragmentation gives way to traceability.

“You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete,” Li says, quoting Buckminster Fuller.

KREODx is not yet that model. It is still mainly an in-house, eccentric and unproven at scale. But it is one of the few attempts in the AEC technology landscape that actually targets the real problem, not drafting speed or visual coordination, but the financial lies embedded in the way buildings are currently designed and procured. The Uniblock case demonstrates that this world view can generate immediate commercial value without waiting for industry-wide adoption. It also reveals the deeper logic behind KREODx, where narrow automation tools generate parametric product data, which feeds intelligent libraries, which enable fabrication-aware design, which creates financial certainty, which attracts more manufacturers.

If Li succeeds, the consequence will not be prettier BIM. It will be fewer surprises on the journey between concept and fabrication, and a profession that reclaimed responsibility for the economic reality of the things it draws.