Paul Tallon, design and visualisation Manager at the 3M Buckley Innovation Centre (3M BIC) in Huddersfield, talks us through the process of building a virtual, to-scale version of the University of Huddersfield’s campus using ever-evolving 3D technology and drone data

Technology is advancing at an incredible rate and as a designer it’s crucial to stay ahead of the game and embrace new advancements to enhance our work. A couple of years ago my team started a project with the University of Huddersfield, well known for its striking buildings, to create a ‘virtual campus’ that could be viewed on screen or on a VR headset anywhere in the world. A campus that was realistic and allowed prospective students to explore and get information about their courses, facilities and even advice from staff.

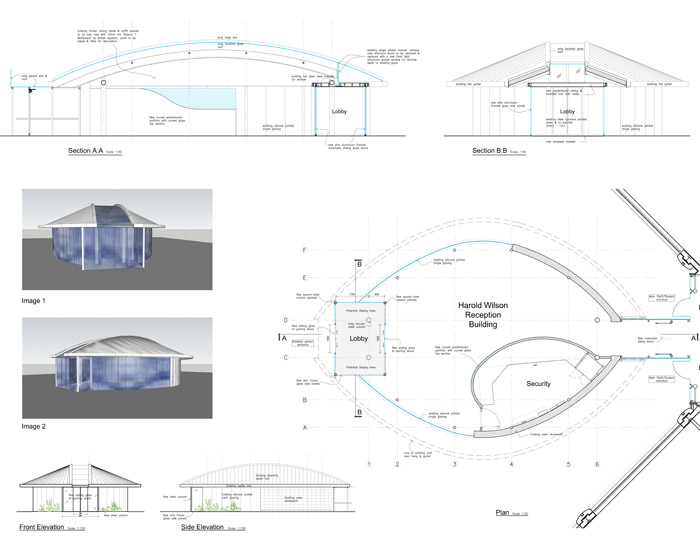

We were fortunate to get hold of the original architect’s 2D plans of each campus building from the local authority and the University’s Estates department. Usually this information is available from planning applications, however the campus has evolved so much over the years and meant that the format, scale and completeness was often varied and on occasion, inaccurate. Using electronic data and paper plans, supplemented with photographic reconnaissance, we could capture precise details, colours and comparisons between neighbouring buildings. Each building has its own character, ranging from Victorian gothic stone to contemporary glass and concrete.

Converting the records into CAD format enabled us to correct any errors, get consistent scales and build a portfolio covering every building on campus. These were modelled in 3ds max and then scaled using a current map of the town to ensure the correct gauge. We also captured other Huddersfield buildings, such as its iconic train station and Victorian bank buildings.

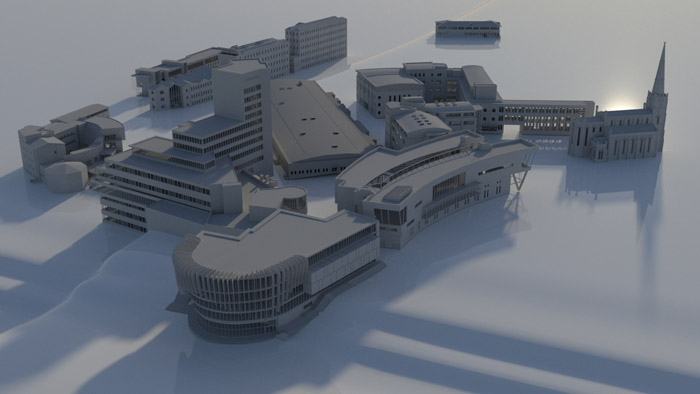

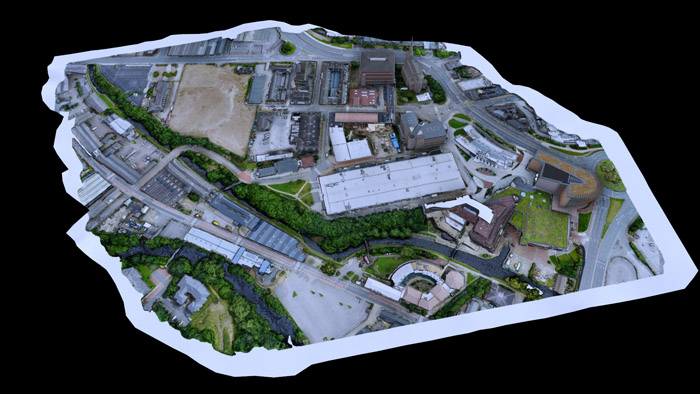

Working with a qualified and licensed drone pilot and with the permission of the University, using pre-submitted flight plans, we carried out a comprehensive aerial scan early on a Sunday when the campus was deserted. Using photogrammetry to process the photos, this provided us with a 3D mesh of the area and an accurate ‘footprint’ of every building. The buildings we had modelled accurately from plans could then be matched to the drone scan data so they could be positioned precisely to the exact scale and relative to their neighbours. Initial versions of each building were modelled with all the structural details but left white or grey.

Each building was rendered with colours, materials and textures to provide an accurate, photorealistic structure in the virtual campus. Pavements, grass and trees were also added to give virtual depth and realism.

Although this method was effective, it produced a very dense mesh containing many thousands of polygons – around 4 gigabytes of data and over 12 million triangulated points. It was too bulky to handle efficiently so we restructured the area in a more GPU/CPU friendly polygonal form.

It took us roughly two to three days of modelling per building, but once this was achieved we converted them to an FBX file format, built out a fully rendered version of the campus and then put into a game engine – Unreal Engine. You can walk around the buildings and also use an Oculus or any VR headset to navigate around campus. This benefits Building Information Modelling (BIM) as we can add in functionality as and when we need it; for example, for disabled users we can change the viewing height and the gait of the character to see how they can interact with the buildings.

We recently started using the Lumion 9 software, a new addition to our arsenal that offers a much faster pipeline. It has has allowed us to improve on our previous work and add even greater levels of photorealism to the visuals. Using this software, new buildings can be added, even at the concept stage and we can assess the potential impact on the built environment or neighbours as part of the planning process.

3D printed models of buildings have also been created of each of the buildings. Sometimes a physical 3D model makes it easier for the client to understand the dimensions of their building in relation to existing buildings. We also find it helps when designing process models and printing in 3D; the client can get to grips and quickly re arrange the “ elements” to have a new design.

We used the 3D Systems ProJet 2500 to print in SLA as this gives the most accurate detail (roughly 13 microns per layer). 3D printing the buildings needed to be reconsidered for their wall thicknesses and facade orientations ensuring that they faced in the right direction and that their walls were the correct thickness for printing to avoid warping. This was particularly important to help us understand the scales between buildings when printed out.

The possibilities with these advancing technologies are endless and can be adapted to enhance town planning projects or BIM and can also be used on variety of platforms. We are working with companies such as Value Chain based at the 3M BIC, that can map data sets, such as footfall onto the physical model of the campus and accurately pinpoint where students move across campus. This is something we are looking at developing in the next phase of the project using an avatar of the University’s Vice Chancellor, Professor Bob Cryan. Using a scan of his head and shoulders by means of the 3M BIC’s Artec Eva Spider handheld scanner we can implement this avatar to give users a virtual tour across campus in different languages.

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to our email newsletter or print / PDF magazine for FREE