Everybody’s talking about Design for Manufacturing and Assembly. While very few firms are actually doing it, the concept is attracting advanced BIM users, fabricators and software firms to try it out. Martyn Day looks at Autodesk’s efforts and future vision

When it comes down to digitisation, it might seem that manufacturing has nearly always been ahead of building and construction. However, this is not strictly true. In the late 70s and 80s, while high-end manufacturing was starting to rapidly adopt 3D modelling, high-end architecture firms were also using mini-computer-based 3D modelling programs such as RUCAPS, Sonata and GDS. The future looked to be 3D for all design systems.

With the advent of PC-based desktop 2D CAD in the late 80s, for some reason development of 3D modelling software for manufacturing exploded with small to-medium-size engineering firms quickly adopting Pro/Engineer, Unigraphics and SDRC I-DEAS and then Solidworks. Unfortunately, the AEC industry opted for the dark ages, mainly regressing to desktop 2D CAD or making low detail 3D models to make 2D drawings.

Meanwhile manufacturing went on to drive the development of G-code, computer numerical control (CNC), 3D printing and robotic assembly and manufacture, as well as driving quality, tolerance controls and supply chain management.

In the manufacturing space, 3D modelling of products and assemblies naturally fed into the digitisation of production, where volume of production is key. 3D models didn’t kill 2D drawing as a valid communication format but the 1:1 scale product definition model typically drives the process.

We have become used to being surrounded by beautifully engineered products. From cars and aeroplanes to Apple devices, we have become a society that is aware of engineering design and assembly. Anyone who is into cars will know how Nissan, Volkswagen, Audi, Renault, Peugeot and many others share common platforms for their cars, saving development time and money but allowing competition on their differentials which they add on top.

BIM barriers

BIM was not evenly spread in its adoption and took a long time to infiltrate traditional 2D practices. We had Graphisoft ArchiCAD, then three attempts from Autodesk – AutoCAD AEC (a UK variant), Architectural Desktop (ADT) (acquired from Softdesk) and then Autodesk bought the developer of Revit, Autodesk’s first AEC design code-base free from AutoCAD.

Meanwhile, Bentley Systems had MicroStation-based TriForma and there was SketchUp, pre-Google/Trimble, to popularise 3D. All these systems were primarily designed to model buildings and output drawings, the lingua franca of the AEC industry – because construction, by and large, was (and still is) a manual process and the contractual system firms operate in is based on drawings as a key deliverable.

By moving to a BIM / model-centric approach to design, unfortunately the AEC industry cannot easily segue into a digital fabrication future as easily as manufacturing has. Firstly, BIM models are not detailed enough for manufacturing and all BIM systems available today were developed for drawing production. Then there’s the process itself; Boeing owns the plane design and assembly and will use sub-contractors to create parts. It’s top down, while AEC projects have structures that are typically flatter, more nebulous, are siloed and go through many more phases.

I’ve come to feel that today’s BIM systems are already feeding space-age data into a stone age process

A digital fabrication change in AEC will also require substantial changes in workflow, process and the upskilling of production knowledge. On the face of it, this will be a considerable challenge for the industry to digest, as it will impact everything from the tools to the very fabric of the building.

I’ve come to feel that today’s BIM systems are already feeding space-age data into a stone age process, but the underwhelming expectation of the contracted output (2D), often questions the effort required to produce the input. Many of those that have taken the trouble to get to Level 2 BIM are undoubtedly producing COBie files that will sit on a USB stick gathering dust in a drawer. However, my pet issue, is how today’s BIM tools will impede the industry in its efforts to digitise building manufacturing. It’s like putting a fish on a bicycle.

Process

The AEC industry is perfectly aware that it is re-designing the wheel time and time again. With every building being a prototype and a one off, it’s hard to see the benefit of pre-manufacture. And while many firms will point out that modular can lead to non-descript rectangular buildings, star practices like Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA) have embraced prefabrication and modularisation for their clients.

The global firm’s sustainable timber designs for Roatán Próspera, a modular housing project for an island near Honduras, are assembled off-site in a ‘kit of parts’, enabling up to 15,000 variations. As a practice, ZHA is perfectly capable of modelling buildings and building components and creating the G-code to drive the machines at its remote fabricator.

To embrace modular design, and get the most from prefabrication, designers need to think about how the building is constructed from very early on in the process. In fact, designers need to be fully aware of just how these components are produced and the limitations of each process. It helps if designers and fabricators speak the same language. And, after realising the people, skills and knowledge problem comes the software tools problem, BIM models are rarely detailed enough to direct manufacture from, and fabricators are using solid modelling tools specifically designed for engineering fabrication and assembly. AEC and engineering tools were developed in separate silos for different audiences and deliverables.

Autodesk DfMA

Out of all the major AEC software firms that we cover, Autodesk has been the only developer to highlight digital fabrication in the construction market as being one of its key research and development goals.

It has the benefit of being a software company which caters to both mechanical engineers (through Inventor and Fusion 360) and building professionals. With decades of experience in manufacturing, Autodesk can see how that industry has progressed to digital fabrication and apply some of that technology to AEC.

Digital construction has been a topic addressed on the main stage of Autodesk University for the last few years. Company CEO Andrew Anagnost has been very vocal about the opportunity in construction to radically improve productivity and outcomes by changing the way buildings are designed, made and assembled.

Under his tenure, Autodesk has even made strategic investments in offsite / prefabricated construction firms (FactoryOS) to help understand their challenges and also carry out R&D in defining digital processes and best practices.

Looking at the Autodesk product suite, the first challenge is one of integration. While Autodesk owns both Revit and Inventor, they historically were never developed to play nicely together; they didn’t need to as they had evolved to exist in very different environments and solve very different problems.

The first I came across Autodesk admitting the two products needed to work better together was very early on, during the design phase of the Freedom Tower in New York. Back in the early 2000s, SOM was at the vanguard, trialling Revit on a massive national project.

The team started the trial on the basement and quickly decided to try modelling the whole building in, the then very formative, Revit. On top of the building was a mast containing a television antenna which was modelled in high detail in Inventor which then proved to be a problem to get into Revit at the time and needed to be worked on.

When Autodesk came to package up its offerings in Suites, some more effort was put into getting Revit and Inventor to play nicer, but this still left a lot to be desired. With Adobe’s common UI and data fluidity as inspiration, Autodesk’s plethora of design tools was always going to be a challenge and it won’t be until all Autodesk products can be delivered on the cloud, through Forge, that there will be a common data environment and a standard set of user interfaces.

While this incompatibility is there, it hasn’t completely ruled out Revit as a source for enabling digital fabrication. Companies like Strucsoft have developed an impressive array of framing, panel, truss and floor system design tools, along with CNC post processors for Revit workflows (see this AEC magazine article). Also, in the UK, Bruce Bell of Facit Homes, seen here speaking at NXT BLD, developed his own closely guarded system for generating G-code from custom parametric Revit families of wood-box parts to be cut daily onsite.

Berkeley Modular is one of the new breed of volumetric, offsite manufacturers of homes in the UK. It uses Revit and Inventor to define and drive its manufacturing process. This would not be possible had the company instigated its own software development and created custom applications to link the data from BIM to BoM (Bill of Materials).

This method uses each application for the elements Berkeley modular needs, but maintains the logic and process, external to the applications. AEC Magazine will be visiting the company this summer to have a deep dive into its bespoke development.

So, I guess what I’m saying here is that there is no single system you can buy to have a ‘DfMA’ process. At the moment it’s down to those who have the time, money and effort to define their own processes and develop an in-house system, using tools that are available today and Application Programming Interfaces (APIs). However, it is clear that Autodesk is committed to opening up the space and making this process easier.

This could be seen at virtual Autodesk University 2020, where there were a few sessions on Inventor and Revit and it was obvious that there had been a lot more work done to build workflows between them than we had seen in a long time.

Amy Marks

Autodesk’s relatively new Head of Industrialised Construction Strategy & Evangelism, Amy Marks, is an industry veteran who has owned a number of prefab / modular firms, Xsite Modular and Kullman Buildings.

I think the worst thing for us is that we’ve had a ‘cash for chaos’ mentality – we’ve had a disconnect between the silos of the different phases from design to construction

At virtual Autodesk University she had a number of video presentations. While some were reality TV style visits to fabricators getting to grips with DfMA, the most useful one gave an overview of Autodesk’s Industrialised Construction vision. This presentation wasn’t predominantly about pushing product. Instead, it really started at the base level, as an introduction to what the industry is trying to achieve.

Marks kicks off her talk, explaining the industry has a language problem – and she is spot on. She breaks down the

terminology, the meanings and the task at hand. This is a great 101 for those that want to understand the basic terminology and principles, especially about breaking down designs to assemblies.

While many see pre-fabrication and offsite as mainly being about lower costs, Marks identifies silos as a problem and project outcome ‘certainty’ as the goal of DfMA. She says, “We all recognise that there’s a skilled labour gap and we’re all fighting for the little amount of labour that’s on this planet right now. We’ve also been a little slow to digitise within our ecosystem. But I think the worst thing for us is that we’ve had a ‘cash for chaos’ mentality. What do I mean by that? I mean – we’ve had a disconnect between the silos of the different phases from design to construction.

“To operate, and we have to close those gaps, because that’s where waste really lives. The disconnect between design and construction is why we don’t have certainty of cost and schedule prefabrication…. it can eventually drive down costs, and save time for us, but we’re really looking for certainty. If you look at some of the studies that have been done, especially from the Lean Construction Institute, most of the typical projects, and even the best projects are over budget, or they’ve been late. We have to create certainty. That is the number one thing we’re looking for in industrialised construction.”

Industrialised Construction

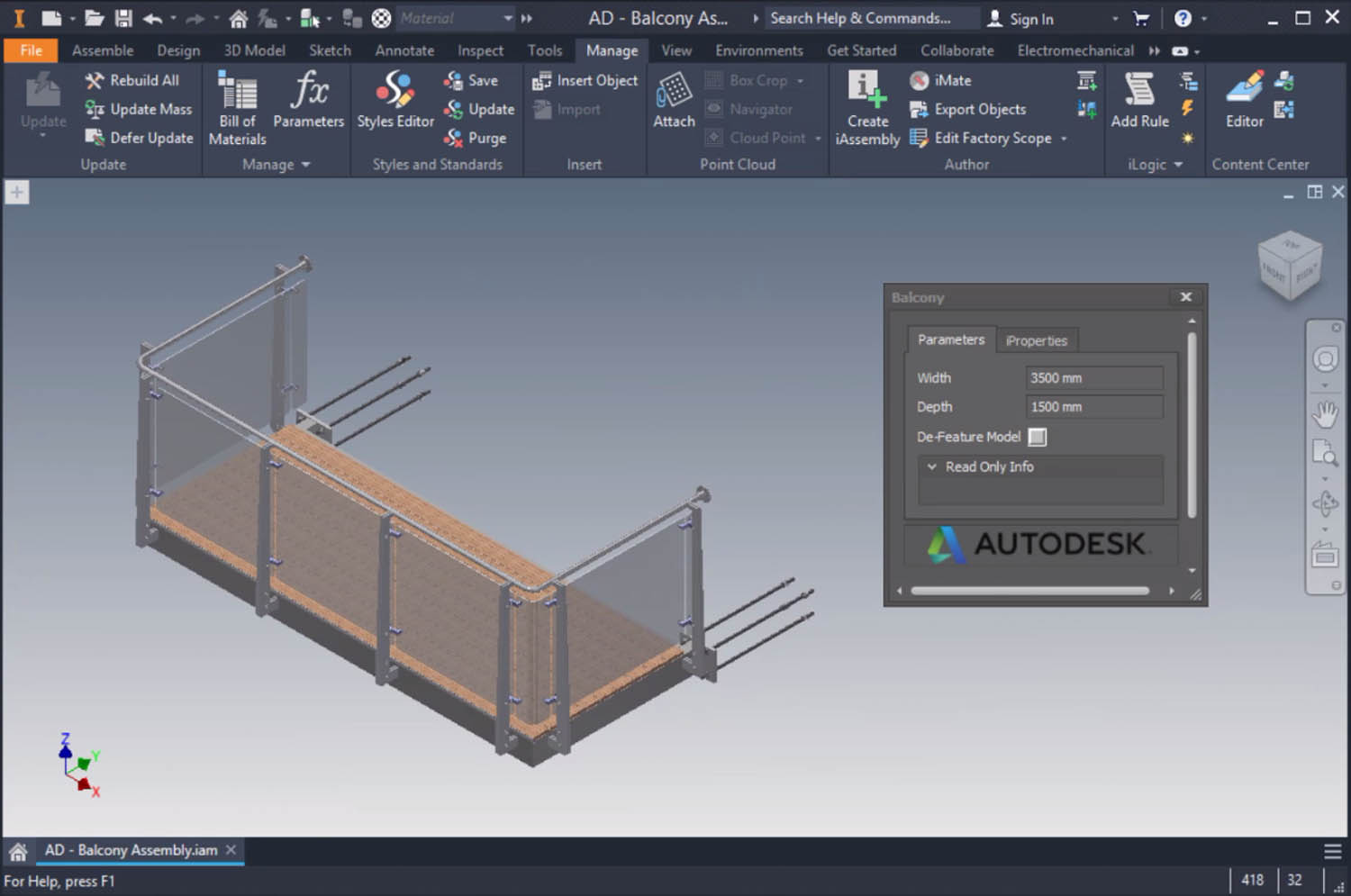

Autodesk is creating a new cloud platform for Industrialised Construction, which will be a collaborative ecosystem where Autodesk’s product portfolio and products from other vendors will be able to integrate. While the demos given concern Inventor and Revit, the reality is many firms in fabrication are using products like Solidworks to model their parts. However, Autodesk is in charge of Inventor and Revit development and can work towards them playing better together, in this case through a technology layer in the cloud.

Here, Marks explained the need to standardise design and ‘productise’, “We have to change from a project centric mindset to a product lead mindset. We need to not just take drawings and modularise them and cut them into pieces and parts that we can prefabricate (just) once or maybe like ‘the thing we did last time’. We need to define products so that we can achieve transformational change. We need to have certainty around that product. Just like a generator manufacturer makes a 200 or 250 or 300 horsepower generator, they won’t make you a 247 or a 252.5 horsepower generator. We have to productise.”

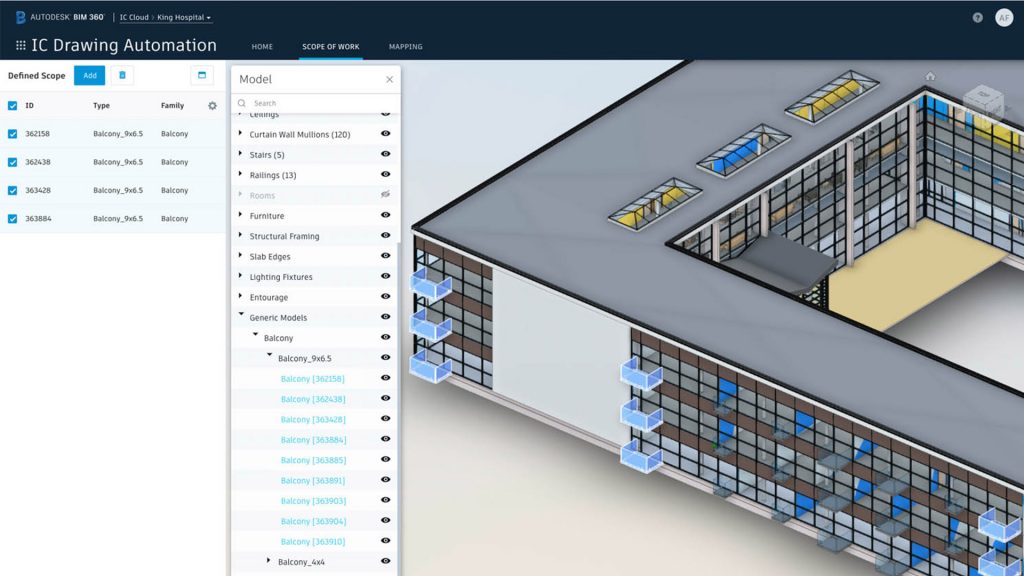

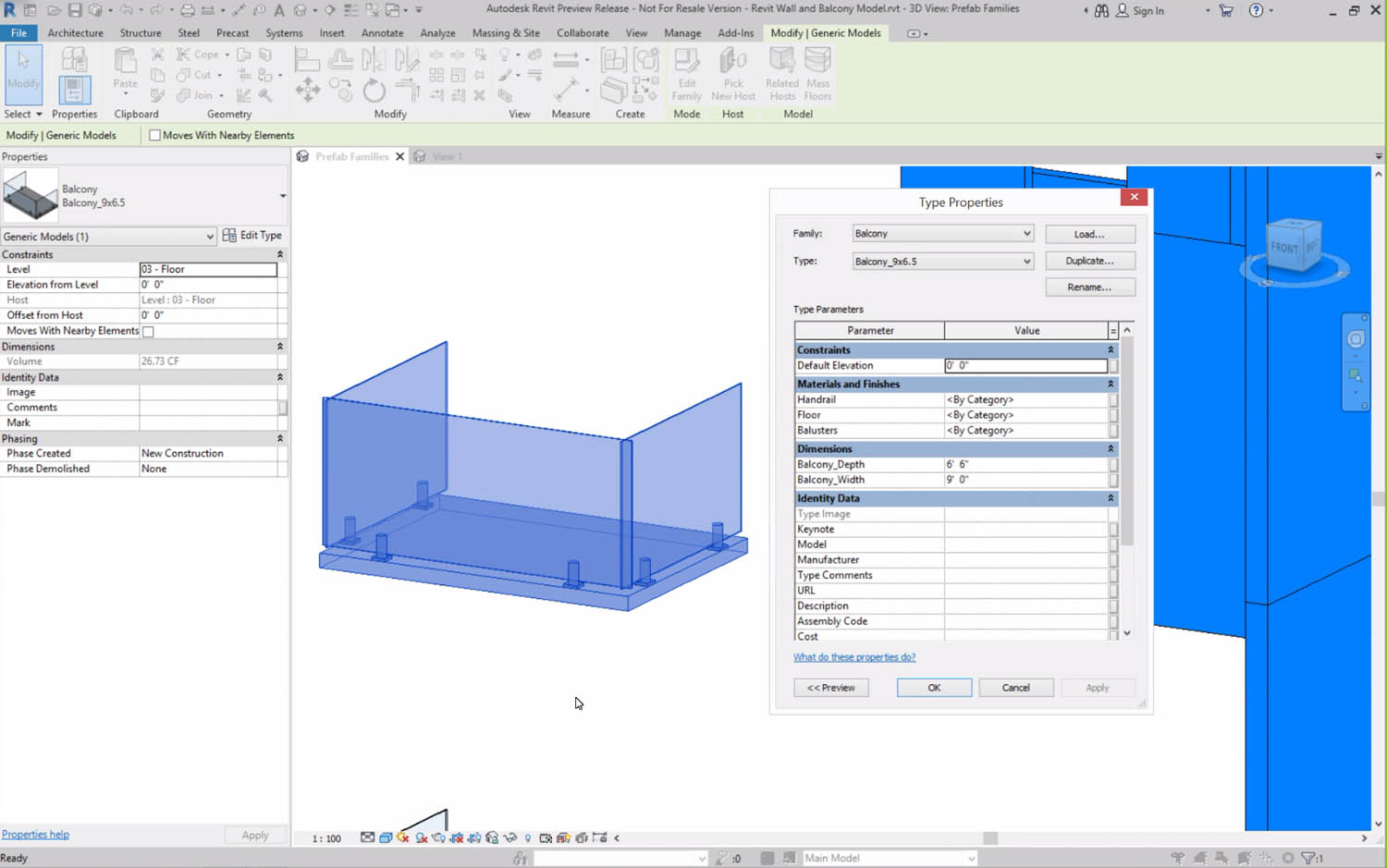

In the latter half of her presentation, Marks gives visual examples of Autodesk’s unreleased ‘Integrated Construction’ platform. This is particularly fascinating as it shows how the industrialised construction web service, takes in an Autodesk Revit model, allows the production engineer to pick the parts to be manufactured (termed Scope) from the Revit model viewer, enables easy configuration of those components through templates and automates the creation of fabrication-ready Inventor model, drawings and Bill of Materials (BoM) (this was a feature in Inventor 2021).

Marks commented that the drawing often takes longer than the fabrication of the part, automation of shop drawings. This is a very streamlined process: set inputs, define the job, get automated outputs. However, I assume it’s made easier through ‘productisation’, where an equivalent component is already parametrically modelled in Inventor. This would perhaps not work so well for unique or bespoke manufactured parts.

Future cloud Quantum/Forge

Over the last four years, Autodesk has occasionally talked about a higher-level approach to digitising the AEC process. With Project Quantum and Project Plasma, which AEC Magazine has covered in these articles (Quantum and Plasma), Autodesk promised a cloud-based system which could act as a data ‘arbitrageur’ between project team members, allowing data to go from low defined architectural models, to fully defined fabrication models.

The core issue was allowing each discipline to model in the appropriate level of detail, with their perhaps being multiple models of, for example, building facades within the system. While the architect defined the basic space and elements, the fabricator, using a different tool, could create a manufacturable version.

The system would allow the architect to view this detailed model too. A model would have interface points, where manufactured elements could be hand off points to engineering applications.

The trail of this elusive R&D development had gone somewhat cold. CEO Andrew Anagnost told Wall Street analysts back early in 2020 that Plasma had a new name, the data backbone work had been done, and the team would show something at AU 2020. While there were no obvious announcements, this demonstration of Industrialised Construction platform could certainly be seen to deliver on some of the principles the software architects told us about, although this is very much at a file level with existing desktop products.

Perhaps there has been a change of plan and Autodesk is focusing more on better connectivity between Revit and Inventor and is using its cloud platform to help smooth the data flow between project participants in a DfMA process? But ultimately Autodesk’s destination is the cloud, for both design apps and services and here it would be much easier to implement a common design environment, or at least hide all the hoops that early DfMA firms are having to jump through.

The demonstration given at AU showed how Autodesk planned to leverage the Forge components from its manufacturing development to deliver an integrated cloud service.

Conclusion

This month on AEC Magazine, you’ll find a number of voices from the industry, giving their interpretation and visions for a future fully digitised AEC industry For, example, Tal Friedman – Towards a parametric future and Richard Harpham – Design for constructability). I feel it’s becoming clear where we want to be; the issue is how do we get there?

The current generation of BIM tools was just the start of the journey. Software, company roles, individual roles, process, data and contracts will all have to change and adapt. Firms that are early in, and individuals who are willing to invest their time understanding the intricacies of off-site production, will be the winners.

AEC Magazine will be running regular coverage of this topic, as well as it being a key discussion issue at our NXT BLD conference.