In early November, Chinese drone developer DJI held its second annual US event, Airworks, in Denver, Colorado and outlined new commercial use-cases, as Martyn Day reports.

In today’s society, the idea of drones gets a mixed response. People tend to think of military uses, sinister surveillance tactics, Amazon’s work on using drones to make deliveries, or the potential risks that drones pose to commercial aircraft.

The reality is that drones are incredibly popular with consumers, but also have many possible industrial applications, most of which have yet to see mainstream adoption.

China-based DJI is the leader in a rapidly growing market for drones. According to Gartner, global drone unit sales grew an estimated 60 percent last year to 2.2 million, and revenues grew 36 percent to $4.5 billion. That market is projected to grow to almost 3 million units and more than $6 billion in revenue this year.

DJI dominates the market. Its nearest competitors can each only muster single-digit market shares. The company has over 1,500 engineers working on research and development and seems to come out with a new drone about every six months, with each new introduction making gains in terms of numbers of sensors, speed, longevity and offering new sizes and capabilities. Now, DJI is focusing on expanding the commercial use of its drones within construction, infrastructure, agriculture, public safety and energy.

In recognition of the emerging role of drones in the AEC sector, CAD companies such as Autodesk and Bentley have accelerated their development of laser scanning and photogrammetry capabilities (Reality Capture in Autodesk parlance, ContextCapture in Bentley speak), enabling the capture of as-built structures, pre-existing terrain, building sites and infrastructure.

This has led to partnerships with drone firms, such as Skycatch, which offers drone surveys, model making and data analysis based on the DJI drone platform. As desktop applications become enabled to handle 3D data that has been captured, new opportunities are opening up.

Drone use-cases take off

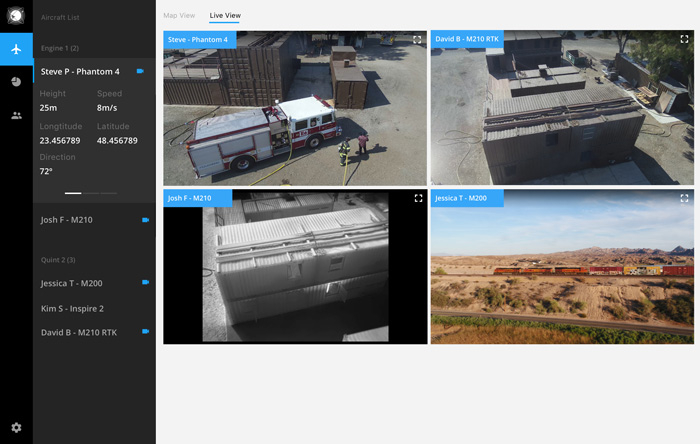

The race for new capabilities looks set to continue. With large firms now moving to deploy drones for inspection tasks, DJI has introduced a new cloud-based application called FlightHub to help keep track of pilots, tasks, drones and flight data across an enterprise, from anywhere on the planet.

Using a secure HTTPS link from the DJI Pilot application, data is sent to the cloud, where it can be remotely accessed. The cloud platform brings together flight logs, user information, real-time telemetry, an ability to see a ‘live view’ from drone cameras, together with team and hardware management tools. The subscription service comes in three flavours — Basic, Advanced and Enterprise — with prices starting from $99 per month.

While DJI has many of its own engineers working on its drone technology, the company has also recently opened up its in-flight operating system with a software development kit [SDK]. This enables third-party, custom-built applications to be run in-flight that either access sensors or flight controls, support in-flight processing of data, or permit the inclusion of other hardware, such as LiDAR systems, thermal cameras, RFID scanners or additional GPUs for on-board processing.

It would seem that this has created a burgeoning ecosystem for the developer community to build commercial applications for mission-specific uses. For example, insurance firms are keen to use drones to quickly assess damage to areas with many buildings, speeding up damage assessment, when situations such as hurricanes, tornadoes and forest fires strike, as has been so common during 2017.

US network operator Verizon has been won over by drones — so much so that it has acquired several firms that help it manage and inspect its millions of antennas and poles. That has allowed Verizon to rid itself of 30,000 inspection trucks costing $50,000 each, replacing them with an army of drones priced at $1,000 each.

For DJI, SDK usage is exploding, with over 2.7 million activations in 2017, up from 1 million last year when the kit was first introduced. The latest version allows developers to tap into drones’ visual recognition systems, helping developers code unique autonomous (in other words, self-flying) drone solutions.

The company’s heavy-duty pro drones, the Wind 4 and Wind 8, can also be customised using the SDK for more complex tasks and unique sensor payloads. The Wind 4 can lift 13.5kg, for example, while the Wind 8 octocopter offers increased stability together with redundancy.

At DJI’s Airworks conference, there was a lot of talk concerning big data and analysis. Collecting imagery is just the start of the process. While the computing power found on board the drone is focused on flying (making sure the drone doesn’t hit anything and getting it back to where its mission started) additional processing can be added and accessed via the SDK. Alternatively, the data might be sent to the cloud and processed using Artificial Intelligence (AI) solutions such as IBM Watson, in order to identify all manner of situations — landslides, escaping gases, fires and so on. Data ecosystems are now being built around drone inspection.

DJI also demonstrated an application it is developing for filmmakers to assist with pre-production and location capture. Called Project Vertex, users will be able to fly a drone over a site to capture an environment in photos that are then converted to a 3D model. Then, using the 3D model, it’s possible to examine the location in detail in real time and plan camera paths, allowing for lenses with different focal points. When the director is happy with the flight path and view through a scene, this can be uploaded to a drone, which will meticulously follow the path. This could just as easily be used on construction sites and proposed mixed reality models for architecture.

Developers get involved

A number of interesting third-party developers exhibited at Airworks, including:

Pix4D offers mobile, desktop and cloud-based solutions that will capture, process, analyse and share models for surveying, construction, real estate and agriculture. The company has a new technology, Pix4Dbim, which delivers accurate photogrammetry from drone-captured imagery, delivering precise 2D orthomosaics and 3D mesh/models using machine learning. Pix4D’s system can identify buildings, trees, hard ground surfaces, rough ground and human-made objects and, at the the click of a button, automatically classify the contents of dense point clouds into these categories.

Propeller Aero gave an interesting presentation on how it is helping landfill firms maximise the use of land with regular scanning, as well as assessing the height of landfill and calculating natural subsidence. The company offers construction firms the ability to generate topological maps, generate cut and fills and track project progress against design, measuring volumes, distances, grades and heights. Propeller Aero recently signed a deal with Trimble for global distribution of its cloud-based visualisation platform and is being integrated with Trimble’s Connected Site solutions.

Drone Deploy provides image processing, data storage, real-time sharable drone maps and 3D models through its enterprise platform. With a focus on workflows, the company provides accurate drone-based surveys, project monitoring and measurement. It also integrates point clouds with BIM workflows (it is an Autodesk Forge developer), enabling construction sites to be compared to BIM designs. The company has a free app for controlling automated flight paths, map generation and creation of 3D models, together with a portal for sharing data.

Precision Hawk has built a platform that supports both multi-rotor and fixed wing drones, together with a wide array of sensors (photo, video, 3 or 5 band, LiDAR, thermal and hyperspectral). The company enables the collection of data through autonomous drone flights, offers survey reviews in-field and rapid processing, modelling and reporting for additional analysis. Precision Hawk’s drone safety platform provides real-time airspace and ground obstacle data for drone safety, to reduce risks to manned aircraft and airports. The company also provides clients with the services of experienced pilots and data wranglers and is the only firm authorised by the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to fly beyond visual line of sight.

Legal issues

With the explosion of consumer drones and with drone flights now outnumbering commercial flights two to one, there have been some negative stories of conflicts in airspace and misuse.

This was a running theme throughout the conference: presenters from the Menlo Park Fire Brigade, for example, reported that even they had trouble getting the FAA to let them use drones to track forest fires.

The industry is keen to train and certificate professional pilots, but current laws still mean that drones cannot typically fly beyond visual range and special permission is required to fly above crowds.

There was much talk about lobbying the US government and the FAA’s work in testing drone impacts on cadavers, in order to estimate the levels of damage that a malfunctioning drone could cause. Other attendees spoke of implementing measures to liberate the market by introducing the same kind of professionalism that applies to more established forms of aviation.

In response to concerns around risk, DJI has introduced AeroScope, a ready-to-use system to enable authorities to identify, track and monitor airborne drones, especially near sensitive locations or in areas of safety concern, such as airports. The solution acts like an ‘electronic license plate’ for drones and helps to ensure they remain in safe and secure airspace, transmitting registration or serial numbers, as well as basic telemetry, including location, altitude, speed and direction. The company also is working on geo-locking technology, to prevent drones flying into commercial airspace or sensitive locations.

In the UK, the government has just announced proposals to make pilots of drones over 250g in weight take a safety awareness course and is looking to ban drones from flying over 400ft and near airports, with current limitations stating they must stay at least 40 metres from other people and 50 metres from buildings. This new legislation was based on 81 reported incidents during 2017, a figure that doubled from 2016.

Drone futures

While it’s amazing to see what drones can do today, there was one presentation in particular that looked at what might be commercially available in the next few years. DJI has invested in AutoModality, a New York-based firm that is developing an autonomous bridge inspection drone, based on the DJI platform. The new system enables fully autonomous close-up infrastructure inspection and assists workers by accessing difficult and dangerous locations on a structure on their behalf, allowing them to remain safely on the ground.

AutoModality adds additional sensors to the guards of the drone blades to help with assessing proximity to objects and utilises an attached LiDAR scanner, feeding an extra Nvidia GPU powered brain. The team built a mock-up of the interior of a bridge structure to test-fly the autonomous drone, occasionally pushing it with a stick to see if it would autocorrect. The drone flew down the narrow channel with just inches to spare.

For live trials, AutoModality first attempted inspection using manually flown drones but ‘lost’ two of these in the process. Large metal objects like bridges tend to warp the GPS signal or introduce blind spots, causing loss of control. With its new autonomous drone, the team achieved a full 70ft flight down a narrow channel on the bridge, avoiding collisions and returning with inspection footage.

One of the biggest limitations of drone technology remains battery life. By adding extra sensors and GPU processing, AutoModality shrunk the drone’s flight time to just 15 minutes. Adding extra battery capacity for longer flight times, however, is perhaps one of the biggest issues for autonomous flight. Range is limited and inspection teams are forced to fly the drone in close proximity to its target. However, like autonomous cars, autonomous drones are clearly the direction in which the industry is heading.

Conclusion

Its success in consumer drones has enabled DJI to invest in producing ever-smarter drones at remarkably low prices. But it’s a double-edged sword, with drones unleashed in airspace with no real solutions to the challenges of monitoring or tracing owners. This has left institutions responsible for airspace management playing catch-up and is inhibiting professional drone usage.

DJI is making efforts to develop controls and tools for the monitoring of drone flights, to lessen the risks they pose. With commercial drone usage predicted to grow dramatically, government agencies need to derive workable on-demand measures for professional missions.

The success of DJI’s SDK, meanwhile, is bringing tailored applications to the construction and infrastructure market, from initial site capture prior to design, all the way to monitoring assets during their lifecycle.

In many of the talks given by developers at Airworks, big data processing was one of the most common topics, with some of this work being performed on-board, but the majority needing post-processing and analysis. With the many benefits of drones comes the problem of how to handle and use all the data they generate per flight.

Looking ahead, with AI, machine learning and an increasing number of sensors incorporated into drones, the role of humans in piloting these machines is looking highly doubtful – just as we also see in driving. In other words, drones could be just another form of autonomous vehicle, operating above and alongside cars and trucks, with significant impact on our cities and their infrastructure.

According to one speaker from Verizon, the company is contemplating a future where drones act as the cell masts of a city, intelligently steering themselves to where they are most needed in bandwidth terms, rather than being located in fixed positions. In this way, if a football game, for example, increased the density of cell demand in a certain district, extra drone-based antenna could be flown in, in order to meet temporary spikes in need. Over the coming years, many other organisations may allow drone technology to take them on similar flights of the imagination.

■ dji.com

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to AEC Magazine for FREE