Prototyping using student resources, working in 3D across project phases and developing technology ecosystems for communication are helping construction teams discover innovative ways to build, writes Sumele Adelana

Architects are known to dream big. They design to inspire social change and a greener future, but it’s a contractor’s job to build those big ideas. Understanding how to move from concept to concrete pour is a creative challenge in itself. If architects are pushing the envelope design-wise, it means the contractors they work with have to push the envelope on what can be built, asking: Is the design structurally sound? How do we coordinate multidisciplinary teams efficiently? What is the best way to pour concrete for complex, organic shapes?

Construction professionals often want to try new technology workflows, but they lack the time and budget — and don’t want the owner to think they’ve wasted resources on experimentation. With little margin in the construction industry to support creativity, finding space for exploration and play within real-world deadlines and budget constraints is still possible.

Owner of RDF Consulting Services and consultant for Turner Construction, Renzo di Furia, has found that prototyping using student resources, working in 3D across project phases and developing technology ecosystems for communication helps construction teams discover innovative ways to build.

Prototype, then iterate again and again

Construction professionals must constantly learn new technologies to save time and build sustainably, but often they are stuck using old processes because it’s hard to pivot. Applied research solutions are a long-term investment that can pay off for the current project but, more importantly, can be used for future projects and scaled for large or small builds.

Working with undergraduate and graduate programs at the University of Washington, Renzo has found a way to experiment with cost-effective construction technology that gives students real world career experience. He understands that if his teams don’t continually innovate, others will, and the bottom line will suffer.

“The advancements that NASA developed to get to space created an innovative environment that has fielded a whole generation of technology,” said di Furia. “We need a similar revolution in the building industry. But it’s not just about investing in the latest technology; it’s applying technology to real problems, prototyping to create a repeatable process, and implementing adoption and learning on a larger scale.”

Students are the perfect group to test new construction technology because most grew up with smartphones and computers within easy reach; picking up new tech is second nature.

The global climate crisis will impact their generation the most, so they are motivated to find technology solutions that will reduce waste and shape a more sustainable future. Because students don’t have to unlearn outdated processes — those ways of doing things that have been around forever and are now second nature for many construction professionals — they may be more likely to embrace innovative solutions.

A catalyst for change

Professor Carrie Dossick, the associate dean of research at the University of Washington, understands the untapped potential of students. She created an educational program, the Applied Research Consortium (ARC), that benefits both students’ careers and construction professionals’ bottom line. Renzo heard about the program and immediately joined as an industry member and contributor.

It’s not just about investing in the latest technology; it’s applying technology to real problems, prototyping to create a repeatable process, and implementing adoption and learning on a larger scale Renzo di Furia, RDF Consulting Services

ARC brings together an interdisciplinary group of built environment firms with faculty experts and graduate student researchers at the University of Washington’s College of Built Environments (CBE) to address the most vexing challenges that firms face today.

The next generation of practitioners and scholars apply their creativity and knowledge of the latest practices, accelerating progress and preparing for future work at the leading edge of our fields.

Find this article plus many more in the September / October 2023 Edition of AEC Magazine

👉 Subscribe FREE here 👈

Students, Turner Construction, and the Sydney Opera House

The theory that putting students together with professionals would spark workflow innovation was put to the test in 2018. Turner Construction had just bought a new CNC machine and needed a team to try different building methods before using it on a large job with high stakes consequences.

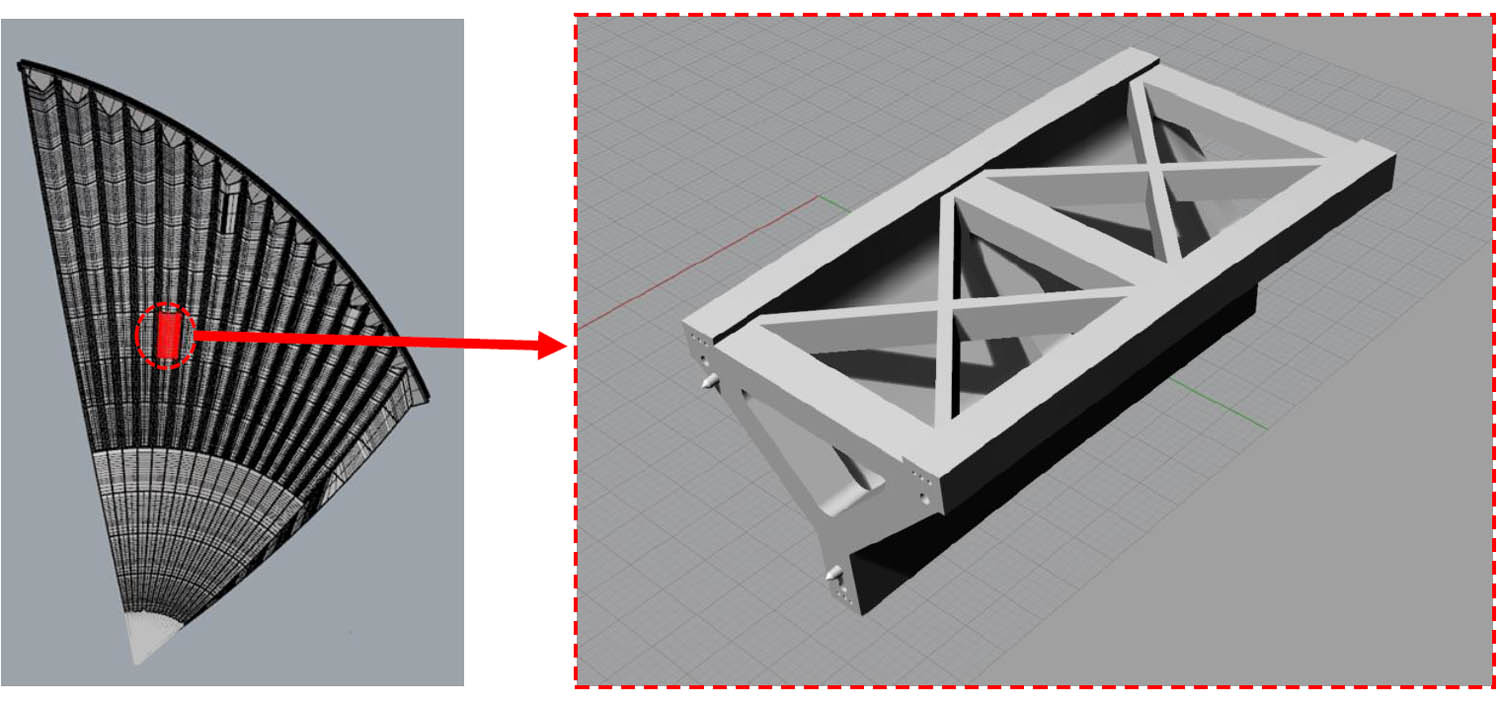

At the time, Renzo worked in Turner’s virtual design and construction (VDC) department. He collaborated with the university students to develop a better process for prefabricating formwork using the CNC machine. The team decided to recreate the famed Sydney Opera House using modern construction methods.

The performance art centre, built in Sydney, Australia, started construction in 1959 and opened in 1973 and is known worldwide for its iconic white ceramic tiled sails. The precast ribs and roof panels were all manufactured in an on-site factory, a very advanced concrete operation method for its time. Less well-known is that the construction was inundated with problems from the start. The podium structure on which the shells rest was constructed many years before finalising the structural design, which required most shell-supporting columns to be reinforced down to bedrock and caused considerable construction delays.

“There wasn’t a how-to manual that showed us how to make what we needed with our CNC machine,” said DiFuria. “It was a lot of trial and error. There are many, many complexities. We learned while tearing the machine apart and putting it back together.”

Renzo and the students began their research by reviewing the building process and finding a way to recreate it with the CNC machine. They studied the 2D construction drawings of the Opera House and translated them into a 3D model. From there, the team modelled the rebar and the formwork. Once the 3D model was created, the team successfully used the CNC machine to build the forms and pour several 1:4 scale prefabricated rib elements.

The team developed a model-based, digital prefabrication workflow from their research project. This type of work is complex and previously required high labour investments for low dollar returns. Working through how to use the CNC machine alongside other process improvements made pouring concrete more effective and helped the work fit into a manageable construction schedule. These advancements won several industry awards, including the AGC’s Build Washington Excellence in Innovation in 2018.

Building momentum

While at Turner Construction, Renzo worked with the ARC to develop a continuing education course called Virtual Modelling for Digital Fabrication, which aims to give students an even deeper dive into modelling for digital fabrication. It touches on core elements of the digital fabrication toolbox: laser scanning for reality capture, referencing historical documents, advanced model building, file formatting for laser cutting, CNC routing, and 3D printing. With the development of this curriculum, current and future students can practice real-life, advanced model-building and problem-solving for new prefabrication technologies as they come along.

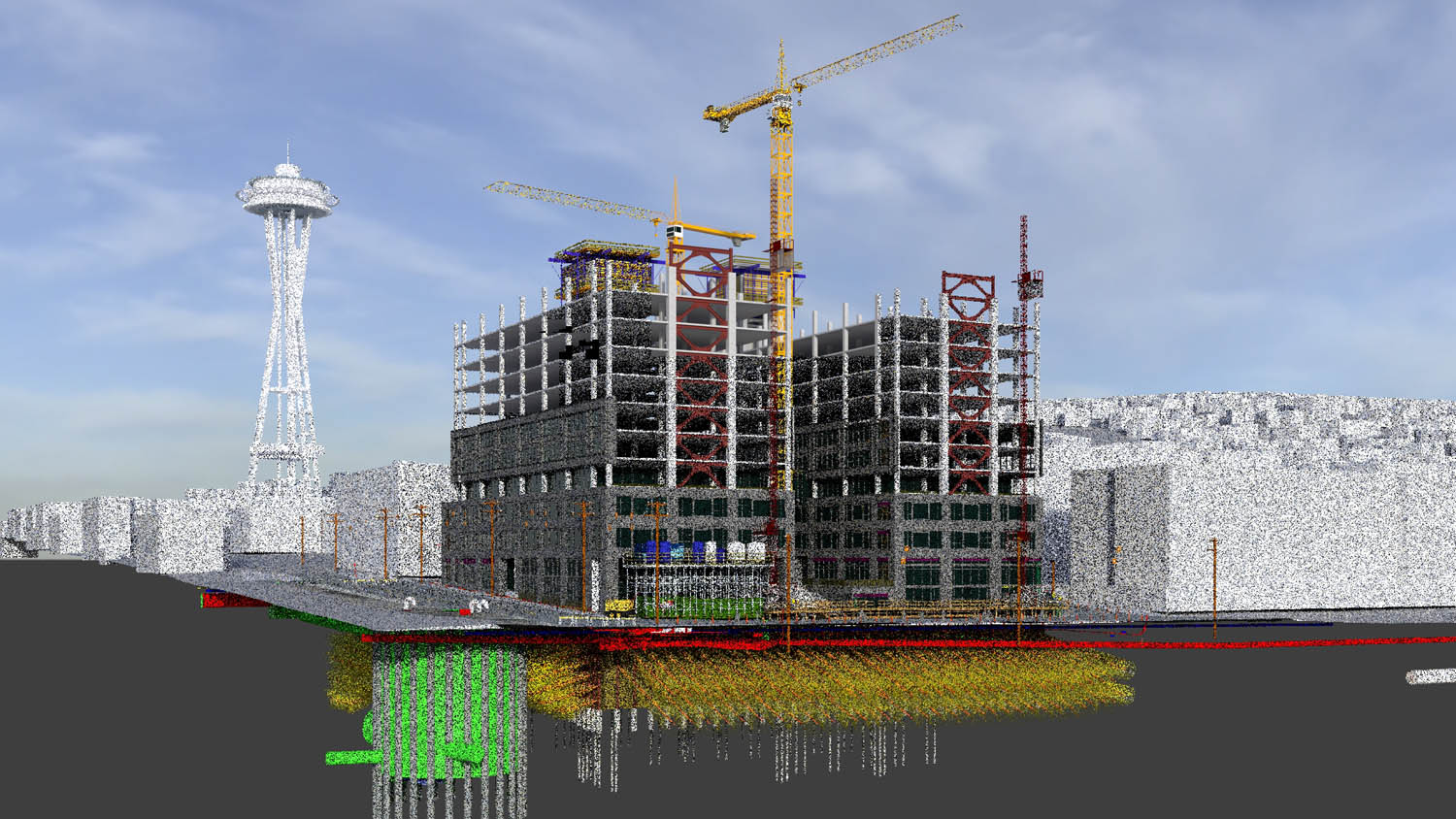

Using Trimble SketchUp for 3D modelling and Scan Essentials to import point clouds, students taking the course learn how to model a historic building. This course is ideal for students who want to learn more about design-build management or want to learn practical skills that could help them move into a related role.

SketchUp provides software for students to use and instructional videos. This program is another positive outcome of partnering with the University of Washington and supports Renzo’s assertion that creating an authentic, research forward environment must include both learning and teaching.

Applied research

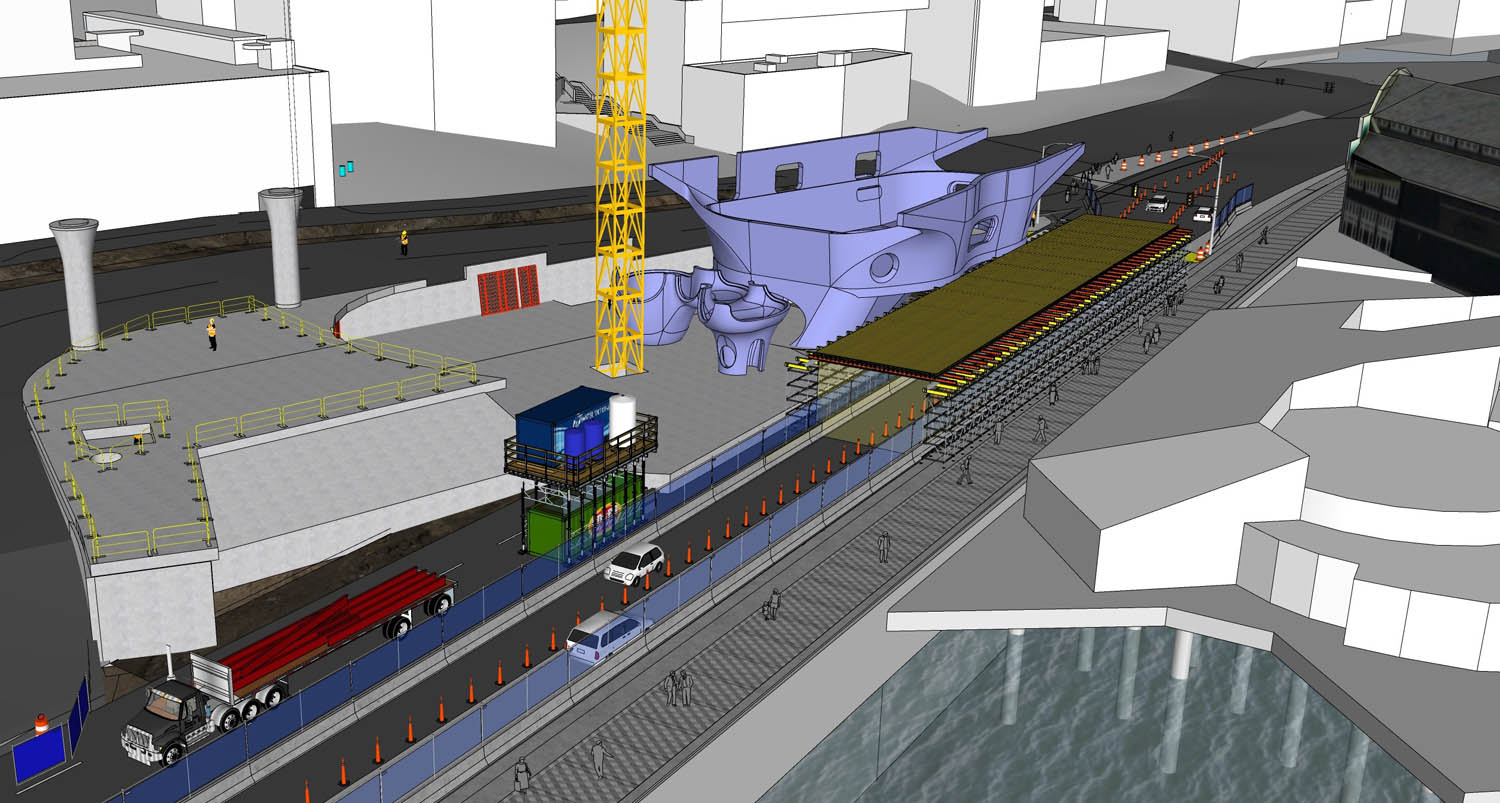

The learnings discovered on the re-modelling and quarter-scale casting of the Sydney Opera House ribs have since been applied to many different projects, including the large-scale renovation of, and addition to, the Seattle Aquarium. Constructed in 1977, Seattle’s central waterfront Aquarium has become a wellknown destination for locals and tourists.

The Aquarium’s expansion will accommodate a larger marine habitat to meet current and future demands. Turner Construction was hired as the primary contractor, and in November 2022, the company completed a more than 23 consecutive-hour concrete pour for the new habitat.

“Everything we learned exploring the Sydney Opera House, which was about a two year discovery period, we applied to the Seattle Aquarium: how we modelled the structure, how we modelled the rebar, how we approached the formwork, and more,” said di Furia.

Part of what made the habitat so tricky to build was its organic shape that draws inspiration from the ocean and offers visitors striking views of its aquatic inhabitants. Since the planned habitat was enormous, the team knew rebar constructability would be challenging. The unique, fabrication level modelling workflow was developed by Turner in-house. The structure has a two-foot-thick, curved concrete wall, 355 tonnes of rebar, and 680 cubic yards of concrete, which is about four times the rebar used on a typical core, according to Turner. The concrete form liners were constructed using structural foam with a fibreglass coating.

The foam was carved directly from the 3D model using large industrial CNC machinery. Formwork for window openings, the circular stairways, and the dramatic entrance oculus was produced using digital fabrication methods in Turner’s fab shop.

The previous research that students and Turner had done on parametrically modelling complex, organic concrete geometry, rebar constructability, and digitally fabricating formwork using CNC machines helped the team tackle the unique build for the Seattle Aquarium, saving significant time and money.

Adopting 3D from start to finish

One of the challenges in construction — and one of the reasons it’s so expensive — is the job teams can be massive, and there is a lot of information to process. You’ll often hear about siloing problems between architects, contractors, and owners. What’s less common is to hear about the silos within construction teams.

You could have fifty trades on a job site, each needing materials and equipment at a specific time. Valuable time and resources are wasted if these needs are not coordinated effectively.

“Building a sound 3D model that you can use throughout the design and construction process takes quite a bit of practice and dedication — a little bit like learning to play a musical instrument well,” said di Furia.

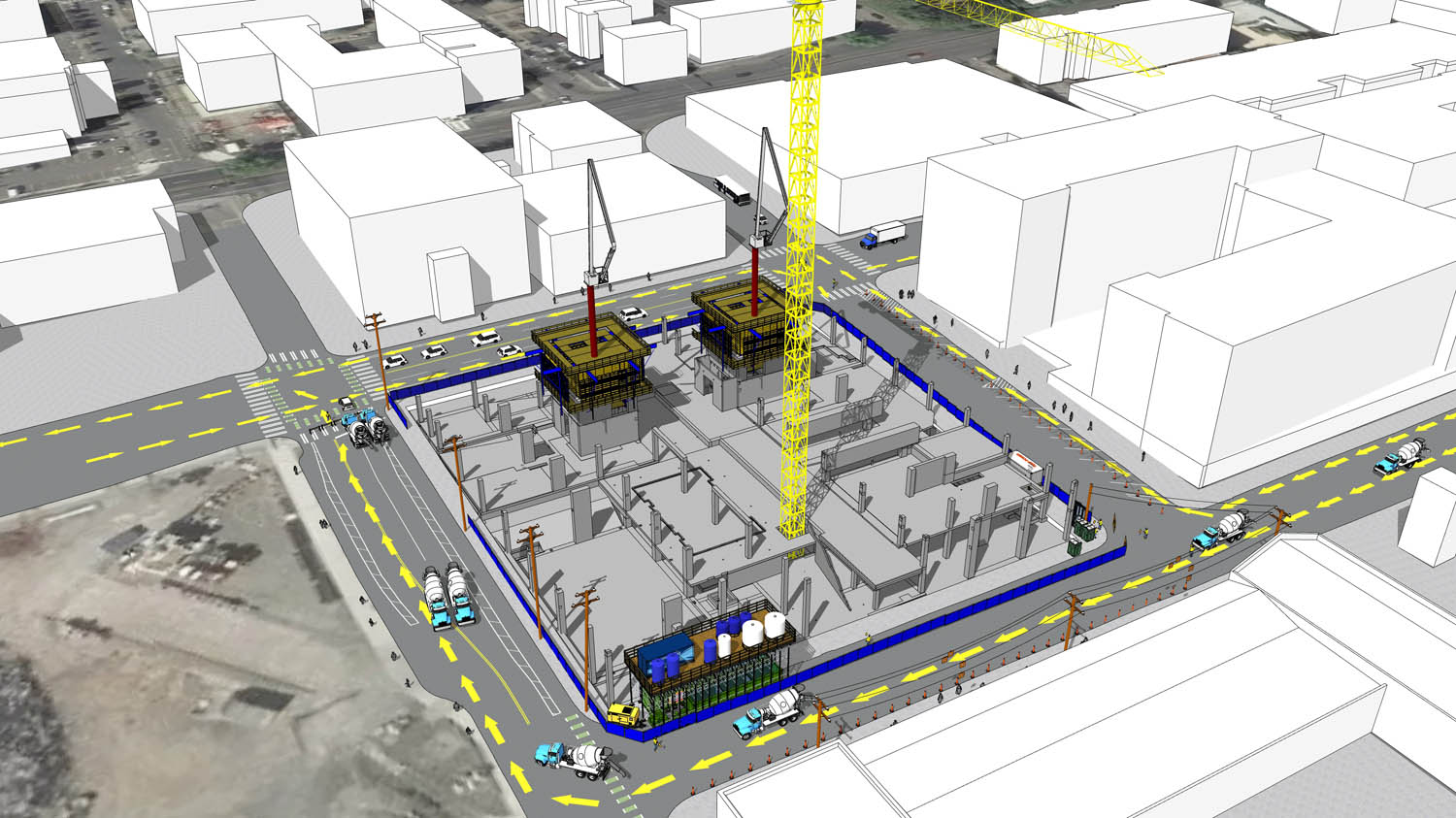

Renzo and Turner leveraged data in a 3D environment for the Seattle Aquarium project to improve collaboration across teams. It’s now the first project that Turner has done using 100% model-based communication from start to finish. Renzo and the Turner team used a SketchUp model with hundreds of scenes for site planning.

Later in the construction process, they pulled all the material amounts from measurements in the 3D models of the habitat, which included a 3D model for concrete, wood, and rebar.

The habitat was first mocked up with a physical foam model — carved with a giant CNC machine — a later iteration of the process the students developed studying the Sydney Opera House.

“For the Seattle Aquarium, the complexities of the design pushed the site management to adopt a complete 3D workflow, which broke down information silos and allowed any puzzles to be solved by a much more unified team,” said di Furia. “The ability to problem-solve effectively with a large, disparate group is rare and demonstrates the enormous value of a true 3D process.”

Having a 3D model updated from the beginning of the process through construction kept an open line of communication with all stakeholders. Turner’s team met with the architects and other disciplines once a week to review the 3D model and solve any challenges.

An interconnected tech ecosystem

Interoperability between design software was just as important as communication between people on the project. The team used Trimble Connect, a cloud-based common data environment (CDE) and collaboration platform created to keep everyone connected with synced model versions.

In addition to Trimble Connect, the team used SketchUp for 3D modelling, LayOut for generating 2D documents, Tekla for structural design, Trimble Total Stations and Trimble Laser Scanning Solutions for surveying, Revit for detailed construction documents, and more.

“We began our VDC journey years ago by coordinating MEP systems,” said di Furia. “We then took those lessons and applied them to our self-performed concrete operations. During that discovery process, we realised that the true critical path of any construction project is information management. I’ve since been prototyping an improved structural-centric workflow system that increases quality control dramatically and can be applied to any project, large or small.”

For the Seattle Aquarium, the complexities of the design pushed the site management to adopt a complete 3D workflow, which broke down information silos and allowed any puzzles to be solved by a much more unified team

Using the right technology at the right time levelled up Turner’s modelling and coordination for the Seattle Aquarium, strengthening the quality control processes and helping manage all the information shared throughout the design and construction process.

Structure-centric systems

The construction industry is moving into a new era of collaboration, and there will be new technologies and processes to adopt. Renzo believes moving toward structure-centric systems will improve coordination and bring model information together.

“ln all the years that I’ve been doing this [VDC Management], we start with MEP coordination and then apply that to our self-performed concrete operation,” said di Furia. “I believe there’s a better way; I’ve prototyped a structure-centric workflow system to help bring data and disciplines together, following one centralised structural model.”

Creativity and construction go hand-in-hand

The construction industry still has enormous challenges with workflow disconnects, finding ways to apply new technology, and teaching its adoption across teams — challenges that need to be overcome to build a better and greener future.

Construction professionals, it’s time to show how creative you can get when building. Contact your local university to connect with students looking for their next thesis topic.

Research and replicate innovative solutions on smaller projects first, and then combine what you learn with advanced 3D workflows and intelligent technology to build projects more quickly and efficiently. All this will inspire a culture of learning in your company that reduces waste and is better for the environment. Let’s show the next generation of engineers, contractors, and consultants that thinking of outside-the-box solutions is just as crucial for future builders as it is for future designers.

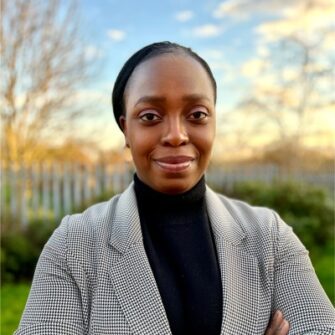

About the author

Sumele Adelana is a Nigerian-British architectural designer, thought leader, and product specialist at the 3D modelling software company Trimble SketchUp. Sumele became an associate member of the RIBA after completing her undergraduate and postgraduate education in architecture at the University of Portsmouth and Kingston University in 2009 and 2012. She has interned at reputable architecture firms such as James Cubitt Architects, Foster and Partners, and worked at boutique design-develop firm Whitebox London after receiving her interior design certification at the KLC School of Design.

Main image: Renzo di Furia worked with students at the University of Washington to research how the Sydney Opera House could be built with modern technology and applied those workflow learnings to new projects