Architects are using daylight analysis to better tell the story of a design to clients. Together, renderings and analysis build a more complete — and more compelling — case for design, writes Carl S. Sterner.

As architects, we are trained to use daylight to shape the character and experience of the spaces we create. We are skilled at exploring the visual, experiential aspects of daylight. We are adept at creating striking renderings — those beautiful depictions of light and shadow that viscerally communicate the character of the design. These images are easily woven into the narrative of our design intent, and easily understood by clients.

But there is a critical element missing from this medium: the practical issue of whether the daylight actually works. Are our renderings actually representative of the lighting in the space, or are they evocative works of fiction? Do they capture typical conditions or a unique moment? Does our design actually supply the lighting required?

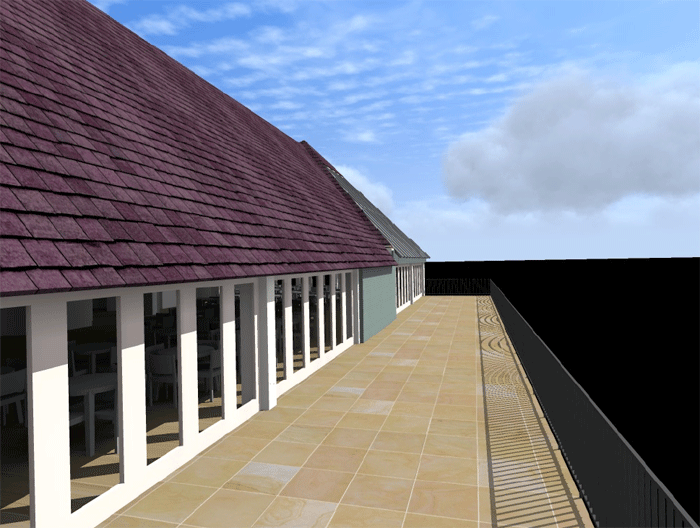

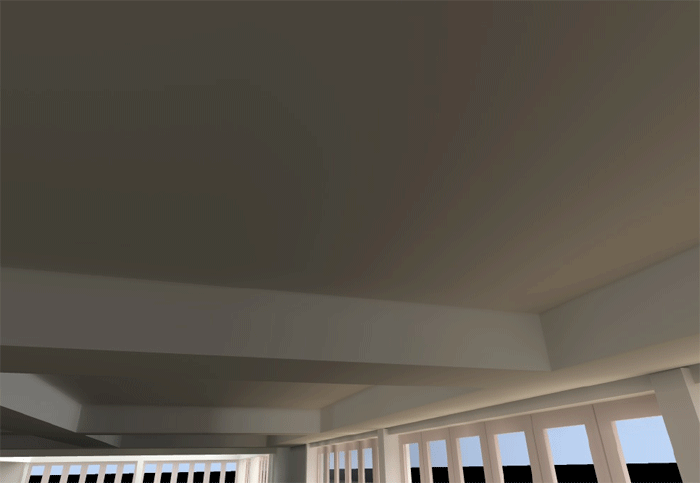

As-existing CGIs

Renderings are unable to answer outcomes-based questions: Is this classroom well-lit for most occupied hours? Is there glare in the conference room? Are roof lights an effective strategy for improving day-lighting in our office? How do they compare to light shelves? Should there be more glass on the north or south façade? A good design needs more than poetry: it needs to work — not just sometimes, at that magic golden hour, but every day, every hour.

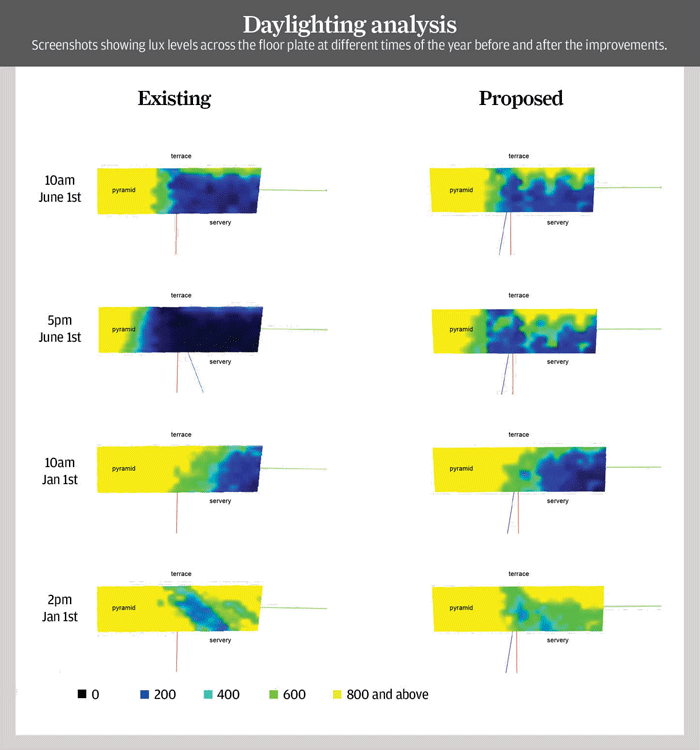

These are questions, of course, for which daylight analysis is well suited. Nearly every space has lighting requirements, and day-lighting analysis can show how well a design meets those needs. It can help designers proactively identify problem areas, measure progress toward project goals, and compare design options. Physics-based analysis allows designers to build performance into the very fabric of their designs, and thereby weave a strong objective case into each concept.

This insight is increasingly easy to get, thanks to new tools that make daylight analysis accessible, quickly enough to be an integral part of the design process.

But the point is not simply that daylight analysis can be a great design tool (although this is certainly true). The point is that it is also a great tool for communication — for telling the story of a design to clients. The combination of qualitative and quantitative elements is especially powerful. Renderings put an expressive face on otherwise opaque numbers; and analysis backs up the vision with clear, impartial data. Together they build a more complete — and more compelling — case for a particular design.

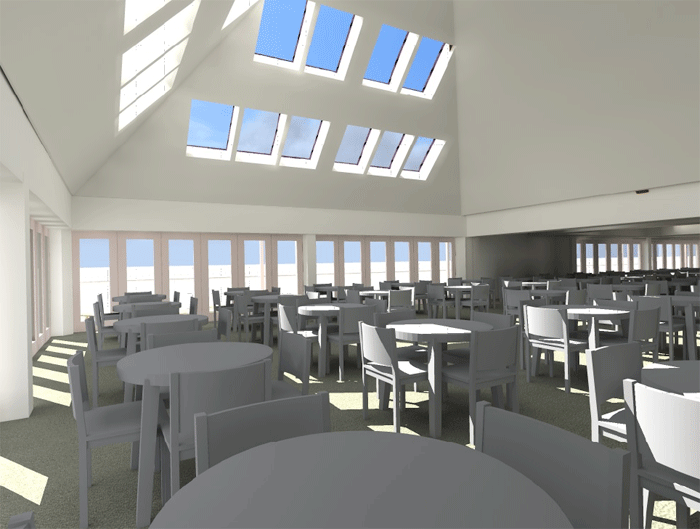

Proposed CGIs

Take, for example, a recent project by Allan Joyce Architects (pictured). The firm was approached to retrofit a Tearoom at the Royal Horticultural Society Gardens in Harlow Carr, UK, with an eye toward improving day-lighting and comfort. The building’s existing south and west glazing took advantage of views, but contributed to uncomfortable overheating and unfavorable glare. The architects developed a series of changes that they believed would greatly improve the occupants’ experience — but wanted to bolster this intuition with metrics. Their presentation put renderings and analysis side-by-side to communicate the impact of their proposed changes, both qualitatively and quantitatively. The renderings suggested an experience that was confirmed by the data.

“Our client wanted to understand in detail how the proposed changes would provide the outcomes that they were after,” Toby Evison, architect at Allan Joyce Architects said. “We used a combination of rendering and analysis software to produce a report documenting the before and after conditions. Our client was delighted — they could easily comprehend the effect of the design proposals and this directly informed their decision making.”

Mr Evison sees analysis as an important tool in the architect’s kit: “As architects working on a wide range of projects for an equally wide range of clients, it is important that we can draw on a comprehensive set of tools to communicate our ideas.”

Architects are in the unique position of articulating the vision of a design while attesting to its technical feasibility and ultimate performance. The right combination of tools and imagery allows us to speak to both aspects of design, and to weave them together into a rich and compelling narrative. ■ sefaira.com

About the author

Carl S. Sterner is a senior product marketing Manager at Sefaira and Owner at Sterner Design. He has worked at numerous architecture firms, including William McDonough + Partners.

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to AEC Magazine for FREE