From laser scanners and drones to the cloud and ‘optioneering’ it has never been easier to capture exisiting site conditions and explore new designs. By Randall S. Newton

If it has been a while since you thought about site work, and what it takes to get the information you need from a site to plan a building or infrastructure project, I hope you are sober. Because there is a dizzying array of new and improved technologies, as well as things you probably never thought would be part of construction site design. If you had a three-martini lunch today, you better read this some other time.

First of all, scanning to create terrain models for design is getting big. Prices are coming down rapidly, and quality is continuing to rise. It is no longer necessary to spend £100,000 for a terrestrial scanner (but you can if you really need the top end).

Total stations, those ubiquitous threelegged devices surveyors take everywhere, can communicate with iPads. All the major CAD design applications can work with point clouds, the data gathered by scanners; processing those millions of tiny three-dimensional points of light (called “voxels”) is no longer the computational nightmare it was a few years ago. Drones are a thing for gathering site data. And so are smartphone cameras.

All vendors involved in this new world of rapid site design agree there is value galore in the new ways of data gathering.

“Being able to create accurate ‘as-is’ infrastructure models using point clouds makes it easier to analyse different roadway construction staging scenarios,” says Karen Weiss, P.E., senior industry strategy manager for infrastructure owners at Autodesk. “Precise co-ordination of the existing environment and the new design has become vital in crafting staging that minimises disruption of service.”

What follows is a roundup of various new and/or improved ways to gather site data and turn it into design data.

Point clouds arise

LiDAR is the most common term today for the various remote-sensing technologies that illuminate a target (usually with a laser) and analyse the reflected light. The points of light are collectively known as point clouds. LiDAR data collection includes scanners in aircraft, satellites, railcars, and vehicles as well as tripods and other stationary installations. A common approach to LiDAR use today is to capture everything in sight and then assemble the data into a point cloud. A few years ago that would have been crazy, but today’s faster computers and new software algorithms make it feasible.

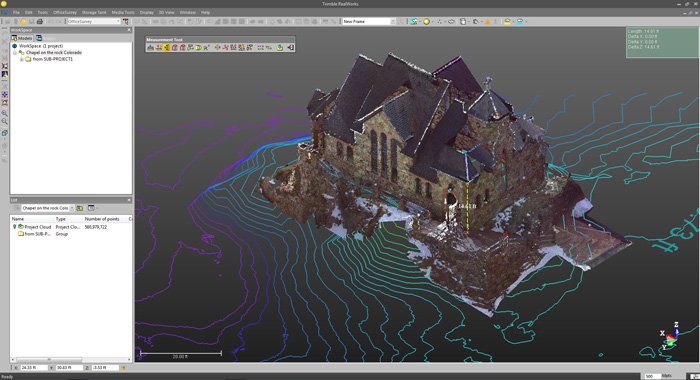

As LiDAR technology continues to evolve, the focus has shifted from gathering data to efficiently managing, analysing and utilising the large 3D datasets collected by airborne and terrestrial scanners. Technicians use processing software such as Trimble RealWorks to combine data from multiple scans into a cohesive data set, removing noise, superfluous points and outliers as part of the quality control process. We are not at the point of tossing flying balls into a cave to get a 3D map in real time, like in the 2012 movie Prometheus, but it feels close.

Who needs this data?

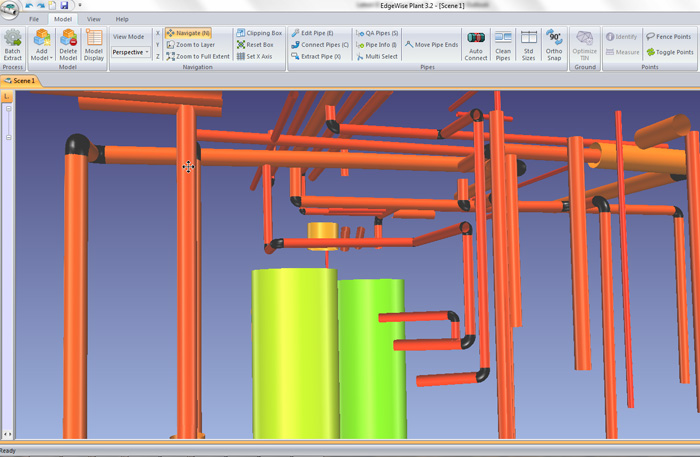

There are basically three client groups for this data. The first are those who want visualisation and basic measurements from orthoimages or point clouds, primarily planners and architects or engineers working up project presentations. The second client group are those who want the 3D data for design. A third group consists of industrial construction clients who turn to service providers to provider ready-to-work datasets of the very largest projects, such as process/power plants and major civil engineering or infrastructure projects. Sometimes this last group works directly in the point cloud data without converting to CAD.

“In the past, the bottleneck was always in the back office — 3D modelling was largely a tedious manual process,” says Chris Scotton, president of ClearEdge3D. His company offers products that turn scans into useful models with as little human intervention as possible. “New technologies such as automated feature extraction, object recognition and pattern recognition are propelling the industry closer to that mythical one-click model. We may never fully get there but we’re certainly leaping forward.”

The latest twist on gathering large volumes of terrestrial data is the use of drones (AKA Unmanned Aerial Vehicles or Unmanned Aerial Systems).

Construction data specialist Trimble has recently added drones to its product line-up. The Trimble UX5 UAS is commonly used to survey larger areas in applications such as agriculture, open pit mining, landfills and large construction sites. Rotary-wing aircraft including the Trimble ZX5 multirotor UAS are suitable for smaller sites and applications such as façade measurement or facility inspection where aircraft agility is needed.

Terry Bennett is a senior civil infrastructure strategist for Autodesk: “The ability to have personal aerial tools to capture project details is just amazing; it is redefining workflows and how we capture information. I have personally used UAS solutions on a couple of projects where we were able to fly the site in one hour, and then process that into a 3D model using more than 200 aerial photographs,” says Mr Bennett. “And the result has the same digital fidelity as if you had surveyed the site by hand.”

Photographs join the club

Yes, he said photographs. Not only are LiDAR scans more affordable and more popular than ever, but software breakthroughs have made it possible to extract useful 3D data from standard photographs. Autodesk has several products for turning photographic images into useful 3D data, some of it aimed at product development or unconventional applications such as archaeology. ReCap is an Autodesk product that works with most of its design portfolio, using cloud-based data processing to turn both LiDAR data sets and photographs into accurate 3D scan data.

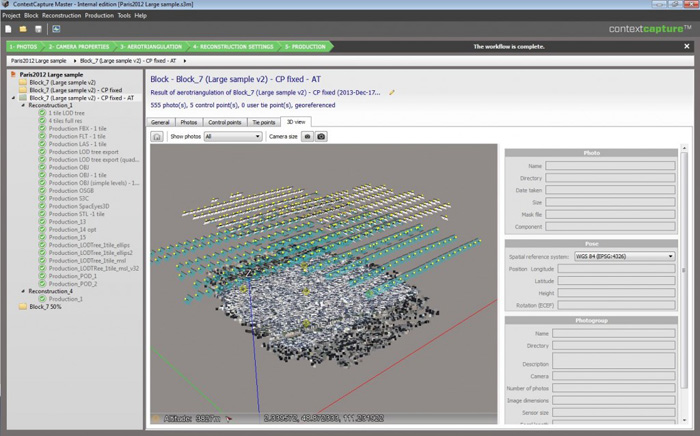

Bentley Systems is also keen to make the most of this new world of rapid site data gathering. At its recent Year in Infrastructure conference in London, it showed off a new line of ContextCapture technology, which can vacuum up all the site data you can throw at it. One recent project was the creation of a 3D model of Pope Francis’s motorcade route through Philadelphia. Bentley executive vice-president Ray Bentley led the effort to create the visualisations, and said afterward even though he understood the capabilities of the software, it impressed him to see what it could accomplish in such a large-scale task.

The software generates a detailed reality mesh incorporating referenced photography. The result, Bentley says, is a navigable 3D model with fine and photorealistic detail, sharp edges, and precise geometric accuracy. These highly detailed models can be of virtually any size or resolution, up to city scale, and he says can be created much more quickly than with other technologies.

Bentley also offers Siteops, cloud-based software to use imagery as source material for exploring countless engineering options. Users can “optioneer” virtually unlimited layout, parking, grading, and drainage options for a site within hours.

Autodesk’s Mr Bennett puts this kind of visible and functional site information into perspective: “The ability to scan a site in a matter of hours and then immediately have all the information, and not miss anything the eye can see, streamlines how fast you can get site designs up and running in a 3D modelling application, to start doing alternative design “what if ” explorations or to check quality of construction during construction.

“After the project is completed, the model and point cloud data can be used for asset maintenance going forward, for example with a civil infrastructure project, to check for any movement, shifts or changes to the site or structures over time.”

This article is part of an AEC Magazine Special Report into the Future of Building Design, which takes a holistic view of the technologies and processes, which are set to change and enhance the AEC industry in the coming years — from concept design all the way to construction.

Click to read the other articles that make up the report.

1) Introduction New technologies are empowering architectural firms to improve quality, capabilities and process.

2) Conceptual design There are a whole host of digital tools for early stage design experimentation.

3) Rapid site design The rapid capture of site topology is being aided by new technologies.

4) Benefits of 3D design Evolution, not revolution when making the move to 3D CAD.

5) Moving to model-based design How to get from 2D to 3D, how to roll out training and how to overcome common issues encountered along the way.

6) Design viz Advanced new rendering technologies are opening the door to design realism in architectural workflow.

7) Design, analysis and optimisation Once you have a 3D CAD model, optimse your design for daylighting, energy performance and much more.

8) Collaboration and model checking How to share models with clients, contractors and construction firms and test the quality of your model.

9) Workstations What to look out for when choosing a workstation for 3D CAD.

10) Virtual Reality New technologies are now available to support powerful new design workflows.

11) 3D printing Architects are 3D printing architectural models with impressive results.

12) Fabrication As building time gets compressed what will revolutionise fabrication and construction time?

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to AEC Magazine for FREE