Reality capture and surveying have undergone considerable technological changes in recent years, shifting from total stations to drones, from LiDAR to photogrammetry. Now there’s a new kid on the block, as Martyn Day reports

Reality capture is no longer a trade-off between precision and whatever you can grab before the concrete starts to pour. We now have survey-grade terrestrial LiDAR, photogrammetry from drones that can be flown multiple times a day, and SLAM scanners that happily thread their way through congested interiors, conveyed either by human or robot. We’re not short of options; the real challenge is understanding what each method can and cannot deliver in terms of accuracy, repeatability and effort.

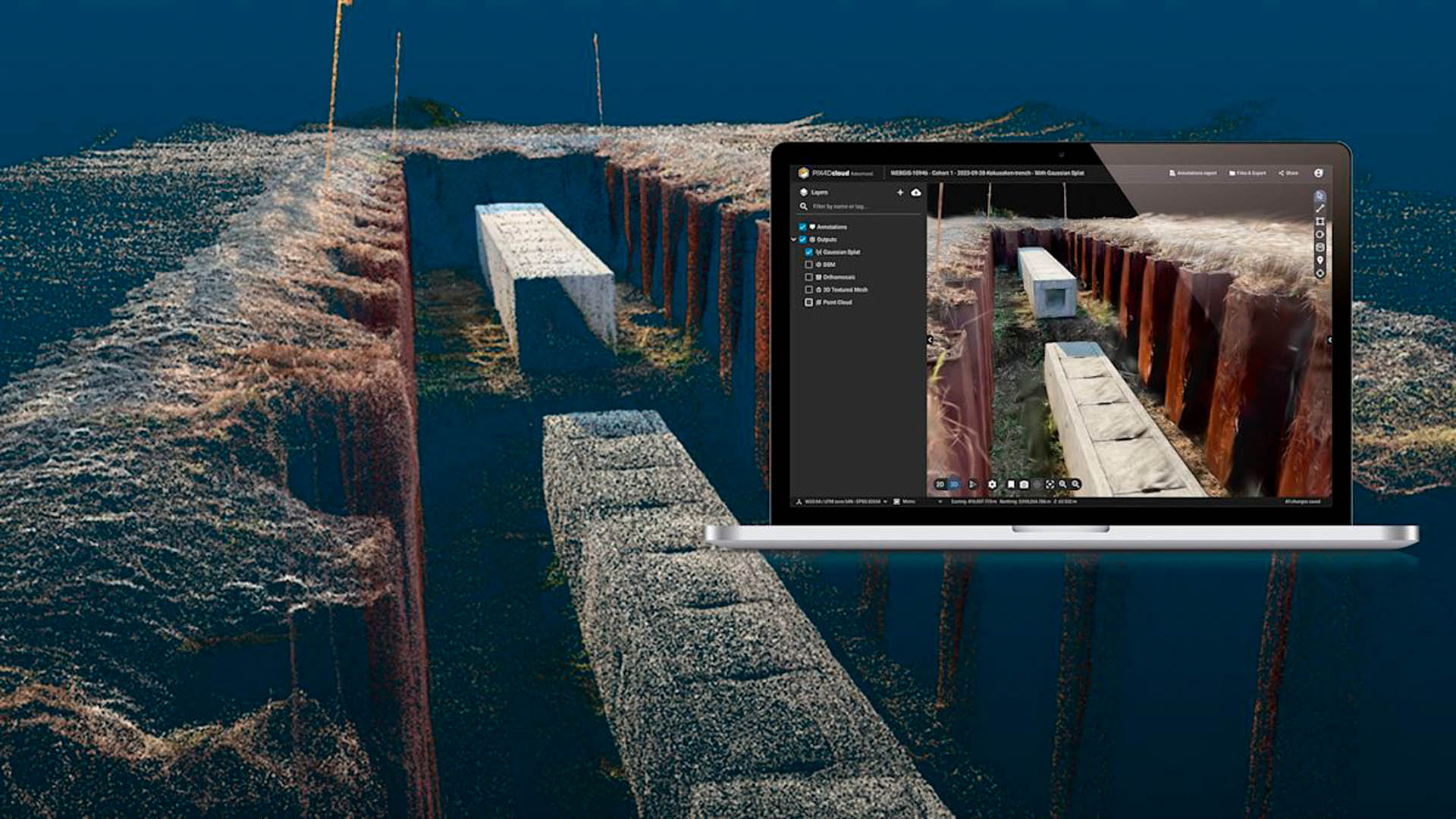

Into this already rich toolbox comes a technique from the computer-graphics world that doesn’t sit neatly alongside any of the above technologies. 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) may sound like an upgrade to paintballing, but ‘splats’ are rapidly becoming a favourite way to generate photorealistic, navigable 3D scenes from kit no more exotic than a smartphone or drone-based video camera.

The question for customers from the AEC industry is whether this is simply another visualisation fad, or the start of a more profound shift in how we capture existing conditions.

Gaussian Splats discussed at NXT BLD 2025

Watch the full presentation here

Splat origins

The core idea behind Gaussian splatting is surprisingly straightforward. Instead of building a surface out of triangles or locking yourself into the sparse geometry of a point cloud, a splat scene is reconstructed from countless semi-transparent ellipsoids (‘splats’), each defined by a position, a radius, a colour and a fall-off.

When rendered together, to human eyes, splats form a continuous, volumetric impression of a space. The technique avoids the brittle edges and broken surfaces that often plague photogrammetry, while also sidestepping the enormous compute required to render multi-million-triangle meshes in real time.

The origin story is tied to a technology known as Neural Radiance Fields. These NeRFs gained mainstream attention because you could take multiple still images of a scene and synthesise a 3D model from it, even with ‘unseen’ viewpoints. This was done by training a neural network to understand how colour and density vary with camera position.

NeRFs are impressive, but painfully slow to train and far too heavy for interactive use. Chipmaker Nvidia played a major part in pushing NeRF research into the real-time domain, producing vastly accelerated pipelines, sample code and CUDA-optimised implementations that made these once-academic models accessible to industry. Their development accelerated and the quality of the output improved (less artifacts), as well as reducing the number of images required to derive a scene.

Gaussian splatting emerged soon after as a more pragmatic alternative to NeRFs. Instead of encoding the scene inside a neural network, it takes a direct optimisation approach. As a sparse ‘structure-from-motion’ or ‘multi-view stereo’ (MVS) solution, splatting takes a collection of overlapping images and generates a 3D model by estimating camera positions and creating a dense point cloud of the scene. The software then refines millions of Gaussian primitives until they collectively match the available imagery. Nvidia again accelerated adoption by releasing reference implementations and GPU kernels that demonstrated how efficiently splats could be rendered when mapped properly onto modern hardware.

The key breakthrough is speed. A contemporary GPU can navigate a dense splat reconstruction with minimal latency, producing an experience closer to exploring a game environment than wrestling with a stitched mesh or a heavy point cloud.

This performance is the main reason why splatting has become the preferred method in consumer capture apps and early Gaussian-based AEC tools: it delivers high visual fidelity without the processing overhead and fragility that characterise many photogrammetry workflows.

It is important, however, to be clear about what Gaussian splats are and what they are not. They do not form a mesh and they are not collectively the same as a conventional point cloud. Instead, they occupy a middle ground: a radiance field with hints of geometry.

For engineering applications that raises familiar questions about scale, measurement and reliability. In practice, splats excel at appearance rather than precise geometry. When anchored to LiDAR or SLAM, they can behave well, but on their own, they remain a visual rather than a metrical representation. Context and workflow determine whether they are merely informative or can be relied upon as part of a survey-grade solution.

Discover what’s new in technology for architecture, engineering and construction — read the latest edition of AEC Magazine

👉 Subscribe FREE here

Onsite work

Because of its lack of accuracy, Gaussian splatting has found its quickest uptake not as a survey instrument but as a rapid capture method for documenting change on construction sites.

The workflow feels closer to filmmaking than scanning. A site engineer walks the site with a phone, or a drone traces its usual arc. The resulting video is ingested by a cloud service and, minutes later, a navigable 3D scene appears in the browser. The entire ritual is far lighter than a laser scan and far less formulaic than a structured photogrammetry approach.

The results sit somewhere between a video and a model. You can step through time, drift around a floor plate, or zoom into areas that would be illegible in a mesh. For project teams attempting to understand sequencing, clashes or the general state of play, the immediacy is valuable. It becomes a quick way of capturing as-built conditions on days when you wouldn’t dream of mobilising a scanning tripod.

But splatting is also being combined with more traditional methods. Several firms pair handheld SLAM devices with 3DGS reconstruction, using a LiDARbased trajectory and point cloud as the geometric backbone and allowing splats to provide texture, depth cues and realism.

This hybrid approach anchors the splats to a reliable frame of reference and that alignment is then used to extract geometry back out again. Revit plug-ins now exist that convert regions of a splat scene into architectural elements when the system believes it has identified a planar wall, an opening or a slab edge. In this mode, Gaussian splatting becomes less a visual trick and more an intermediate representation for automated modelling.

At the moment, site work is where splatting feels most compelling. It gives teams a way to record conditions more frequently, with far less planning, and with a visual fidelity that helps non-technical stakeholders understand what they’re seeing. In a world where disputes, RFIs and coordination meetings increasingly rely on photographic evidence, splats offer a richer form of ‘being there’.

3DGS developers The commercial ecosystem around Gaussian splatting is expanding quickly, particularly on the fringes of AEC, where fast capture matters more than survey grade fidelity.

Gauzilla Pro is one of the first platforms to position splats explicitly for construction. It reconstructs scenes directly from phone or drone footage, runs entirely in the browser and supports timebased playback so project teams can watch a site evolve. Some contractors are already using it to supplement drone surveys, creating 4D snapshots throughout a build that sit comfortably alongside BIM in coordination reviews. The founder of Gauzilla Pro, Yoshiharu Sato, spoke at NXT BLD this year. He also took part in a panel session on reality capture.

XGRIDS takes a more engineering-driven approach, combining SLAM capture hardware with Gaussian reconstruction and feeding it all into its Revit extension. By leaning on LiDAR to establish absolute accuracy and then layering splats for texture and machine learning, the system claims significant productivity gains in scan-to-BIM modelling. The splats, in this case, are less a deliverable and more a substrate for teaching AI what the built environment looks like.

Autodesk is now adding 3D Gaussian splatting into its infrastructure toolchain, signalling yet another shift in how the company wants customers to handle mobile reality-capture data. Instead of treating SLAMLiDAR scans and photogrammetry as external artefacts to be cleaned and imported, Autodesk’s pitch is that handheld captures will feed straight into its ecosystem, including tools such as ReCap, Civil 3D, InfraWorks, Revit, and Autodesk Construction Cloud, where they’re subsequently converted into lightweight splatbased models for project review.

Bentley Systems has also moved early on Gaussian splatting, adding support within its iTwin Capture ecosystem. This is significant, because Bentley’s reality-capture tools have historically centred on photogrammetry, meshing and high-fidelity point clouds, all of which feed into its digital-twin workflows.

By incorporating splat-based scenes, iTwin Capture can now handle radiance field style reconstructions alongside traditional survey outputs. Bentley positions this as a complementary layer, rather than a replacement. Splats provide rapid, photorealistic context from lightweight video capture, while the established photogrammetry and LiDAR pipelines remain responsible for geometry and measurement.

ESRI ArcGIS Reality has also joined in the splatting fun, albeit from the geospatial rather than construction-tech end of the spectrum. ESRI’s focus remains firmly on survey-grade photogrammetry, aerial LiDAR and large-area GIS datasets, but its recent support for radiance-field style reconstructions is a sign of its advantages.

ArcGIS Reality can now ingest splatbased scenes from drone or mobile imagery as contextual layers within broader reality models, using them to provide visual richness in areas where traditional meshes struggle, such as façades with shiny surfaces, dense foliage or cluttered streetscapes. Crucially, Esri treats splats as a complement to its established photogrammetric pipeline, not a replacement. The geometry still comes from calibrated aerial capture, while splats provide the rapid, lightweight visual context needed for field verification, planning and communication.

Pix4D has also been quick to bring Gaussian splatting into its ecosystem, as an appearance layer that sits alongside its established mesh and point-cloud pipelines. PIX4Dcatch and PIX4Dcloud can now generate splat-based scenes directly from mobile or drone imagery. Crucially, Pix4D anchors these splats in the same georeferenced frameworks it uses for survey-grade deliverables, so while the splats themselves remain a radiance-field representation, they carry proper scale and alignment back to site control.

On the consumer side, Niantic’s Scaniverse app has quietly normalised splat-based capture for millions of users. It can generate splats directly on a smartphone and has helped push an emerging splat file format into the wild. The significance for AEC is not the app itself, but the cultural shift it signals. Splat scenes are becoming a common currency and many people arriving to work on construction sites will already know how to produce them.

Rendering platforms are also absorbing splats. For example, Chaos has added support for 3DGS in V-Ray and Corona, allowing designers to light and render splat-based environments as part of a conventional workflow.

All of this activity points to a reality in which splats become a routine part of how we capture and communicate project conditions, even if they never ascend to the level of a contractual deliverable.

Hungry for change

Gaussian splatting arrives in the AEC industry at an interesting moment in time. The industry is hungry for faster, more frequent, less painful forms of capture. At the same time, firms cannot afford to lose the accuracy that comes from proper survey methods. Splatting sits between these two impulses: visually rich, operationally lightweight, but not yet ready to stand alone as a basis for engineering decisions.

The best way to position splatting, then, is as a new tier in the reality capture stack. At the base, we still have physical measurement: total stations, GNSS, LiDAR and SLAM. Above that sit photogrammetry and traditional point clouds, producing geometry that can be sectioned and dimensioned. Splatting represents a new layer on top, a fast and expressive way to capture radiance and appearance from video. Anchored to survey data, it becomes a powerful tool for documentation, communication and early-stage modelling. Teamed with AI, it may become a foundation for the next generation of automated BIM authoring.

There are still many unanswered questions here, of course. Splatting file formats are fragmenting before we hope they consolidate. Long-term archiving is untested. Interoperability is uneven. And no contract yet defines what a splat scene represents in legal terms. But the momentum is unmistakable and there are plans to make it an open standard.

In the short term, splatting will make site capture more fluid and more frequent and help teams reason about space in ways that flat imagery never can. Long-term, the more interesting prospect is not whether splats replace existing techniques, as accuracy improves and radiance-field representations become first-class citizens in design environments. If the industry starts modelling against splat-based realities – rather than merely viewing them – then Gaussian splatting will have done way more than just produce pretty pictures.

For now, the pragmatic approach is simple: Use splatting where it shines and treat it as one more instrument in the continually expanding orchestra of reality capture.

Splatting versus photogrammetry

While it may be tempting to position splatting as the successor to photogrammetry, the two approaches were built for different purposes. Photogrammetry has always been about recovering geometry. It solves camera poses, triangulates features, produces a point cloud, and from that, generates a surface that can be meshed, measured and exported. When handled carefully, the resulting model can support engineering decisions.

Gaussian splatting begins from the same camera solution but takes a different path. Rather than building a mesh, it uses the calibrated images to guide the optimisation of millions of Gaussians. The output is a radiance field rather than a surface. You can measure within it if you understand the camera geometry and if the training was anchored to reliable scale, but it is not inherently metric in the way surveyors would like.

It has its strengths, of course. Splatting handles reflections, specular materials, foliage and fine grained detail in a way that would cripple most photogrammetric pipelines. It avoids broken topology and jagged edges. It renders in real time, which makes it excellent for VR, walkthroughs and design reviews.

But it has weaknesses, too. Without a mesh, there is no clean way to extract a watertight object or generate a traditional deliverable. Metric reliability depends entirely on the underlying reconstruction. And unlike photogrammetry, splats do not solve occlusion with extra geometry; they simply approximate what the cameras saw.

The healthiest way to view splatting and photogrammetry is as complementary technologies. Photogrammetry remains the tool of choice for robust geometry and traditional deliverables. Gaussian splatting excels at producing high quality appearance data that can augment, rather than replace, geometric reconstruction.

Splatting versus laser scanning

Laser scanning lies at the opposite end of the spectrum from splatting: it’s a hard, physical measurement. A laser scanner records precise distances by timing the return of a pulse or analysing its phase. Registered correctly, the resulting point cloud is anchored to reality with an honesty that image-only methods cannot match. Surveyors trust it because the physics is transparent.

Gaussian splatting, by contrast, sits firmly in the realm of inference. It interprets imagery. With the right constraints, it can be aligned, scaled and registered, but it does not inherently know anything about distance. That is why hybrid workflows are emerging as the most sensible configurations for professional use, with SLAM or LiDAR for the backbone, and splats for the appearance.

In field conditions, splatting does offer practical advantages. Capturing a dense interior with photogrammetry can be time-consuming, and laser scanning demands careful placement and registration. By contrast, splat capture can often be performed in a matter of minutes. Several teams report cutting capture times dramatically by using a fast LiDAR sweep to establish structure and then letting splats fill in all the visual nuance. For messy, congested or partially complete sites, that speed may be the difference between capturing reality today or missing it entirely.

Accuracy claims should be viewed cautiously, however. When vendors refer to ‘survey-grade’ splat models, they are invariably referring to workflows where LiDAR or SLAM has done the geometric heavy lifting. Splats inherit that accuracy, they do not generate it. The Gaussian representation then serves as a high quality façade over a more traditional dataset.