Your brief is Mars: what would you design, construct or engineer for a new smart city in the Mars Valley, home to one million humans? Tanya Weaver reports on a new global competition that is asking participants to take their imaginations to infinity and beyond

It is 2117 and you’re standing on the side of a hill, looking down onto your city and its one million residents. The sun is setting and Earth is just a distant star. You’re on Mars, colonised by humans just a few decades ago.

As you stand there, are you breathing normally or inside a mask? Are you wearing a spacesuit or is your skin exposed? Is your home above or below ground? How do you move from place to place? What food do you eat and how do you grow it? What do you do for fun?

These are all tantalising questions – and they’re questions that the Washington-based National Space Society (NSS) is keen to see answered. The organisation’s vision, after all, is to see people and working in thriving communities beyond Earth. “I grew up under the stars in the Canadian prairies and developed a passion for space,” says director Chantelle Baier.

“The prospect of human exploration really excites me. We get to start thinking about what our houses will look like in space, what we’ll be wearing and what technologies will make living in space more comfortable.”

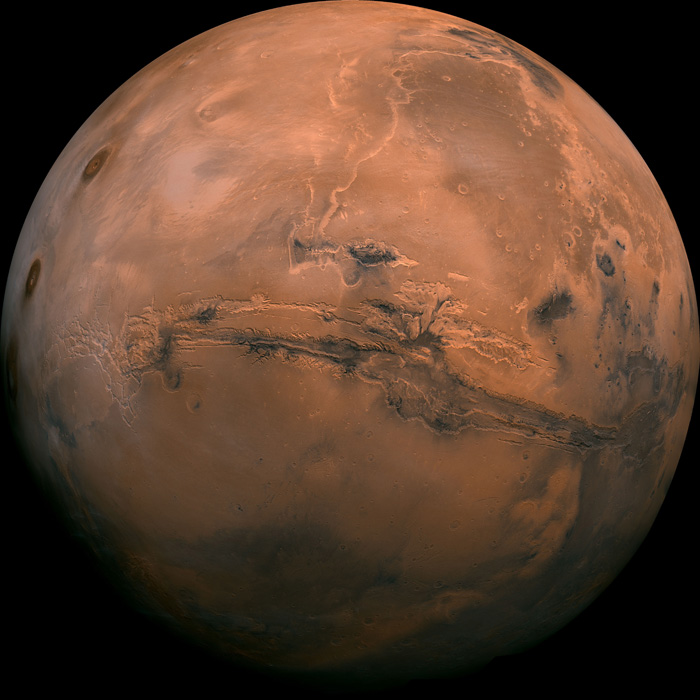

Race to the Red Planet

It is no longer a question of whether humans will get to Mars, but how soon. The race to the Red Planet has begun and several organisations are competing to win.

There is, of course, NASA, with its plan for humans to set foot on Martian soil by the end of 2030s.

Then there is California-based SpaceX, which also plans to boldly go where no human has gone before. Its founder, enigmatic entrepreneur Elon Musk, has revealed that SpaceX will begin manned flights to Mars by 2026 in a mammoth spacecraft that can take 100 people on each trip.

Dutch company Mars One, meanwhile, proposes to send 24 people to Mars by 2035. The number is precise: potential participants are being carefully vetted, since they will be required to dedicate their lives to the mission. It’s a one-way trip and the intention is for them to become Mars’ first permanent residents.

Long-term prospects Getting to Mars is one thing. Surviving on the planet is another thing entirely. From data so far received from Mars rovers, it’s not exactly a hospitable or desirable environment in which to live, especially if you’re one of the Mars One crew who will live out the rest of your days there.

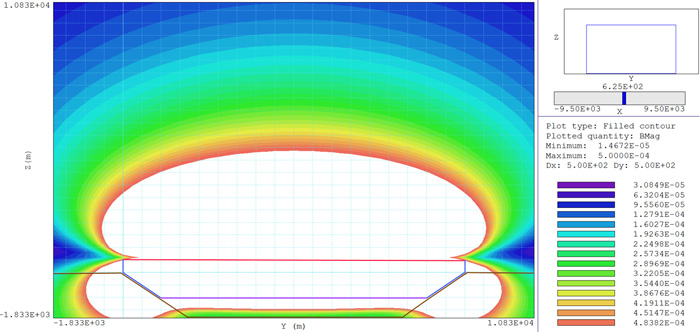

The planet’s atmosphere contains almost no oxygen. It is subject to intense radiation. Its seasons are extreme, with maximum temperatures in winter reaching -126C and in summer reaching a balmy 20C (the average temperature is -63C unlike earth’s 14C).

Mars is prone to massive dust storms and has 62.5% less gravity than Earth. On the positive side, it’s good for weight loss – if you weigh 100 pounds on Earth, you’d only weigh 38 pound on Mars.

Bearing all this in mind, why design for Mars? Why dedicate time and resources to creating technology for an inhospitable planet, when we have enough going on in our own planet, which could soon become pretty inhospitable itself, if we aren’t careful?

The reasoning offered by NASA and others is that technologies created for space can often be used here on Earth. In fact, NASA has a whole section of its website dedicated to technology transfer projects and spin-off companies based on that proposition.

For instance, Houston-based architect Garrett Finney was tasked by NASA to create space-saving designs for a ‘habitation module’. Inspired by this work, he then went on to set up Cricket (now known as TAXA Outdoors), a camper trailer company renowned for its compact, yet comfortable, ergonomic products.

Then there are water filtration systems, structural analysis software in the form of Nastran, and even a CO2 recovery technology system created for Mars that is being used by small-scale brewers to put the bubbles into craft beer.

Fuelling the imagination

The prospect of designing for another planet, no matter how inhospitable, helps fuel the imagination. It’s inspiring – not just for adults, but for children too.

As Mars One CEO Bas Lansdorp recently said at the Institution of Engineering and Technology’s (IET) Festival of Engineering event in London,

“I think landing on Mars will change our planet. It will inspire children to want to be engineers and scientists and astronauts again, instead of pop stars.”

But from Chantelle Baier’s point of view, the human-centric aspect of designing for Mars and space is paramount. Just because we’re leaving home behind, doesn’t mean that our destination shouldn’t be comfortable and aesthetically pleasing.

“The emphasis on designing for space is predominantly focused on engineering and functionality. Right now, the International Space Station looks like a tin can – it doesn’t look warm and homely,” says Baier, whose background, interestingly, lies in the diverse fields of geology and fashion design.

“It’s about the importance of beauty and design that surrounds us on Earth and how we can implement this when planning our Mars colonisation,” she adds.

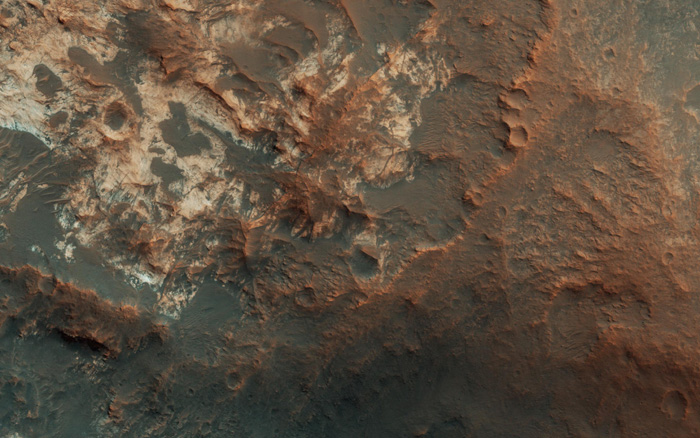

Baier is bringing these views to a new competition – HP Mars Home Planet – for which she sits on the advisory panel. Organised by HP and Nvidia, this yearlong competition, launched in August 2017, is a challenge to the creative community to design solutions for a time when there are one million people living on Mars. More specifically, the challenge envisages they’ll be living in Mawrth Vallis – Mars Valley in Welsh – already identified by NASA as a potential landing site.

“We’re not trying to figure out why a million people are on Mars, we are just accepting that they are there and living a happy life,” says Sean Young, HP’s worldwide segment manager for product development and AEC, who is managing the competition. “This implies a number of innovations in technology and we wanted to tap into the talent and capability among architects, engineers, civil engineers and designers to really reinvent life on another planet,” he adds.

Blank sheet design brief

In a sense, this is the ultimate ‘blank sheet design brief’, because Mars is literally empty. Of course, there are considerations and limitations in terms of climate, soil and atmosphere, but you could literally let your imagination run riot in creating solutions for a Martian smart city.

Frustrations on our current planet could be solved for another. Participants have the opportunity to completely rethink how humans can survive and thrive. Their mission: to think outside of the box or, more to the point, to think outside the planet.

As Baier says: “With Mars having onethird gravity of Earth and very, very low pressure, things that aren’t safe in one planet might be safe in another. Perhaps you can design higher buildings that won’t topple over.”

The Mars Home Planet competition, unlike its predecessor, Project Soane, which was targeted predominantly at architects, will be relevant to all HP’s customers, including students. “The key thing is that they are using the tools they use daily, such as Revit, Maya, Fusion 360 and 3d Max, and so for that reason, we partnered with Autodesk,” says Young.

The competition consists of three phases: concept (now complete); 3D modelling; and rendering. Each phase doesn’t lead on from the previous one – it’s not a question of asking entrants to follow a design through from concept to rendering. Instead, each phase is independent, with its own deadline and prizes.

“The idea with the concept phase was to create a low barrier for entry: anyone can get involved as they don’t need to use a 3D application. The aim was to get the word out there and to inspire the next phase,” Young explains.

“We received over 470 entries and we were truly blown away by them. They ranged from basic schematics to detailed architectural concepts and even some that looked like full on thesis papers,” he laughs.

With help from the advisory panel, which includes individuals representing space, design, architecture, science and virtual reality, among others fields, the entries were whittled down into a shortlist.

These were then presented to a preeminent panel of judges, including Dr Robert Zubrin, president of the Mars Society; Daniel Libeskind, architect and founder of Studio Libeskind; Chris deFaria, president of DreamWorks Animation Group; and Andrew Anagnost, CEO of Autodesk.

The winners were announced at the recent Autodesk University Las Vegas 2017. Among them were Jesus Velazco from Venezuela, who received the award in the architecture category for ‘Solar Powered Colony’, which features a main structure underground with only a solar farm above ground.

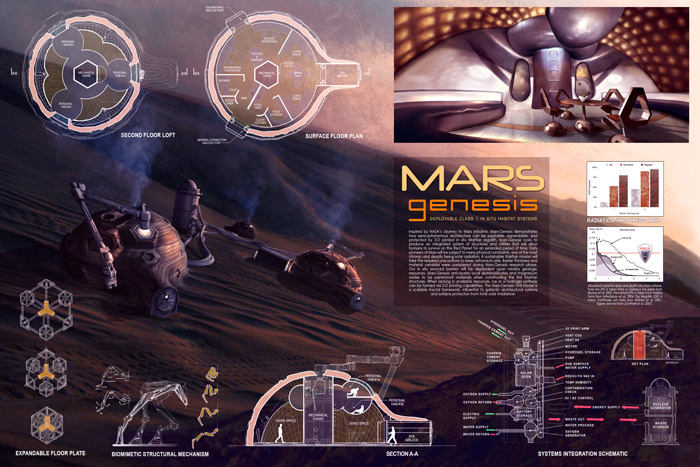

Kenny Levick from the US received the Infrastructure award for ‘Mars-Genesis & Mawrth-Integra: Interplanetary Design’, which focuses on how semi-autonomous architecture and the construction of an early colonisation infrastructure network can aid in the growth of humans on Mars.

Xavier Albizu of Spain received the transportation award for his ‘MARS Multi Utility Vehicle’ and Jorge Moreno Fierro of Columbia received the design award for his adaptive parametric construction machine called ‘Bio System’.

Mars Home Planet Urbanisation Concept Challenge

Second phase launched

At Autodesk University this month, the second, 3D modelling phase of the competition was launched. The deadline for entries is 25 February 2018.

For this phase, participants need to create 3D models of their designs in categories including civil engineering, architecture, industrial design, vehicle design, mechanical engineering, 3D art and interior design. As Young says, “The rules are: respect the physics of Mars, use your imagination and have fun!”

Asking Baier of NCC what her advice to entrants of this phase would be, she says, “Design your base for people to have things to do. I suggest science and entertainment. Don’t design a Mars base like an Apollo spaceship that ignores human factors. Take into account that people need space. You want people to be happy and healthy.”

Launch Forth

Although the competition consists of these three phases, there are a whole range of other activities to get involved in at the Mars Home Planet competition website. This is being managed by Launch Forth, a software-asa- service (SaaS) platform for product design.

Participants are encouraged not just to log in to submit their entry and log out again, but also to join the site’s community to brainstorm, comment, give feedback and collaborate around other non-challenge categories such as lifestyle, farming and robotics. There is even a leaderboard to track progress and to see how you stack up against others in the community.

“Launch Forth is a tried-and-tested cocreation platform from Local Motors that uses open innovation to accelerate the product development process. And for Mars Home Planet, they have created a whole Mars community based on this platform and already 35,000 have signed up,” explains Young.

The competition accepts entries from both individuals and teams. A virtual team could even be set up amongst community members on the platform. “For example, if you’re an architect and you need some chemical engineering help, or you need somebody that really knows about the science of Mars, you could invite them to partner up and join your team,” he adds.

Baier considers this a real advantage, as it means entrants aren’t working in silos. “You get conversations started and that helps stimulate your imagination. I think that scientists like that, too, because they are so used to thinking about things like jet propulsion that they are often not allowing themselves to think creatively,” she says.

There is also a virtual reality (VR) element to the competition, running in parallel with these three phases. Using Mars Valley terrain from Fusion’s ‘Mars 2030’ VR game, based on real NASA-supplied terrain data and imagery, special effects company Technicolor will help co-creators on the Launch Forth platform to bring the winning entries into the Unreal Engine.

The end result will be a VR simulation of a smart city in the Mars Valley, created through the combined imagination of Mars Home Planet contributors.

This crowdsourced VR experience will be revealed when the year-long competition draws to a close at Siggraph in August 2018. Here, event visitors will be able to strap on an HTC Vive headset and imagine themselves as one of the one million people experiencing life on Mars.

Young is looking forward to the upcoming phases of the competition. “The competition is basically a petri dish for imagining the best possible utopian society and how this one million martians will be living in this built environment. And who knows where it could lead? We could even see these designs being used in Mars in the future.”

■ launchforth.io/hpmars

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to AEC Magazine for FREE